By Michael J. Williams

Part 1

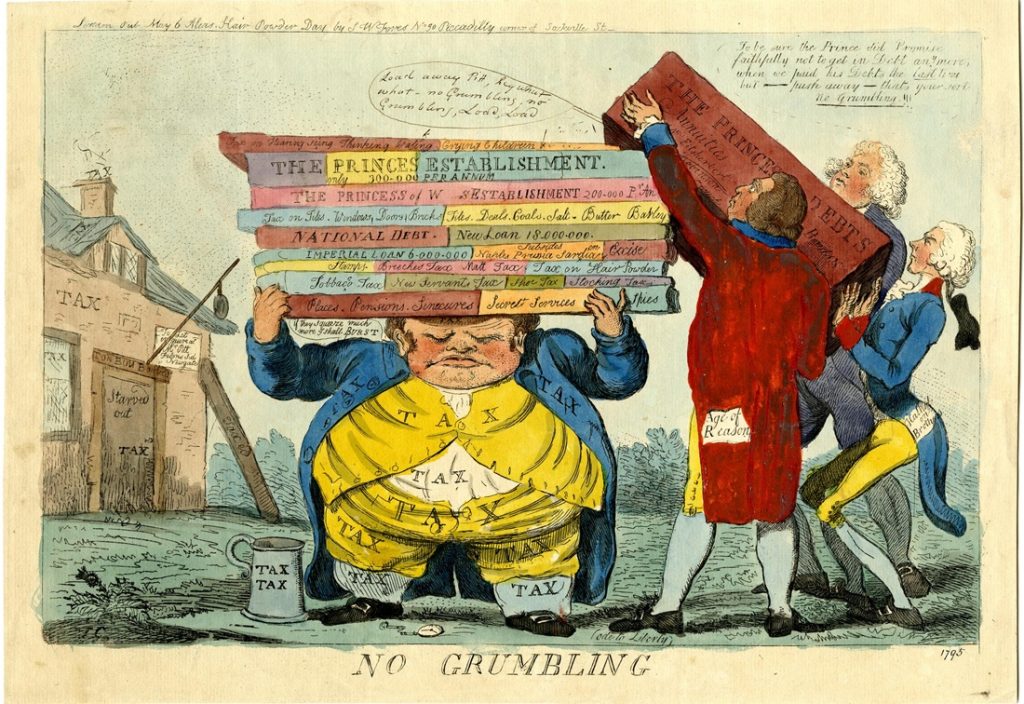

DESPITE VARIOUS CONFLICTING interpretations, there is general agreement that a significant extension of the political nation was one of the fundamental aspects of British social development during the 1790’s. According to J.I. Western, whereas prior to the 1790’s governmental stability depended upon a broad apathy and indifference toward the national political process among the lower orders faced with the threat of major social upheaval agents of Pitt’s government were responsible for the creation of a broad conservative consciousness among the bulk of the propertied classes. (J. Western. ‘The Volunteer Movement as an anti-revolutionary Force’. E.H.R. (1956).1) 0603-5, 6133 cf. A. Mitchell, ‘The Association Movement of 1792-3’. Hist. J1. (1961) .p.57.) During this decade the poor began to be looked upon from totally different aspects. ‘The shock of the French Revolution had brought with it a new way of looking at the mass of the nation’. Previously the poor had merely rioted; they had rebelled only upon the instigation of members of the ruling class. ‘After the French Revolution the tone was very different. The poorer classes no longer seemed a ‘passive’ power, they were dreaded as a Leviathan that was fast learning his strength. Or we may say that before they were regarded as people morally content, they were now regarded as people naturally-discontented.’ (J. L. & B. Hammond. The Town Labourer 1760-1832. (liongmans,1920). p.93-4.) Such a relatively novel fear of social revolution, absent since the Mid-seventeenth century believed to draw the propertied together as a class. (H.J. Perkin. The Origins of Modern English Society. (R.K.P.,1969). p.195) Those historians who have chosen as their subject the emergence of the working class movement have adopted a similar view of the period. E.P. Thompson has argued that the 1790’s witnessed for the first time the ‘emergence of a national and international consciousness among significant numbers of working men.’ According to Gwyn Williams, 1792 saw the entry of a new breed of men’ into the political arena. (G.A. Williams. Artisans and Sans-Culottes. (Arnold, 1968). p.66.)

Anxiety concerning this downward extension of the political nation was responsible for the prosecution of radical pamphlets in the 1790’s. In 1793 Daniel Holt of Newark was prosecuted for publishing a pamphlet previously issued with impunity by the Westminster Committee. The only reason for this was his re-addressing it to ‘tradesmen, mechanics and labourers.’ (State Trials, xxii. p.1201,1237.) Paine’s Rights of Man was prosecuted for libel not so much because of its contents but because, rather than confining his audience to ‘the judicious reader’, he had addressed ‘the lowest orders of the people – people who…cannot from their education or situation in ‘life, be supposed to understand the subject on which he writes.’ (Ibid., p.381, 780.) The prosecution in 1794 of Eaton’s Politics for the People stemmed precisely from the intended audience indicated by title, tone and price. The case for Eaton’s defence on the other hand rested upon the right’of access to political information on the part of the whole of the people. (Ibid., xxiii. p.1019, 1023, 1027, 1034.)

It is clear that both conservatives and radicals ascribed to pamphleteers and booksellers a central role in this struggle over the extension of the political nation. (Cf. Thompson. p.118.) The massive number of tracts published by Reeves’s Loyal Association and under the Cheap Repository imprint were both the conservative reaction to Paine, and a recognition of the irreversibility of that extension of the political nation which he, more than.any other individual had accomplished. Philip Brown observed that, ‘Bookselling and publishing began to touch a new public. A new specialist in the trade, the “Political Bookseller”, began to’advertise himself. (P.A. Brown. The French Revolution in English History. (Cass, 1918). p.71.) Thompson commented upon the central place within Sheffield that Jacobinism occupied by Joseph Gale’s journal bookshop and pamphlet press. (Thompson. p.166r.) The main targets for persecution on the part of the local Loyal Associations were apparently booksellers. (Mitchell. p.69.) The principal agency then in this downwards extension of the political nation was the radical bookseller.

Hostile contemporary observers from Burke onwards emphasised the connection between political radicalism and infidelity. It seems to have been Burke who, in his vastly influential Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790), initially established this connection, regarding the events in France as ‘this philosophic revolution.’ (E. Burke. Reflections on the Revolution in France. (Penguin, 1968). p.237.) ‘Licentious philosophy’ and ‘insolent irreligion’ had been the ruin of the French monarchy. (Ibid. p.244, 125.) The Revolution itself he ascribed to the conspiratorial machinations of a cabal of so-called philosophers, ‘whom the vulgar, in their blunt, homely style commonly call Atheists and Infidels. (Ibid. p.185-6.) The Revolution’s excesses he ascribed to savagery engendered by widespread diffusion of ‘the spirit of atheistical fanaticism. (Ibid. p.262.) The subsequent course of the French Revolution, especially in its Jacobin phase, apparently justified Burke’s analysis and prediction of a full-scale attempt to extirpate Christianity. (Ibid. p.256.) The widely read and profusely documented works of Barruel and Robison (1798) reinforced the view of the Revolution as the first manifestation of an international conspiracy aiming at the overthrow of all governments and the extinction of Christianity. (A Barruel. Memoirs pour servir a l’histoire du Jacobinisme; J,Robison. Proofs of a Conspiracy against all the Religions’and Governments of Europe. The latter went through five editions in two years.R.A.Soloway. Prelates and People. (R.K.P.,1969). p.36n.)

To ascribe the French Revolution as an atheistical conspiracy, its political excesses to divine anger at that country’s moral and religious apostasy, became the contemporary conventional wisdom among Conservative Englishmen. (See Soloway, Chapter 1. M.J.Quinlan, Victorian Prelude. (ff.Y.1 1941), chapter III. V. Kiernan .’Evangelicalism and the French Revolution’, Past and Present,1952.) An anonymous contributor to The Gentleman’s Magazine of 1797 succinctly expressed the prevalent attitude; ‘Whatever proximate circumstances hastened the Revolution in a neighbouring state, infidelity was its prime cause; and the vengeance of an offended God has been awfully manifested. (The Gentleman’s Magazine. LXVII .(i).1797. p.188.) In his Apology for the Bible (1796), Bishop Watson spoke of that evil heart of unbelief, which brought ruin on a neighbouring nation. (R. Watson & Autology for the Bible. (London,1797). P.384.) For Wilberforce, the Revolution was an awful warning of the consequences of infidelity. (Wilberforce. A Practical View of the Prevailing Religious System, etc. (London, 1797) 13 101398.) Ipadman, another critic of Paine, identified the French Revelation with Deism, its horror being the expression of irreligion and impiety. (I. Padman. A Layman’s Protest assinst… Thomas Paine. (1797). p.190-1.) The famous liberal Baptist divine, Robert Hall, saw the barbarities of the Revolution as justly chargeable on the prevalence of atheism. Let those who doubt of this recollect that the men who, by their activity and talents, prepared the minds of the people for that. great change Voltaire, D’Alembert, Diderot, Rousseau and others, were avowed enemies of revelation; that in all their writings the diffusion of scepticism and revolutionary opinions went hand in hand, that the reign of atheism was avowedly and expressedly the reign of terror.

