By James T. Boulton

Prose-especially political prose-written for a largely uneducated audience seems to present the literary critic with a difficult problem of evaluation. Writers-such as those examined by John Holloway in The Victorian Sage-who cater for an audience alert to subtleties of allusion, tone, rhythm, imagery and so forth, and who in consequence are able to manipulate a large range of literary techniques, confident of their readers’ response-such writers lend themselves readily to conventional literary analysis. But because our critical tools are not normally sharpened on his kind of writing an author like Thomas Paine tends to be ignored. He receives a nod from compilers of ‘social settings’ and ‘literary scenes’, as if what he had to say and the manner of saying it can safely be disregarded, but no serious critical attention.

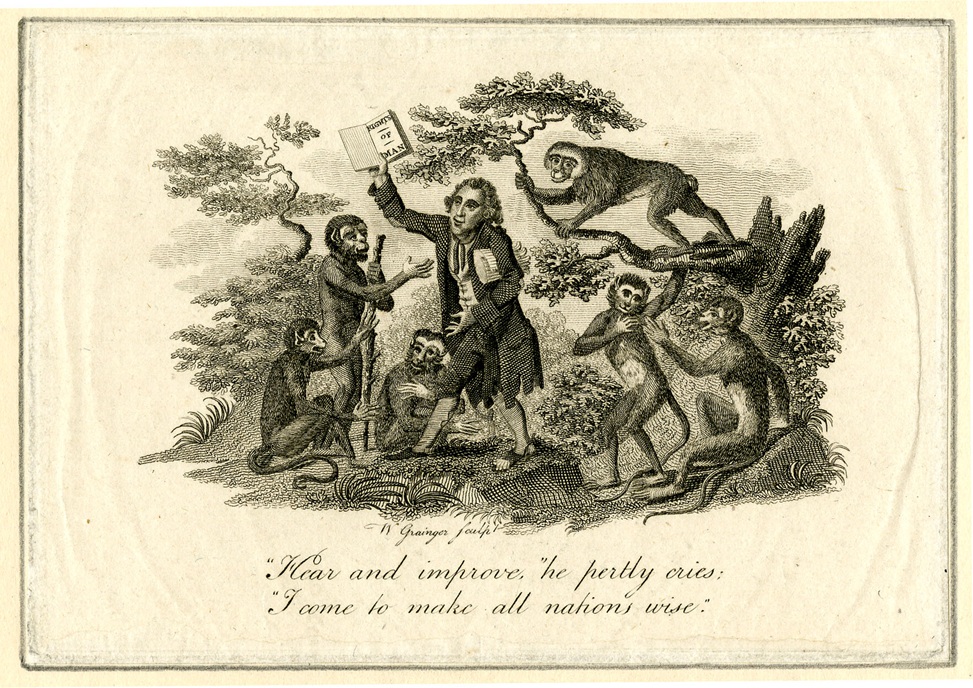

It is noticeable that no attempt has been made by literary critics to account for the remarkable impact of one of the best known political pamphlets, the first part of Paine’s Rights of Man (1791). There is no need to insist on the reality of Paine’s influence in his own day, it is too well known (though the reminder may be timely in view of the comp– lete absence of his name from the ‘Penguin Guide’ covering the Revolutionary period). And it is not adequate to leave it to the political historian to explain this influence, or merely to claim, with some eighteenth-century critics, that Paine’s was an appeal to the political have-nots against the ruling class. When it is remembered that upwards of fifty books and pamphlets were written in reply to Burke’s Reflections, many of them addressed to the same audience as Paine’s, this explanation obviously does not account for the distinctive success of the Rights of Man or for the sale (according to Paine) of ‘between four and five hundred thousand’ within ten years of publication.

One principal reason for Paine’s success was the apparent simplicity of his revolutionary doctrine and the lucid directness with which he expressed it. For example, he enters the great eighteenth-century debate on social contract; he rejects the notion that government is a compact between those who govern and those who are governed’ as ‘putting the effect before the cause’, and asserts initially the individuals themselves, each in his own personal and sovereign right, entered into a compact with each other to produce a Government: and this is the only mode in which Governments have a right to arise, and the only principle on which they have a right to exist. (Everyman’s edn.,p.47.)

