To the people of Connecticut

From Richard Gimbel’s pamphlet New Political Writings by Thomas Paine. However:

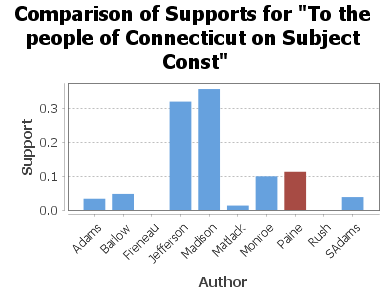

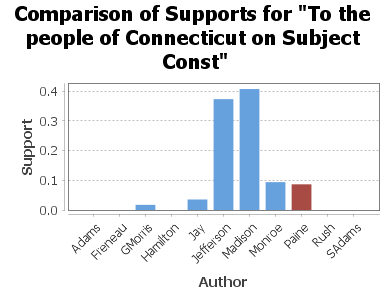

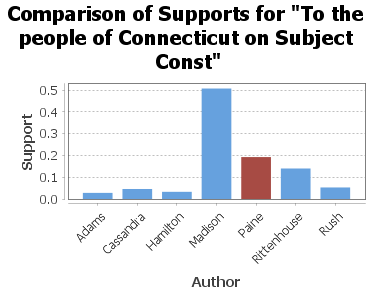

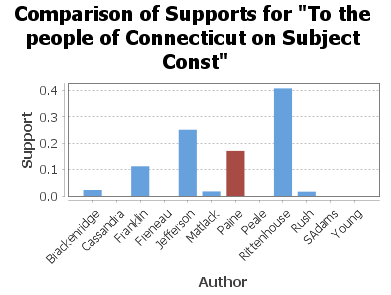

In a letter to the American Mercury on Aug 27, 1804 Paine says: “I have received three of your papers. The first wherein you announce for publication of the piece I sent to Mr. Bishop signed A Friend to Constitutional Order [THIS ARTICLE]. The next, in which the piece is published; and the last (August. 23).” However this piece does not test as Paine’s. Paine also claims 2 weeks later about CT politics “It is always of use to know the ground an enemy occupies. I have sometimes a leisure hour in which I might give a little auxiliary aid, but I am not enough informed of what is going on to do it.” So this is a dilemma. The testing methodology is very accurate. The piece could have been written by someone more knowledgeable of Connecticut politics, as Paine spent several weeks in Connecticut before going to New Rochelle. He was still there in mid-August. This piece appeared on Aug 2nd. His discussions with Republicans there could have spurred someone there to write the piece. Subsequently when the NUMA series began in October (not yet republished), his first contributions had to be corrected by the editor for lack of local history knowledge. Paine submitted two articles in August, on the 16th and 30th, which dealt with answering Federalist spokesmen and making fun of their absurdities, which were not as organized as this piece. Here are representative tests:

For the MERCURY To the people of Connecticut, ON THE SUBJECT OF A CONSTITUTION

IT was not generally known, until Mr. Bishop’s excellent Oration of last May appeared, that the State of Connecticut had not a Constitution. Congress some time in 1775 or the beginning of ’76 recommended to the people of the several provinces (as they were then called) to take up and establish new governments; but the Legislature of Connecticut, disregarding this recommendation of Congress, assumed the power of enacting that the form of government contained in the Charter of Charles the 2d of England, should be the civil constitution of Connecticut.-This was an unwarrantable act of assumption of the legislature of that day. The right of forming a Constitution belongs to the people in their original character, and cannot be exercised by any body of representatives unless they are chosen expressly for the purpose.

The people of Connecticut have now to exercise the right they ought to have exercised before, for it may be doubted, whether in their present condition, not having an authorised Constitution, they have any legal government of their own. The Legislature which enacted that the form of government contained in the Charter of Charles the second should be the civil Constitution of the state could not derive the right of so doing from the Charter itself, because the Charter could not give the right of changing the authority from whence it issued and under which that legislature was then sitting. The only source from whence such a right could proceed was the authority of the people, but this the legislature was not possessed of because they were not invested with it, nor elected, as Conventions in other States were, for the express purpose of forming a Constitution. The act therefore which changed the name of Charter into that of Constitution being an unauthorised act, is in itself a nullity.

Neither have the present legislature any right in the matter otherwise than as individual citizens, because the right of forming and establishing Constitutions belongs, as before said, to the people in their original character, and cannot be assumed or exercised by any body of men elected for the ordinary purposes of legislation.

It is evident, from the nature of the case, that the first step towards bringing this business forward must be voluntary, for in all cases where rights are equal, though any one may propose or recommend, none can have authority to command in the first instance.

Let then, in the first place, the people of the several towns elect Town Committees, and let the elections be made by persons subject to military or militia duty or who pay taxes.

Secondly, Let the Committees thus elected be authorised to appoint deputies to meet in conference with deputies from the other towns.

Thirdly, Let the deputies thus met in conference form a plan for the election of a Convention, which shall be authorised to form and propose a Constitution to the people.

Fourthly, When the Constitution is proposed let it be voted for by YEAS and NAYS by all the people of the several towns who were entitled to vote for the Town Committees in the first instance.

It is not difficult to foresee that when the Constitution shall be before the people for their consideration, there will be those who will be proposing alterations or amendments, some will do this from a good motive, and others from no other motive than that of embarrassing and preventing the matter coming to a conclusion, like the Connecticut members in Congress to prevent the repeal of the internal taxes.

As a Constitution should contain within itself the means of amending any part thereof as time and experience shall shew necessary, and as it is to be presumed the Convention will discuss every article they adopt, more effectually than men thinking individually can do, it will be best to vote its adoption or rejection simply by YEAS and NAYS, unincumbered by conditions. There has been so much experience on the principles and manner of forming Constitutions since the revolution began, that no material error can now take place. This was not the case at first. The legislature that assumed the power of re-enacting the Charter knew so little about Constitutions that they arrogated to themselves the right of establishing their illegitimate of spring through all generations. There is no article which provides for the amendment. They dethroned Charles and then put themselves in his place, and to display their sovereignty they uncharted the charter to charter it anew. The whole matter therefore must now begin as it ought to have began at first, on the authority of the people in their original character.

Governor Trumbull, in his speech to the Legislature in May last, informed them of the proposed amendment to the Constitution of the United States, by designating the persons to be voted for as President and Vice-President, and he made this the occasion of speaking against the policy of altering Constitutions on “SPECULATION.” This word was very injudiciously applied to the case; be cause it is not on SPECULATION but on EXPERIENCE had at the last Presidential election that the amendment was proposed. Something, therefore, must have been in Governor Trumbull’s mind, besides the case itself, to have led him so far and so erroneously from the merits of it. He could not but know that Connecticut, though it has a form of government, has not a Constitution, and that the thing patched up in the place of one (and that by those who had not authority for the purpose) has no declaration of rights prefixed to it, nor any article in which it provides for its amendment. It was therefore consistent with the policy of the party to which Governor Trumbull adheres, to keep all considerations on the subject of Constitutions and amendments as distant as possible from the minds of the people. It might occur to that party, that if we (the Feds) agree to amend the Constitution of the Union, it will suggest the idea of looking into our own, and in that case, the firm of MOSES and AARON, and the beast with SEVEN HEADS*, will fall like the dagon of the Philistines.

A Friend to Constitutional Order.