As the heathens fabled that Minerva issued full-armed from the head of Jupiter, so no sooner were the speculations of atheistical philosophy matured, than they gave birth to a ferocity which converted the most polished people in Europe into a horde of assassins. (R. Hall. ‘Modern Infidelity Considered with Respect to its Influence on Society’ (1799). In Works. (7th. Edition, 1841). i.p.46-7.)

Not only did the extension of the political nation arouse considerable anxiety among the propertied classes, but also the observation that associated with ‘political radicalism’, the theological radicalism of infidelity was also penetrating the masses. Indeed their attitude towards contemporary French events predisposed them to make such a connection. By the close of the decade it was no longer felt possible to echo Burke’s complacent assertion of 1790 ‘that there is no rust of superstition’ that ninety-nine in a hundred of the people of England would not prefer to impiety.’ (Burke.p.187.) A new proselytising zeal among lower-class infidels was the source of such anxiety, particularly in the light of what we have seen to be the standard conservative interpretation of the origin of the French Revolution. Gibbon, the most notorious of the late eighteenth century aristocratic sceptics, was prepared to forgive Burke’s superstition in the light of its trenchant criticism of democratic principles. Terrified by the course of the French Revolution and its destruction of his personal ease he, seemingly with seriousness, argued in favour of the Inquisition.’ Referring to the possibility of any extension of his own infidelity to the masses, he wrote:

I have sometimes thought of writing a dialogue of the dead, in which Lucian, Erasmus, and Voltaire should mutually acknowledge the danger of exposing an old superstition to the contempt of the blind and fanatic multitude.” (E. Gibbon. Autobiography. (0.U.P0,1907). 13.249,262,216.)

Robert Hall drew attention to:

The efforts of infidels to diffuse the principles of infidelity among the common people… HUME, BOLINGBROKE, and GIBBON, addressed themselves solely to the more polished classes of the community, and would have thought their refined speculations debased by an attempt to enlist disciples from among the populace. Infidelity has lately grown condescending; having at length reached its full maturity, it boldly ventures to challenge the suffrage of the people, solicits the acquaintance of peasants and mechanics, and seeks to draw whole nations to its standards. (Hall .i.p 59,63.)

The parallel phenomena of the anti-Christian aspects of later phases of the French Revolution and Paine’s dual authorship of Rights of Man and The Age of Reason served to demonstrate conclusively the association of popular radicalism and popular infidelity.

The Englishmen of the upper and middle classes had already learned from French history to associate political radicalism with infidelity and now the development in England seemed only to prove an inalienable connection between the two. Such phrases as ‘infidel democracy’, ‘sedition and blasphemy’, etc., came almost unconsciously to be part of the intellectual equipment of these two classes. (H.A. Faulkner. Chartism and the Churches. (Columbia U.P., New York, 1916). P.16. of Quinlan .p.78. Brown. p.182.)

For Hannah More, ‘Republicanism and infidelity…are sworn friends both here and in France.’ (‘Will Chip’ (Hannah More). A Country Carpenter’s Confession of Faith. (1794). P.21.) ‘Churchman’, attacking Paine, wrote: ‘Republicanism and Deism, have the most intimate alliance in principle, and have seldom long been separated in practice… scepticism and political licentiousness, infidelity and contempt for the civil magistrate advanced with equal progression. (‘Churchman’. Christianity the Only True Theology or Answer to Paine’s Age of Reason.)

Paine’s writings were the principal literary agencies responsible for both the deliberate extension of a radical political consciousness and a comparable extension of infidelity to new sections of the population. Whereas hitherto the ‘rank weed’ of infidelity had been confined to ‘the great and opulent’, Bishop Watson accused Paine of ‘endeavouring to extend the malignity of its poison through all classes of the community. (Watson. p.382.) Robison, objecting to his popular tone, made a similar accusation. (Robison. p.479-80.) Hannah More, writing in early 1797 to Zachary Macaulay, considered ‘speculative infidelity, brought down to the pockets and capacities of the poor’, as a ‘new area in our history,’ which required ‘strong counteraction. (W.Roberts. Memoirs of the Life and Correspondence of Mrs.Hannah More. (Seeley, 1g34). ii.P.458.) As Reeves’s Loyal Association ‘was formed principally to counteract the influence of Rights of Man’, so in comparable fashion were the Cheap Repository Tracts issued to counter The Age of Reason. A comment in a letter from Hannah More to Wilberforce in 1796 upon Watson’s Apology clearly reveals the intent behind her tracts: ‘I could tell him with great truth that I much admired it; but I told him also, that a shilling Poison, like Paine’s, should not have a four shilling antidote. (Ibid. p.446. Cf. Quinlan. p.123.) P.Q. of Salisbury advocated cheap editions of Watson to counteract Paine’s work. (Gentleman’s Magazine. LXVI (i).1796. p.270.)

From the above evidence, it is clearly apparent that Paine is, in both religion and politics, one of the crucial figures of the 1790’s. His significance lies in his destruction of the symbolic universe of Christianity and Constitution, Church and King, in The Age of Reason and Rights of Man. Discussing the impact of infidelity in the 1790’s R.N. Stromberg writes:

Voltaire and Paine began to reach the English working classes…. about 1796…. This popular deism was not very important. Paine was effective through….Rights of Man, not The Age of Reason; if this extreme deist was to become the very ‘centre and life’ of the ‘radical’ political movement of the 1790’s, it was not because he attacked religion, but because he spoke out against political corruption and inequality. This English Radicalism paid relatively little attention to religion. (R.N. Stromberg. Religious Liberalism in Eighteenth-Century England. (0.U.P., 1954) .p164. This opinion is virtually repeated in the most recent article on The Age Of Reason, P.K. Prochaska„ ‘Thomas Paine’s The Age of Reason Revisited. J1. Hist. Ideas. 1972, passim.)

It should be apparent from the preceding pages, that such a separation of republicanism and infidelity is untenable, that in the minds of both radicals and conservatives, and especially among the latter, the two were inextricably fused. Perhaps it was in the interest of conservatives to emphasise, for purposes of propaganda, such an association. Retrospectively Southey considered that ‘the union between infidelity and sedition during the late war…. ruined the democratic party.’ (R. Southey. Letters from England (first published 1807; reprinted The Cresset Press,1951). p.400) From its inception, infidelity and republicanism were inextricably connected within British popular radicalism. (E.J. Hobbsbawn. Primitive Rebels. (Manchester U.P.*, 1959). p.128. E. Royle. 2 11 2211Al2.1121719211.22 adol.22.111 kaLIEL (Longman,1971. p.3.)

As a consequence of his pre-eminence in establishing such a connection, at least at an ideological level and within his own life, an examination of the writings of Thomas Paine, on both religious and political subjects, is essential. Although this part is concerned principally with Paine’s writings on religion, it would be wrong to consider them either in isolation from the political writings of which the bulk of his work consists’, or as a mere afterthought to these concerns. From his youth Paine was concerned with religion and in his declining years in New York State he was active primarily as a Deist. Politics were by no means his initial concern. A youthful interest in science preceded any political concerns:

The natural bent of my mind was to science… I had no disposition for politics. It presented to my mind no other idea than is contained in the word Jockeyship. When, therefore, I turned my thoughts upon matters of government, I had to form a system for myself that accorded with the moral and philosophic principles in which I had become educated. (T. Paine. The Age of Reason. (ffatts, 1938). P.39-40.)

The understanding of Paine’s intellectual background is dependent upon the interpretation of that final phrase. It was originally maintained by M.D. Conway, Paine’s first serious biographer, that these principles were primarily those goa Quakerism acquired by assimilation during his childhood in Thetford. (M.D. Conway. The Life of Thomas Paine. (Putnam, 1892). I.p. 4-51231; ii.p.182-220.) Such an interpretation has been rendered obsolete, largely as a consequence of the detailed researches of who has argued that Paine’s ideas on all subjects can be adequately explained only ‘when the organic development of the complete body of his thought is considered in relation to the pattern of ideas germane to the enlightenment, and, in particular„ to scientific deism, which as powerfully reinforced by Newtonian doctrines of natural law and order.” (H.H. Clark. ‘Toward a Reinterpretation of Thomas Paine’. American Lit., 1933. p.133-4. On the question of Paine’s relationship to Quakerism, see also, R.P.Faik. ‘Thomas Paine: Deist or Quaker?’ Pennsylvania, MaA. of Hist. and Biog, 1938. R.R. Fennessy. Burke, Paine and the, Rights of Man. A Difference of Political ougal (Martinus l Nijhoff, The Hague, 1963). p.12-14.)