Any government that, like the British, was the result of conquest and was founded on the power of a ruling caste and not on the free choice of the people, was ipso facto no true government. Paine will have no truck with Burkean arguments which start from the idea that man is the product of countless ages of human and political development; as in the quotation he insists on the beginning ab initio, ‘when man came from the hand of his Maker. What was he then? Man. Man was his high and only title, and a higher cannot be given him’ (p.41). The argument is naive but its persuasive force lies in its simplicity; only by its consequences does the reader recognise how deceptive and how rigorous is the apparent simplicity-man’s essential equality is established, privileges claimed as a result of so-called noble descent or hereditary succession, vanish, and it is an easy step to the assertion that sovereignty resides in the collective will of a nation (expressed by its freely elected representatives) and not in a single man who has come by chance to the position of king. From the same source springs the belief that ‘Man is not the enemy of Man but through the medium of a false system of Government’ (p.137), or, as he expresses it in Part 11 of the Rights of Man (published 1792), ‘man, were he not corrupted by Governments, is natur- ally the friend of man, and human nature is not of itself vicious’ (p.210). From this premise, expressed with such disarming directness, there follows a conclusion of vast importance for an age of dynastic conflicts: wars are the means by which non-representative governments maintain their power and wealth. (There is little wonder that Horace Walpole was perturbed when ‘vast numbers of Paine’s pamphlet were distributed both to regiments and shipped on the second anniversary of the fall of the Bastille.) (Letters, ed. Lewis, X1, 314)

Time and again Paine makes statements which appear commonplace in a context of political theory; they prove to be revolutionary in their implications.

The duty of man…is plain and simple, and consists but of two points. His duty to God, which every man must feel; and with respect to his neighbour, to do as he would be done by (p.44).

The assertion seems innocuous enough but, as in Swift’s writings, only when the reader has swallowed the bait does he realise how firmly he is hooked. The duty to one’s neighbour should be recognised by all men, by rulers as well as the ruled; Paine’s reader then discovers that the moral injunction has become a means by which rulers are to be assessed and that those who act well according to this principle will be respected, those who do not will be despised; and finally, the last jerk on the hook, ‘with regard to those to whom no power is delegated, but wh? assume it, the rational world can know nothing of them’. The logic by which this last position is reached is not unimpeachable but there is sufficient appearance of logic to obtain general acceptance of the conclusion from a quite impeccable premise.

There is no need to labour the point or to outline Paine’s political philosophy in full detail; based on the French ‘Declaration of the Rights of Man and of Citizens’ (which Paine includes in translation), his own doctrine has the same clarity that marks the deceptive simplicity of that document. Furthermore it is reinforced by Paine’s buoyant confidence: the ‘system of principles as universal as truth and the existence of man’ which had been operative in the revolutions of America and France would inevitably operate throughout Europe. It would, therefore, ‘be an act of wisdom to anticipate their approach, and produce Revolutions by reason and accommodation, rather than commit them to the issue of convulsions’ This conclusion to Part 1 is matched by the equally confident finish to Part 11 with its allegory of the budding of trees in February:

…though the vegetable sleep will continue longer on some trees and plants than on others, and though some of them may not blossom for two or three years, all will be in leaf in the summer, except those which are rotten. What pace the political summer may keep with the natural, no human foresight can determine. It is, however, not difficult to perceive that the spring is begun.

The allegory is as simple as a biblical parable, its message is clear and the experience it draws on is universal; moreover the writer has succeeded in detaching himself from his own powerful feelings and has embodied them in a vivid and concrete image which precisely conveys the desired sense of inevitability. Paine is indeed a conscious artist.