The crucial influences upon Paine’s intellectual evolution were, argues Clark, the scientific lectures of those popularisers of Newtonianism, Benjamin Martin and James Ferguson, which ‘may have aided in moulding his scientific deism.’ (Clark.p.135.) Far from his political preceding his religious opinions,’ ‘his political theories grew out of his religion, his scientific deism, and its moral and political implications’, particularly his ‘Newtonian’ conception of the social harmony which would flow automatically upon the removal of traditional political impediments.’ (43. Ibid. p.136-9.)

As a believer in the applicability of scientific modes of thought and methods of investigation to all areas of existence, for Paine the essential task was to bring to bear the clarity of thought and simplicity of expression characteristic of science upon those regions where mystification had previously been dominant. It was upon the maintenance of such mystification that despotic power rested. Apropos the ‘science’ of government he wrote in 1795:

Notwithstanding the mystery with which the science of government has been enveloped; for the purpose of enslaving, plundering, and imposing upon mankind, it is all things the least mysterious and most easy to be understood. The meanest capacity cannot be at a loss, if it begins its enquiries at the right point. Every art and science has some point, or alphabet, at which the study of that art or science begins and by the assistance of which the progress is facilitated. The same method ought to be observed with respect to the science of government. (T. Paine. ‘An Essay on the First Principles of Government’ (1795). Edited by M.D. Conway. Collected Writings. (republished. Franklin, N.Y., 1969). iii. p.257.)

Paine’s writings are expressive of his belief in the decisiveness of an appeal to the innate rationality of his readers. In Common Sense he wrote:

In the following pages I offer nothing more than simple facts, plain arguments, and common sense: and have no other preliminaries to settle with the reader, than that he will divest himself of prejudice and prepossession, and suffer his reason and his feelings to determine for themselves: that he will put on, or rather that he will not put off, the true character of a man and generously enlarge his views beyond the present day. (Paine.’Common Sense’ (1776). Edited by W.M. Van der Weyde. Collected Works. (Thomas Paine National Historical Association, N.Y., 1925). ii.p.122-3.)

Paine was the enemy of all forms of ‘superstition’, be they political or religious. His possession in full measure of the characteristic contemporary faith in the power of reason and his experience during the American Revolution convinced him of the immense potential impact of the political pamphlet addressed directly to the masses. (If the American Revolution demonstrated to Paine the power of reason it also demonstrated its limitations. Advocating a people’s war against the German monarchies in 1792 he wrote reason with despots is throwing reason away. The best of arguments is a vigorous preparation.’ (Conway, C.W., iii. p.79).) In 1792, when sales of cheap editions of Rights of Man were claimed to exceed 30,000 monthly, Paine wrote apropos his impending promotion in absentia for seditious libel:

It will hereafter be placed in the history of extraordinary things, that a pamphlet produced by an individual unconnected with any sect or party,…that should completely frighten a whole Government, and that in the midst of its most triumphant security. Such a circumstance cannot fail to prove that either the pamphlet has irresistible powers, or the Government very extraordinary defects, or both. (Paine. ‘Address to the Addressers’ (1792). Cal., iii. p.58,55)

In the same pamphlet he remarked that, ‘Truth, whenever it can fully appear, is a thing naturally familiar to the mind, that an acquaintance commences at first sight’, and that ‘it is impossible to calculate the silent progress of opinion, and also impossible to govern a nation after it has changed its habits of thinking, by the craft or policy that it was governed by before.’ (Ibid. p.46,94) A decade later he considered that had conditions in England approximated to those existing in the Colonies in 1776, Rights of Man would have produced results similar to those effected by Common Sense. (Paine. ‘Letters to the Citizens of the United States’. C.W., iii. p.382.)

Paine’s faith in the power of reason, stemming both from personal experience and his scientific deism, in association with a democratic conception of politics as the concern of every man rather than the mysterious prerogative of a privileged minority, had certain definite stylistic consequences. (Cf. Fennessy. p.245. J.T. Boulton.The Language of Politics in the Age of Wilkes and Burke. (R.K.P., 1963). p.139.) The central characteristic of this style was what might be termed ‘the technique of demystification.’ The simplicity and clarity of scientific discourse, which had been presented as an ideal prose model by Bishop Sprat as early as the 1660’s, was opposed to the elaborate periods characteristic of the traditional literary manner.’ (T. Sprat. The History of the Royal Society of London. (1667). p.112-3.) As Clark observes, ‘the distinctive features of Paine’s theories of literary composition….were in no small measure conditioned by scientific deism.’ (Clark. p.144.) Just as the natural sciences were the enemies of superstition, in analogous fashion a prose modelled on scientific discourse was the appropriate instrument for the destruction of other forms of superstition. In Rights of Man his principal target was the political superstition of hereditary government. (Paine. Rights of Man. (Watts 1937). P.149.) ‘A superstitious reverence for ancient things maintains the ignorance upon which tyranny rests.’ (Ibid. p.172.) He condemned Burke’s “contemptible opinion of mankind” as a herd of beings that must be governed by fraud, effigy and show. (Ibid. p.147.) Men must be awakened from the dreams of superstition to a rational conception of their real interests. In contrast to Burke’s melodramatic mystification and complex prose, clarity, vigour and economy of expression were essential in effecting the destruction of the great enemies, prejudice and ignorance.’ (Ibid. p.147.)

It is precisely the recognition of the difficult necessity of breaking through the centuries old prejudices forming so firm a bulwark of traditional authority that accounts for the force and brutality of Paine’s style’. (Cf. ‘Common Sense’. C.W. (Weyde). Ii. p.93,102,106; Rights of Man. p.128; The Age of Reason. p.222.) Only by demonstrating clearly to men their real interests, can prejudice be destroyed. (Rights of Man. p.128,121.) As Thompson observes, many expressions in Rights of Man have ‘some of the dare-devil air of blasphemy. He was the first to dare to express himself will; such irreverence; and he destroyed with one book century-old taboos.’ (Thompson. p.100. Cf. Williams on Rights of Man ‘Most shattering is the tone; probably most effective of all was the contempt and jovial ferocity His insolence was the best cure for deference.’ (op.cit.a.14,15)) His intention was to destroy the unthinking deference upon which traditional sources of authority depended; his technique was to present the familiar in an unfamiliar fashion, to make men observe the old in an entirely novel manner. Burke provides a description of this process of demystification as acute as it is hostile:

All the pleasing illusions, which made power gentle, and obedience liberal…are to be dissolved by this new conquering empire of light and reason. All the decent drapery of life is to be rudely torn off. All the super-added ideas…are to be exploded as a ridiculous, absurd, and antiquated fashion.

On this scheme of things, a king is but a man; a queen is but a woman. (Burke. p.171. Of course he is not referring specifically to Paine.)

Paine himself offers what is by implication a valuable metaphor for this promise of shock demystification when, discussing that ‘silly contemptible thing’, monarchy, he writes:

I compare it to something kept behind a curtain, about which there is a great deal of bustle and fuss, and a wonderful air of seeming solemnity, but when, by an accident, the curtain happens to be open and the company sees what it is, they burst into laughter. (Rights of Man. p.155. The differing uses made of the metaphor of the theatre are illuminatingly discussed in Boulton, op. cit., p.143-5. See also Tolstoy’s description of the theatre as a source of corruption and mystification in War and Peace, Bk. VIII, Chap. IX, X.)

The principal target for this treatment in his political writings is monarchy, ‘the master-fraud, which shelters all others’. (Rights of Man. p.180.)

Demystification is as essential, if more difficult a task, in the realm of religion as of politics, the two congruent sources of the ignorance upon which tyranny was founded:

It has been the scheme of the Christian Church and all the other invented systems of religion to hold man in ignorance of his Creator, as it is of government to hold him in ignorance of his rights. The systems of the one are as false as those of the other, and are calculated for mutual support. (Age of Reason. p.116. Since examples of this literary technique can easily be located within any of Paine’s writings, it is unnecessary to burden the text with quotation. Here, for example, is his famous contemptuous dismissal of the claims to traditional authority of the English monarchy in Common Senses. A French bastard landing with an armed Banditti and establishing himself king of England against the consent of the natives is in plain terms a very paltry rascally original. The plain truth is, that the antiquity of the English monarchy will not bear looking into. (C.W., Ed.Conway. i.p.80-1) In Riots of Man (p.145-6). Kings succeed each other not as rationals, but as animals… It requires some talent to be a common mechanic; but to be a king requires only the animal figure of a man – a sort of breathing automaton.)

Precisely because he is encountering an area far more beshrouded in an unthinking superstitious reverence, this technique is most pronounced in The Age of Reason. It was in areas so heavily invested with a mysterious significance that it was necessary to ‘speak a language full and intelligible’, to ‘deal not in hints and intimations.’ (Age of Reason. p.222; cf. p.51.) His method is to present the Bible stories in the bald manner of everyday speech in order to demonstrate their patent absurdity when deprived of their traditional mode of presentation. Translated into such language; the narrative of the Fall and Atonement serves merely to ‘excite laughter or detestation by its profaneness’ and the Book of Genesis, once Moses’ claim to authorship is disposed of, becomes ‘an anonymous book of stories, fables and traditionary or invented absurdities, or downright lies. The story of Noah and his ark drops to a level with the Arabian Tales.’ (Ibid. p. 9,77. See also p. 86,90,106,109, etc.) After translating the narrative of Christ’s conception into ‘intelligible language’, he comments, ‘When told in this manner there is not a priest but must be ashamed to own it.’ (Ibid. p.128-9.) His later retelling of the conception narrative reinforces its absurdity by exiting incredulous laughter:

Were any girl that is now with child to say…that she was gotten with child by a ghost, and that an angel told her so ‘would she be believed? Certainly she would not. Why then are we told to believe the same thing of another whom we never saw, told by nobody knows whom, nor when nor where? Can any man of serious reflection hazard his future happiness upon the belief of a story naturally impossible, repugnant to every idea of decency, and related by persons already detected of falsehood?’ (Ibid. p.133,132.)

The vehement antagonism aroused by Such passages among his critics is perhaps an index of their effectiveness.’

It is common ground among students of Paine that his religious views were of long standing. (Clark. p.133-6. Conway, C.W. iv. p.4.) Conway’s apparently sound conclusion that the first part of The Age of Reason was written prior to Herschel’s discovery of Uranus in 1781 seems to have remained unchallenged. (Conway, ed.,00.iv.p.3-4. This argument is founded upon Paine’s references to only five planets, Saturn,Jupiter,Mars,Venus and Mercury, neglecting the recently discovered Uranus (Age of Reason, p.33). Conway argues that, considering his well-known and intense interest in astronomy, it is inconceivable that Paine would have remained ignorant of Herschel’s discovery for so long. Rather it would appear that Part I of The Age of Reason had remained in MSS for at least thirteen years before Paine, under threat of imminent execution, had it published without revision in France in 1793.) Thus before offering any consideration of the origins and pasture of Paine’s infidelity, it is necessary to provide some kind of solution to the apparently bibliographical problems: why did Paine delay the publication of The Age of Reason until 1793 and why was it published then? There seems little reason to question Conway’s view that the publication of at least Partl was the result of the threat of imminent execution, but this does not account for the continuing assault on Christianity which occupied the bulk of his remaining years. (C.W. iv. p.12.)

Paine’s fierce criticism of Christianity was to a considerable extent a reversal of earlier views. While he had always defended an unlimited liberty of conscience from a position essentially detached from formal Christianity, rather like Franklin or David Williams he had always defended religion. (71. ‘Common Sense’, C.W. (Weyde). Ii. p.162-3. Rights of Man, p.52. See chapter I, section III, on David Williams.) He avoided religious disputation, considering that ‘Every religion is good that teaches man to be good; and I know of none that instructs him to be bad.’ (Rights of Man. p.240; cf. p.251.) Nevertheless, with his Protestant background, he had always associated ‘spiritual freedom’ with ‘political liberty.’ (‘Thoughts on Defensive War’ (1775), C.W. (Weyde). Ii.p. 83) Monarchy he considered comparable to popery. (Rights of Man, p.158.) Before the 1790’s he did not see in religion a significant bar to political liberty. His observation in 1792 ‘that ‘religion is very improperly made a political machine’, while an intimation of a changing opinion, still did not lead him beyond the demand of liberty of conscience into an attack on Christianity itself. (Ibid. p.252.)

As regard the origin of The Age of Reason, as distinct from any earlier manuscript in Paine’s possession, Clark has argued that it was a growing recognition of the utilisation of religion for politically conservative purposes that was responsible for Paine’s increasingly emphatic opposition toward Christianity. (Clark. p.136.) Conway and Foner, following more directly Paine’s own explanation, have argued that it was events in France which stimulated his overt criticism of Christianity. (Conway, Life of Paine. Foner, Biographical Essay, C.W. of Paine, (19477375;5337:)) In his own later account of its origins Paine offers two main explanations:

In the first place, I saw my life in continual danger. In the second place, the people of France (sic) were running headlong into Atheism, and I had the work translated and published in their own language to stop them in that career (sic), and fix them to the first article… of every Man’s Creed who has any creed at all, I believe in God.’ (Paine. Letter to Sadams. 1802. C.W., iv. p.205. of Age of Reason. p.60.)

But Aldridge has offered the naively justifiable objection, that in a work intended to counteract atheism, the greater part consists of a criticism of Christianity. (A.O.Aldridge. Man of Reason. The Life of Thomas Paine., (Cresset Press, 1960). p.230.)) Such an objection is valid insofar as it draws attention to the connection discerned by Paine between such apparent extremes; ‘As to the Christian faith, it appears to me a species of. atheism; a sort of religious denial of God….(which) produces only atheists and fanatics.’ (The Age of Reason. p.28,165.)

Paine seems to have been anxious during the period of dechristianisation in France ‘lest in the general wreck of superstition…and false theology, we lose sight of morality, of humanity, and of the theology that is true. (Ibad., p.1.) He had clearly become steadily more pessimistic about the prospects of political action alone during the 1790’s, largely as a consequence of the unexpected strength of English reaction and the consuming ferocity of the French Revolution’s factional struggles, the source of major personal suffering on Paine’s part. Rights of Man contains numerous examples of Paine’s optimism concerning the prospects of a rapid and relatively peaceful revolutionising within the decade of the whole of Europe. (p.6; what we can foresee, all Europe may form but one great republic.’ (Rights of Man,p.185). For other examples of such optimism, see ibid. p.82,114,127,254.) Conceiving of an imminent revolution in England comparable to those in France and America, he writes ‘The present age will hereafter merit to be called the Age of Reason, and the progeny generation will appear to the future as the Adam of a new world. (Ibid.p.149.) Only a year later, writing to Jefferson in April, 1793, he observed that, as a result of what he considered the Jacobins’ immorality and imprudence in executing Louis XVI, these opportunities had vanished. (Paine. ‘Had this revolution been conducted consistently with its principles, there was once a good prospect of extending liberty through the greatest part of Europe; but now I relinquish that hope.’ In a letter to Denton dated 6. May, 1793, he wrote in a similar vein ‘I now despair of seeing the great object of European liberty accomplished, and my despair arises not from the combined foreign powers, not from the intrigues of aristocracy and priestcraft, but from the tumultuous misconduct with which affairs of the present revolution are conducted.’ (Cf. also ‘Forgetfulness’, (R.B.) ‘Ah, Francel thou hast ruined the character of a Revolution virtuously began and destroyed those who produced it.’ (Ibid., p.319).) Evidently Paine saw in the excesses of the French Revolution the legacy of the inhumanity fostered by Christianity. Describing the origins of The Age of Reason, he wrote in the Preface to Part ll:

The just and humane principles of the revolution…had been departed from. The idea…that priests could forgive sins had blunted the feelings of humanity, and callously prepared men for the commission of all manner of crimes. The intolerant spirit of Church persecutions had transfered itself into politics; the tribunals, styled Revolutionary, supplied the place of an Inquisition;, and the Guillotine of the State outdid the fire and faggot of the Church. (The Age of Reason. p.60.)

In 1797 he wrote:

When we reflect on the long and dense night in which France and all Europe have remained plunged by their governments and their priests, we must feel less surprise. than grief at the bewilderment guised by the first burst of light that dispels the darkness. (‘Agrarian Justice’.)

It was to help to destroy a religion whose consequence was a ‘practical atheism’ which had fatally marred the early achievements and anticipations of the Revolution that Paine wrote The Age of Reason.

His fundamental concern with the immorality fostered by Christianity is plainly evident throughout his theological writings.° (Cf. Conway. Life of Paine. Ii. p.198-9,202.) He argued that insistence upon exclusive divine revelations to particular individuals or groups had resulted in murderous intolerance between adherents of competing faiths and the neglect of.God’s universal revelation within the natural world and within the minds of men themselves. (The Age of Reason. p.160-1.) Far from improving human dispositions, ‘the obscene stories, the voluptuous debaucheries, the cruel and torturous executions, the unrelenting vindictiveness’ which form a considerable portion of the Old Testament are ‘a history of wickedness, that has served to compt and brutalise mankind.’ (Ibid.,p.13. The Age of Reason contains so many references to the immorality of the Bible, by which Paine means the Old Testament, that it would be superfluous to give examples. The following passage, from a letter dated May 12, 1797, summarises succinctly the grounds for his objection to the Bible: ‘It is from the Bible that man has learned cruelty, rapine, and murder; for the belief of a cruel God makes a cruel man.’ (C.W., iv. p.198). The complete letter is very important for an understanding of Paine’s theological views.) Paine’s central objections to Christianity from a relatively early age were primarily moral and religious. (For a famous autobiographical passage see The Age of Reason, p.41.) It was because of its inadequacy as a religion, because of its barbarous conception of a Deity and of the appropriate standards of human conduct that Paine regarded Christianity as inferior to Deism. (Ibid., 41-2.)

How inadequate any conception of Paine is which considers him as basically irreligious has, since first criticised by Conway, been repeatedly emphasised by his biographers. (Conway called The Age of Reason, ‘the work of an honest and devout mind’ (Life, ii. p.182). Weyde considered it ‘the work of a profoundly religious man’ and ‘essentially a religious work’ (Life of Paine, vol.1. of C.W., p.394,402). Aldridge writes ‘he at all times defended religious belief as socially beneficial and individually satisfying’ (Man of Reason, p.229). Leslie Stephen eventually modified his original opinion of Paine and wrote: ‘Paine’s appeal was not simply to

licentious hatred of religion, but to genuine moral instincts. His ‘blasphemy’ was not against the Supreme God, but against Jehovah’ History of British Thought in the Eighteenth Cent. (Harbinger,1962). i. p.392)) Paine’s fundamentally religious impulse permeates all of his writings on the subject. He indignantly rejected the appellation of infidel given to him by Erskine:

Mr. Erskine is very little acquainted with theological subjects, if he does not know there is such a thing as a sincere and religious belief that the Bible is not the word of God. This is my belief; It is not infidelity, as Mr. Erskine profanely and abusively calls it; it is the direct reverse of infidelity. It is a pure religious belief, founded on the idea of the perfection of the Creator. (Paine. ‘Letter to Erskine’, 1797. C.W., iv. p.230.)

In the same letter he wrote:

Morality and religion, which is the most solid support thereof, are necessary to the maintenance of society, as well as to the happiness of mankind. (Ibid. p.233.)

Paine always regarded Deism as a religious position and towards the close of his life considered himself, according to the signature appended to one of his letters to The Prospect, ‘A MEMBER OF THE DEISTICAL CHURCH’. (‘Prospect Papers”, 1804. C.W iv. p.334) Deism in its simplicity and genuine catholicity was the highest form of religion:

There is a happiness in Deism that is not to be found in any other system of religion. All other systems have something in them that either shock our reason., or are repugnant to it, and man, if he thinks at all, must stifle his reason in order to believe them. But in Deism our reason and our belief become happily united. (Ibid., p.316. For evidence that Paine’s religious impulse was not purely intellectual, see ibid., p.324-5 and The Age of Reason. p.42.)

A further demonstration of Paine’s religiosity can be found in his belief in personal immortality ridiculed as ‘superstitious’ by Carlile. (The Age of Reason. P.109,143,155,233-4. Carlile. The Republican, April 2, 1824, ix. P.437)

Although superficially paradoxical, it can be claimed that both his devastatingly effective critique of Christianity and the equally eloquent advocacy of natural religion originate in Paine’s fundamental interest in science: We have already observed a youthful interest in science which preceded any corresponding interest in politics. (See above.) As he observed, ‘The natural bent of my mind was to science.’ (Age of Reason. p.39.) It is interesting to observe that a developing acquaintance with natural philosophy, particularly astronomy, reinforcing the moral revulsion already in existence, proved the culminating agency in his rejection of Christianity:

After I had made myself master, of the use of the globes and of the orrery, and conceived an idea of the infinity of space and the eternal divisibility of matter, and obtained at least a general knowledge of what is called natural philosophy, I began to compare — or as I have said, to confront — the eternal evidence those things afford with the Christian system of faith. (Ibid., p.42.)

He proceeded to argue that an awareness of the plurality of worlds ‘renders the Christian system of faith at once little and ridiculous. (Ibid., p.43.) His conception of the mechanistic sublimity of the universe supplied the basis for the kind of ridicule of Christiality which caused either delight or apoplectic horror:

From whence then could arise the solitary and strange conceit that the Almighty, who had millions of worlds equally dependent on his protection, should quit the care of all the rest and come. to die in our world, because they say one man and one woman had eaten an apple? And, on the other hand, are we to suppose that every world in the boundless creation had an Eve„ an apple, a serpent, and a redeemer? In this case, the person who is irreverently called the Son of God, and sometimes God himself, would have nothing else to do than travel from world to world, in an endless succession of deaths, with scarcely a momentary interval of life. (Ibid., p.49.)

The introductory observation makes it clear that there is another aspect of Paine’s interest in science. For him natural philosophy leads on ineluctably to natural theology:

That which is called natural philosophy, embracing the whole circle of science, of which astronomy occupies the chief place, is the study of the works of God, and of the power and wisdom of God in his works, and is the true theology. (Ibid. p.28.)

Such an attitude to natural philosophy would vanquish both the fanaticism resulting from a search for God within any particular revelation and the atheism consequent upon the teaching, (of) natural philosophy as an accomplishment only instead of looking through the works of creation to the Creator himself. (‘The Existence of God’, 1797. C.W., iv. p.236 —40.)

Writing in 1804, he even uses that mainstay of natural theology, recently re-emphasised by Paley, the ‘watchmaker’ argument from design, to prove the existence of God.

The paradox of Paine’s attitude to science lies precisely in this combination of the platitudes of eighteenth-century natural theology and, considering the specific English context, the relatively novel critical use of science. The prominence in eighteenth century England of a natural theology based upon widespread popularisation of Newton is well known. (C.G. Gillispie. Genesis and Geology. (Harper Torchbooks, N.Y., 1959) chapter 1. P. Heimann. ‘Newtonian Natural Philosophy and the Scientific Revolution’. Hist. of Science, 1973.) A teleological conception of the universe was the common heritage of both rational Christian and freethinker. As Leaky observed in 1878’s, ‘One of the most remarkable differences between eighteenth-century Deism and modern freethinking is the almost complete absence in the former of arguments derived from the discoveries of science. (V.E.H. Lecky. A History of England in the Eighteenth Century. (Longman 477). iii. p.5-7.) Christianity customarily found itself under attack on the basis of its irrationality, immorality, and, increasingly, its inadequate historical veracity, rather than its incompatibility with the dominant Newtonian scientific world view.

How can the appearance in The Age of Reason of arguments derived from Newtonian natural philosophy alongside more traditional criticisms be accounted for? As a consequence of almost a century of itinerant scientific lecturing, Paine was able to assume the existence of a general scientific awareness among significant sections of his intended audience. (See chapter 1.) Paine’s natural theology consisted entirely of the popularised Newtonianism purveyed at these lectures. However, while these lectures were aimed, with ambiguous results, at reinforcing belief in God’s existence, they correspondingly proved dissolvent of the traditional conceptions of revelation and providence, of incarnation and resurrection, the theological and emotional foundations of Christianity. This perhaps may not have been significant during much of the eighteenth century when the debate on Christianity seemed confined to the respectable classes within a basically stable society and when even its principal defenders emphasised its rationality. But from the 1790’s onwards when, particularly as a consequence of the impact of Evangelicalism upon these classes, the most irrational components of Christianity, the emphasis on innate human depravity and the threat of hell, began to be utilised as ideological agencies of social control against an emerging popular radicalism, for the first time one encounters, in Paine’s Age of Reason, the use of scientific arguments against Christianity alongside the older ones mentioned above. It was at this moment that the radical implications of popular science first began to be evident, and it may be argued that Paley’s Natural Theology (1802) was as much a response to a fearfully anticipated spread of infidel doctrines as Watson’s Apology for the Bible (1796) or Wilberforce’s Practical View (1797).

But why should the advocacy of natural philosophy figure so prominently in The Age of Reason and Paine’s other theological writings? The importance of scientific instruction is clearly evident in Paine’s programme for his Theophilanthropic Church in Paris in 1797, which aimed to”combine theological knowledge with scientific’instruction’, principally for artisans. (Paine. C.W. ply. p.245.) There are, however, a considerable number of reasons why science should figure so prominently in the writings of Paine and later infidels. The appeal of science to Paine as a means of radically devaluing the learning and status of traditional intellectuals was absent among the earlier undemocratic opponents of Christianity. Science and traditional theology were the popular paradigms of useful and useless knowledge. Paine took the Baconian point of view that the progressive accumulation of the scientific knowledge resulting from the study of the works of ‘the great mechanic of the creation, the first philosopher and original teacher of all science’ was responsible for social progress.° (The Age of Reason. p.169.) Christianity, on the contrary, was responsible through its sustained persecution of science, for ignorance and stagnation.” (Ibid., p.36-7.) Paine asserted the value of scientific knowledge against the forms of the learning characteristic of traditional intellectuals, theology and the study of the classical, the ‘dead’ languages, distinguished equally by their practical inutility and their social exclusivity. (Ibid. 733-5.) The priests had substituted ‘the study of the dead languages instead of the sciences’ as a means of maintaining the ignorance upon which their authority was based. (Ibid. P.39.) This was because of the democratic principles inherent within scientific knowledge. (Ibid., p.35. The following quote should have appeared after the word ‘knowledge’ ‘the human mind has a natural disposition to scientific knowledge’ (Ibid.,p.150.)) Scientific knowledge was available and accessible to all literate and numerate individuals, offering a method of challenging and radically devaluing society’s traditional intellectuals and their ideology, for here in the person of Paine, was a self-taught artisan contemptuously vanquishing the clergy of England.

The sum total of a person’s learning, with very few exceptions, is a b, ab, and hic, haec, hoc; and their knowledge of science is three times one is three.

The culmination of this democratic attack on traditional intellectualism which aroused so much antagonism was his suggestion of replacing churches with lecture halls and the clergy with scientific lecturers, a position which was to remain fundamental to infidel theory and practice and whose implications have remained unappreciated and unexplored. (Ibid., p.169-70.)

It has been argued that the traditional conception of Paine as the individual solely responsible for extending infidelity to the masses, largely a consequence of the semi hysterical contemporary reaction to The Age of Reason, is to a considerable extent erroneous. That work’s novelty lay almost entirely in the context in which it was both written and received. This changed context, that of social revolution in France and crisis of authority in England, was responsible for The Age of Reason’s novelty and the reaction it elicited. This accounts for the firm association of congruent radical political and religious attitudes, on the part of both radical and conservative, absent in the previous controversies over religion which had taken place within a relatively stable society. Paine’s brusqueness of style, the source of much antagonism, was demonstrably an integral component of his total literary and ideological project. Similarly, the critical reliance upon an almost entirely internal textual analysis of the contradictions and absurdities of the Bible in addition to arguments derived from an elementary scientific knowledge simultaneously appealed to the self-taught audience at which Paine was aiming and gave them the means and confidence to challenge the traditional intellectual’s panoply of classical and historical learning so radically; devalued in his writings. What remains to be considered is the extent of the circulation and impact of The Age of Reason and other similar works in the 1790’s, insofar as this can be discovered.

Part 2: THE 1790’s: THE IMPACT OF INFIDELITY

By Michael J. Williams

IN A RECENT ARTICLE DEALING, principally with response of Christian apologists, Franklyn Prochaska has challenged what he considers to be a standard overestimation of the contemporary impact of Paine’s Age of Reason, by later authors. Of such writers, some of whom he briefly disbusses, he comments: ‘Judging Paine’s views clear-headed, they have supposed that they had extensive popularity.’ On the contrary, writes Prochaska, ‘It is doubtful whether Paine’s religious views ever gained such currency’ as has been claimed for them. (F.K. Prechaska. ‘Thome Paine’s The Age of Reason Revisited’. J1. Hist. Ideas. 1972. p.569.) As evidence for an assertion totally unencumbered by the kind of evidence any social historian would consider requisite, he observes that only one among over thirty pamphlets issued in reply defended Paine. (Ibid. pp.569-70.) Disregarding the fact that such a literary response is comparable quantitatively only to that elicited by Burke’s Reflections, which would apparently indicate some considerable impact, it completely, escapes Prochaska, operating within a purely intellectual history, that to have written and published such a defense would have been to court almost certain imprisonment.

Suoh blind misapprehension concerning the political context in which The Age of Reason appeared only serves to highlight the inadequacy of a purely internal intellectual history, which bases its estimation of a writer’s influence solely upon the study of a number of relatively easily accessible published texts commenting directly upon the particular work in question. This is especially so when one is considering the work of a writer aiming at reaching not the traditional intellectual strata whose literary output comprises the principal subject matter of the conventional intellectual historian; but that of such a writer as Paine whose avowed intent was to reach a popular audience. To assess the impact of any work which, like The Age of Reason falls into this latter category, a different kind of intellectual history is essential. Prochaska apparently realises the inadequacy of his own approach in his concluding observation that it would be rash to take its popularity (or unpopularity, MJW) for granted, particularly as our knowledge of radicalism and popular religion is so imprecise and the role of ideas so obscure”. (Ibid. p.576.) Such a qualification totally undermines his previous unsupported assertions concerning the popular impact of Paine’s work. Precisely because of the fragmented quality of predominantly literary sources, it is extremely difficult to assess the impact of ideas beneath those higher social strata – who have bequeathed the customary source material of the intellectual historian.

To discover the extent of the circulation and impact of The Age of Reason and other works of a similar character on, anatomical scale, would require immense labour and ingenuity for relatively limited and unsatisfactory results. So far as the circulation and impact of infidel writings in London during the 1790’s is concerned, we are fortunate in possessing two very detailed, reliable and accessible sources, W.H. Reid’s The Rise and Dissolution of the Infidel Societies of this Metropolis and Francis Place’s Autobiography, both of which have – recently become available in published form. (W.H. Peid. The Rise and Dissolution of the Infidel Societies of this Metropolis. (1800 Reprinted Cass 1972) Ed. M. Thale. The Autobiography of Frances Place (CUP., 1972)) Although Reid’s work has long been familiar to, and extensively utilised by historians of the period, there must necessarily have persisted some degree of skepticism about the reliability of such an avowedly polemical work. (See P.A. Brown. The Freneh Revolution in English History. 1918,. P.158. H. Collins, “The London Corresponding Society, in J. Saville, Democracy and the Labour Movement (Lawrence & Wishart, 1954) P.128-9; E.P. Thompson. The Making of the English Working Class. (Penguin, 1968). P.163,182. G.A. Williams, Artisans and Sans-Culottes C. (Arnold 1968). P.109-10. E. Royle. Radical Politics 1790-1900. Religion and Unbelief. (Longman,1971). p.22, 102.) Until the researches of the present author there was no means of verifying the author’s claim upon which the pamphlet’s aka source principally depends, to have ‘been involved in the dangerous delusion he now explodes,’ and an active infidel. (Reid. p.iii, iv) In his pamphlet he describes the London Magistrates’ suppression in 1798 of an infidel tavern debating society and the arrest of its members. (Ibid. p.13.) A brief account of this incident in the current Gentleman’s Magazine, mentions the presence among the arrested of W. Hamilton Reid, translator. (The Gentleman’s Magazine. LVIII (i). 1798. p.166.) Exact agreement between these narratives and the independent confirmation of Besides claims adds considerably to the value of his pamphlet as a source.

It is curious that in Reid’s pamPhlet.there is no reference to Place nor any confirmation of the latter’s account of his share in the publication of The Age of Reason. (Nor has it been possible to discover any reference to Reid’s pamphlet in the Place MSS, which is surprising considering the lengthy and precise account of Williams’ prosecution in the Autobiography. One can only assume that Place knew of neither Reid or his pamphlet.) There is neither any significant degree of overlap nor contradiction between the two works, which deal with differing and complementary aspects of the same phenomena: Of course, some doubt has been cast on the reliability of Place’s recollections of the Jacobins of his youth. As a consequence of his own later development, Place has been accused of overemphasising the sobriety and correspondingly underestimating the glamor and conviviality of as portrayed by contemporaries. (Thompson. pp.153,169-70.) This may be so far as Place’s political and social development is concerned, but as Thompson elsewhere observes, so far as free thought was concerned he lost his Jacobinism as he grew older and more superficially respectable. (Idib. p.846.) Should this be correct, as his steadfast support and consistent encouragement of Carlile during the 1820s indicates, then there is ‘reason to attach considerable reliability to recollections of his youthful atheism and co-partnership in the publication of an edition of The Age of Reason. Thus While our principal sources of information concerning London infidelity during the 1790s may be embarrassingly limited in number, their reliability and comprehensiveness provide ample compensation.

I.

Although published initially in France in 1793, Part I of Rights of Man first appeared in London early in 1794. (M.D. Conway. Ed. The Writings of Thomas Paine. R. Gimbel, “The First Appearance of Thomas Paine’s The Age of Reason”. Thomas Paine Society Bulletin. Jan. 1971, pp.5-6; Morning Chronicle, 6 February 1798, Place Collection, (B.M. Add. MSS.,38.i.f.251.)) No information available concerning numbers published but, according to the statement of Thomas Williams, confirmed by Lord Erskine, it was purchasable from ‘a great number of booksellers’ and had an extensive and free circulation initially. (Morning Chronicle, 6 Feb., 1798) It was in mid 1794 that Place read a copy of The Age of Reason borrowed from his landlord. (Place. Autobiography. p.126) Three further editions of Part I are catalogued in the British Museum as appearing in 1795 and Daniel Isaac Eaton published a cheap edition in 1796. After Part II was first published in London by H.D. Symonds at the relatively high price of 2/6 in October 1795. Paine wrote to Eaton asking him to publish a cheap edition, which appeared in January 1796. This edition was solely for 1/6 until its suppression at the time of Williams’ prosecution. (Conway. Ed. iv. PP. 13-14.)

The Age of Reason had presumably by this time aroused the considerable enthusiasm among large sections of the London Corresponding Society (L.C.S.) which was to lead to a plan in late 1796 to publish an even cheaper edition 461/- each which could be circulated among the Society’s expanding divisions. (Place. P159. Reid. P.54)

Thomas Williams, a bookbinder, in collaboration with Place; then a divisional delegate, proceeded to publish an edition of 2,000.of which all were sold. Only with his publication of a second edition of 7,000 independently of Place, which resulted in considerable sales, did The Age of Reason finally incur prosecution at the hands of the Proclamation Society. (Place. Pp.159-60.) ‘According to Paine, before his imprisonment Williams managed to sell at least 7,000 copies….’ The truth is thatTilliams never discontinued the sale of The Age.of Reason as long as a copy remained, but he ceased to sell them openly in the shop, and only supplied the trade or let persons whom he knew have them.’ As Erskine, hired by the Proclamation Society to prosecute Williams, commented:

That circulation was at first considerable, but became at last so extensive, and from the quarter whence it came, and the manner . in which it was propagated, became so dangerous to the public, that the prosecutors thought it a duty incumbent upon them to bring this prosecution. (Morning Chronicle 9 .6 Feb, 4 1798.)

Thus it was not so much the actual publication of Paine’s work, but its increasing circulation by Jacobins among the London poor, which inspired its ultimate prosecution. Williams eventually received what the judge considered a mild sentence: a year’s hard labour in Cold Bath Fields. Despite Williams’ imprisonment, The Age of Reason continued to circulate surreptitiously. As Place wrote at the time:

At the time as there had all along been there were many different editions of The Age of Reason on sale, as there was for a long time afterwards, until the demand declined, but the book has never been out of print, and never has there been a time when any difficulty to obtain copies existed. (Place. p.169)

Mayhew has a tale from ‘the early nineteenth century about the manner in which The Age of Reason was sold by an old London bookseller:

‘If anybody bought a book and would pay a good price for it, three times as much as it was marked, he’d give the Age of Reason…. The old fellow used to laugh and say his stall was quite a godly stall, and he wasn’t often without a copy or two of the Anti-Jacobin Review, which was all for Church and State and all that, though he had ‘Tom Paine’ in a drawer.’ (H. Mayhew. London Labour and the London Poor (1851))

Although it was the only one prosecuted, The Age of Reason was not the only infidel work in circulation during the 1790s. (Of. Thompson. p.107.) Principal among these others was Volney’ Ruins of Empires,” of which at least three editions were published in 1795-6. (B.M. Catalogue of Printed Books.) Unimpeded by prosecution, according to Carlile, writing in 1820, it found a great circulation in England, at least to the extent of 30,000 copies. (24. The Republican p18, Feb 4 1820. ii: P.148.) Among other works d’Hoibachl’s atheistic System of Nature, translated by a person confined in Negate as ‘a patriot,’ was published by the LOS in weekly numbers. Reid considered these two works, which’ were looked’ upon retrospectively by him as ”The Hervey of the Deists….and the Newton of the Atheists,’ to be no less influential than Paine’s more notorious work:

Nothing like a miraculous conversion of the London Corresponding Society is to be imputed to Mr. Paine’s Anti-theological Work. On the contrary, their minds were prepared for this more popular performance, by these more learned and elaborate productions. (Reid. p.6. It was probably this work, published in 6d. numbers by one Kearsley, which transformed the young William Hone into an atheist: ‘It caught my imagination and it brought upon me to believe in what its object was to prove, that in nature there was nothing but Nature (I forbear to mention the title): F.W. Hackwood. WilliamHone: His Life and Times. (T. Fisher Unwin, 1912). p54))

Until well beyond the close of the period under study these two works were to remain, with The Age of Reason, the most influential within infidel circles. Hence any any estimations of lower-class infidelity which is, like Prochaska’s, based purely upon the latter must inevitably remain inadequate. (Prochaska. pp.569-70.)

Other less influential works circulating among LCS members during the 1790s – included Northoote’s Life of David, in a small edition and the projected republication of Annet’s writings discontinued after three installments as a consequence of Williams’ prosecution. At the LCS club rooms the works of Voltaire and Godwin were available and the lectures delivered at the Temple of Reason in Whitecross Street in 1796 were based on those of David Williams. Other projected publications included The Beauties of Deism; A Moral Dictionary; Julian against Christianity and lastly, that Paragon of French Atheism, LE BON SENSE.” (Reid. p.6-8. Place. p.136.) Voltaire’s Philosophical Dictionary remained in circulation throughout this period, and Helvetius and Rousseau were available for those few, who like Place and other LCS veterans, could read French. (Reid. P.89, A.M.D. Hughes.The Nascent Mind of Shelley (OUP. 1947). P.83. A Pocket Edition of The Philosophical Dictionary was published in London in 1796 (B.M.Catalogue).)

Despite fairly reliable evidence for the circulation of The Age of Reason in Cork, alarmist reports that the miners of Cornwall and the colliers of Newcastle were selling their bibles.to purchase To Paine’s Age of Reason, and a contemptuous reference to the circulation of (Voltaire’s) worst works on dirty paper and in worn type by travelling auctioneers and at country fairs,’ there is little easily accessing information concerning the circulation of infidel works beyond the metropolis. (Nigel H. Sinnott. ‘Dr. Hincks and The Age of Reason in Cork.’ TPS Bulletin, Oct. 1971. R.A. Soloway. Prelates and People. (R.K.P. 1969.) p.39. R. Southey. Letters from England. (1807 Reprinted. Cresset Press. 1951),. P.400) Only an assiduous search beyond the opacity of any individual researcher among County records, local newspapers and magistrates’ reports, would yield even approximately adequate information. (See Williams, p.116.) On the basis of information referring only to London it is impossible to avoid the conclusion that infidelity had a considerable popular impact during the 1790s. It is likely that sales of The Age of Reason reached a figure of between ten and fifteen thousand, with a potential circulation many times this number.

So far our attention has been confined to questions relating to the publishing history and circulation figures of infidel works during this decade. The alarm felt about this phenomenon among ruling class circles has already been observed. But to what extent was the alarm concerning the popular dissemination of infidelity and the association between it and political radicalism justified? Was it unfounded hysteria or political manipulation of middle class responses as has been suggested, or was there some foundation to these claims, at least as far as London, the inevitable source for assertions concerning national phenomenon was concerned? (Cf. Southey’s comment quoted in Part 1. TPS Bulletin. No.2. Vol.5. 1965)

II.

There is reliable evidence of this association between infidelity and political radicalism within the LCS, not merely its final years of division and decay, but from its very inception and at the height of its development. It has been argued that during the eighteenth century the principal locus of popular freethought, normally in association with a putative or actual political radicalism, was the tavern debating society. Both Thelwell and Gale Jones, who was to remain a prominent London infidel for close on half a century, entered Jacobin politics from the world of the debating society. Brown noted the extent to which in the early 1790s Jacobinism was identified with debating clubs. Indeed, it could with justice be claimed that the debating society, far more than the Methodist class-meeting, provided a body made organisational model for the LCS. In April 1792 the old Coachmakers’ Hall Society for Free Discussion was ejected from its quarters and a similar society in Ipswich was dispersed by magistrates.’ (Brown. pp.59,83,85; Thompson. p.167 (The next reference should go before this)) Jephson argued that the Two Acts of 1795 were particularly directed against debating societies. (H. Jephson. The Platform: its rise and progress. (1892. Reprinted Cass, 1968). i. p.255.) In 1793, Eaton was prosecuted for publishing in his Politics for the People (the very title was a manifesto) a speech originally delivered by Thelwell at the Capel Court Debating Society emphasising the importance of ‘free discussion of political opinions, in public assemblies.’ (Politics for the People. VIII. Nov. 16, 1793. p.106.) Place’s well known description of the organisation of the LOS divisions gives similar emphasis to debate. (Place. p.131.) Apparently even after the formal suppression of the LCS in the late 1790s many activists returned, like Galleones, to the world of the debating society, then both ‘numerous and popular.’ (J. Britton. Autobiography. (1850). i. p.95. Brown. P.154) The ‘Spenson- ians’ met in this way in the early years of the next century and Gale Jones found himself propelled to the centre of the political arena as a consequence of a speech delivered at his British Forum in 1810. (B.M. Add MSS. 27.808 (3). p.201-2; T. Preston. Life and Opinions. (1817). Pp.20-1. Jephson. i. pp.336-8.) To a considerable extent the LCS emerged from a long tradition of free tavern debate which continued to flourish throughout the years of repression and quiescence. (Cf. T. Bewick. Memoir. (Bodley-Head, 1924). P.149; Thompson. pp.197-8.)

Such a connection in ethos between the LCS and earlier phenomenon makes the presence of infidels extremely likely, even before the growing impact of the circulation of infidel works in the mid-1790s. An atheist even before he joined the ICS., Place’s initial encounter with Jacobinism was via the freethinking landlord and LCS member from whom he borrowed Paine’s Age of Reason. (Place. p.126.) The LCS’s leading publisher, Baton, became an infidel while he was still a schoolboy. (State Trials. xxxi. p.938.) Judging from some later comments, Spence also was an infidel of sorts, or at least considerably opposed to traditional Christianity. (T. Spence. The Reign of Felicity. (1796). p.3.) In his account of a visit to Jacobins lower down the Thames Valley in 1796, Gale Jones wrote: ‘I do not profess to be a Christian.’ (J. Gale Jones. Sketch of a Political Tour Through Rochester, etc. (1796) .p.33.) On the other hand, of course, such prominent figures as Hardy and Bone were committed Christians. Nevertheless, Place was emphatic about the dominant attitude to religion prevailing within the LCS. ‘Nearly all the leading members were either Deists or Atheists – I was an atheist.’ ( B.M. Add. MSS. 27,608 (1). f. 115.) In his Autobiography, he expanded considerably on the subject of religious attitudes within the LCS.

If ever toleration, in its widest sense (sic), prevailed anywhere, it was in the London Corresponding Society. No man was questioned about his religious opinions, and men of many religions and of no religion were members of its divisions and of its Committees. Religious topics never were discussed, and scarcely ever mentioned. It was a standing rule in all the divisions and in committees, that no discussion or dispute on any subject connected with religion should be permitted and none were permitted. In private religion was a frequent topic of conversation. It was well-known that some of the leading members were Free Thinkers, yet no exception was ever made to any one of them on account of his speculative opinions, nor were ever brought into discussion. Thomas Hardy was a serious religious man, John Bone a good honest man, sometime assistant secretary, was a saint, and a busy man privately in his endeavours to make converts, many others were very religious men of various denominations.

Nonetheless, ‘The Society was stigmatized, as an association of Atheists and Deists whose object was to rout out all religion and all morals.’ (44. Place. p.197-8.)

This passage is sufficiently important to warrant lengthy. quotation. While remaining an admirable prescriptive statement of what Hobsbawm has characterised as the predominantly secular gone of the British labour and radical movement is as unreliable as the other descriptions of the LCS discussed by Thompson. Place was apparently also concerned with criticising the conservative propag- anda which which identified political radicalism with an intolerant atheism. Consequently, as on other occasions, he probably over-emphasises the rationality or the LOS members – so far as religion was concerned. Not only are such sweetly reasonable attitudes psychologically improbable within such a milieu, but on the basis of extensive research, admittedly principally in a slightly later period, it is impossible not to question its accuracy. Such reasonable and tolerant attitudes concerning emotionally and ideologically heavily-charged issues are unlikely.

Not only is Place’s account historically and psychologically inherently dubious, it is also contradicted by Reid’s portrait of the LCS, and also by a contemporary secret service report. James Powell, who had infiltrated the General Committee, reported that on 24 September 1795, “a letter was read from a numerous meeting of Methodists, belonging to the Society, requesting the expulsion of Atheists and Deists, from the Society.”‘ Powell considered that the rejection of the resolution would result in defections to be numbered in hundreds. This contemporary report contradicts Place’s description and confirms that of Reid, who ascribes the rapid predominance of infidelity within the Society to the appearance in 1795 of The Age of Reason. Such a predominance was not, however, gained, without considerable conflict, particularly in the General Committee, and a schism resulting in the formation of a new Civil and Religious Society, led by the booksellers Bone and Lee. Acknowledgement of ‘belief of the Holy Scripture, and that Christ is the Son of God became a necessary condition of membership. Apparently the refusal of Bone and Lee to sell The Age of Reason led to their prescription by the main body of the Society. (E.J. Hobsbawm. The Age of Revolution. (Mentor, N.Y., 1962). p.262; Thompson. pp.153,169-70.) On the basis of an apparently reasonably reliable account, Reid’s ascription of infidelity to the LCS in the post-1795 period seems justified, the origins of these developments in the appearance of Paine’s work provides sufficient evidence of its impact on the LOS, the predominant Jacobin organisation of the decade.

After the secession of the Christian minority in 1795 the Society became overtly infidel.

Impregnated with the principal objections of all the infidel writers, and big with the fancied importance of, being instrumental in a general reform, almost every division room could now boast its advocate for a new philosophy. In fact, such a torrent of abuse and declamation appeared to burst from all quarters at once, that as the idea of a Deist and a good Democrat seemed to have been universally compounded, very few had the courage to oppose the general current.

As a consequence divisional delegates began to be recommended for election as ‘A good Democrat and a Deist’, or more strongly, ‘That he is no Christian.’ (Ibid. pp.8-9. According to Thompson, Bone became LCS. Secretary in January, 1797. This could either have followed reconciliation with the LCS or have preceded the conflict described by Reid, whose chronology is unclear. (Thompson. p.182). Bone’s original secession does not seem to have been the result of conflict over religion. Hence some of these details in Reid’s pamphlet are rather unreliable.)

William Hone’s description of his youthful acquaintance with an infidel in 1795 provides us with a valuable illustration of the persuasive impact of infidel doctrines within the LOS at this time. Hone’s nineteen-year-old ex-school-fellow:

‘Calmly insinuated that I was in ‘leading strings,’ and should be good for nothing while I read silly authors, and took things on trust. I knew not what to answer, and in a few conversations I thought him unanswerable.’ He was my elder by three years, well educated and seducingly eloquent. He had settled to his own satisfaction that religion was a dream, from which those who dared to think for themselves would awake in astonishment at their delusion; that the human mind had been kept in darkness and men in slavery, but that the reign of Superstition was over… (etc.).’ (Hackwood. p.51.)

The flattering insinuations of the argument such as Hone has presented are so transparent as to require further comment.

Reid’s assertion that ‘from this period on, when leaders began to force their anti-religions opinions upon their co-officiates, it is undeniable that their intestine divisions hastened their dissolution more than any external obstacles’ undoubtedly requires some consideration. (Reid. p.9.) What relationship does the infidel attainment of hegemony within the LCS have with the Society’s decline in the late 1790’s. According to Thompson’s estimate, the adoption of The Age of Reason by the LCS and the consequent Christian secession Councils approximately, with its highest peak of membership, the last haIf of 1795. (Thompson. p.167. On the basis of a detailed consideration of the available evidence, Thompson estimates a membership of approximately 1,000 in late 1795 (pp.167-9). Cf. Williams. p.96.) Place’s gradual withdrawal from active participation in the Society’s affairs in 1796-7 was certainly unlikely to be an expression of dissatisfaction concerning its infidelity.” (Place. pp.151-4. Rather he resigned as it result of disagreement over tactical and organisational questions)) Thompson and Williams date the LCS collapse to around this period, ascribing it to government pressure and division among the leaders concerning the appropriate organisational structure and other questions of internal policy.’ (Thompson. pp.151,161-3.179,182; Williams. P.99-102.) There is little evidence that infidelity was the principal cause of the LCS’s decline; rather the evidence points to an open assertion of the infidel character of the organisation at the moment of its maximum political impact.