This conclusion so far lacks convincing evidence to support it but it is necessary to introduce it at an early stage. Paine was aware that he was – doing something new in the art of political pamphleteering; the first part of the Rights of Man was intended to test ‘the manner in which a work, written in a style of thinking and expression different to what had been customary in England, would be received’ (p.143). Immediate reactions to the literary quality of the pamphlet were, of course, coloured by political prejudice, but they remain important for our purpose. For Horace Walpole Paine’s style is so coarse, that you would think he meant to degrade the language as much as the government’ (Letters, X1, 239); the Whig pamphleteer, Sir Brooke Boothby, considered Paine had ‘the eloquence of a night-cellar’ and found his book ‘written in a kind of specious jargon, well enough calculated to impose upon the vulgar’ (Observations. Mr.Paine’s Rights of Man, 1792, pp.106n.,273-4); and The Monthly Review, to some extent sympathetic to Paine’s politics (it found his principles ‘just and right on the whole’), felt obliged to remark that his style is desultory, uncouth, and inelegant. His wit is coarse, and sometimes disgraced by wretched puns, and his language, though energetic, is awkward, ungrammatical, and often debased by vulgar phraseology. (May, 1791, p.81)

On the other hand, Fox is reported as saying of the Rights of Man that ‘it seems as clear and simple as the first rule in arithmetic’ (Atlantic Monthly (1859), 1V, 694).

Both extremes are to some extent right. The book is ‘clear’ but it is. also inelegant and occasionally ungrammatical; Paine can certainly be said to use ‘vulgar phraseology’. Yet it was an effective piece of pamphleteering, it ‘worked’: T.J.Mathias, writing in 1797, observed that ‘our peasantry now read the Rights of Man on mountains, and moors, and by the wayside’ (The Pursuits of Literature, 1V,ii); it handled serious and fundamental issues; and it provided a healthy counterblast to Burke. Moreover, it remains readable. The modern critic, then, finds himself in the position of having to accept that, given the urgency of the situation and the needs of the audience, Paine’s effectiveness depended in part at least on his ‘vulgarity’. Now ‘vulgarity’ in normal critical terminology is pejorative; it is the term used by a Boothby or an eighteenth century reviewer accustomed to aristocratic standards of accepted literary excellence; it is the term associated with the word ‘mob’ as Ian Watt has shown it to have been used in Augustan prose (Paper at the Third Clark Library Seminar, University of California,1956); and it is, of course, still current. But when the term is applied to Paine and his style the pejorative is completely out of place; ‘vulgar’ is necessary as a critical word but it should be descriptive, meaning, not boorish or debased, but plain, of the people, vulgus. Reluctance to accept this view leads to an unnecessarily restrictive limitation on the scope of literary criticism; criticism then is in danger of forgetting the principle of the suitability of means to ends and of becoming confined for its standards to those works only which are considered fit for aesthetic ‘contemplation’.

Admitting, therefore, that Paine’s achievement in the Rights of Man has little to offer to the ‘contemplative’, what can the critic say about the vulgar style? Take for example a passage ironically described by Walpole as one of Paine’s ‘delicate paragraphs’:

It is easy to conceive, that a band of interested men, such as placemen, pensioners, lords of the bed-chamber,lords of the kitchen, lords of the necessary-house, and the Lord knows what else besides, can find as many reasons for Monarchy as their salaries, paid at the expense of the country, amount to (p.113).

The humour is crude, decorum is absent, the alliteration is of the kind that occurs in agitated conversations, and the logic is questionable (for others besides sycophants can justify monarchy)-but what are the advantages of such a style? In the first place there is-here and throughout the book-a philosophical claim inherent in the language used: Paine is suggesting by his choice of idiom, tone, and rhythm, that the issues he is treating can and ought to be discussed in the language of common speech; that these issues have a direct bearing on man’s ordinary existence- monarchy involves the citizen in heavy taxation for its support; and that they ought not to be reserved (as Burke’s language implies they should) ,for language whose aura of biblical sanctity suggests that such issues are above the head of the common man. Paine’s language, his ‘vulgarity’, is indeed part of his critical method; to use a colloquial idiom about issues which Burke treats with great solemnity and linguistic complexity at once goes some way towards establishing the points just mentioned. Secondly, of course,Paine’s style gains in intelligibility and immediacy, and, as one result, his readers were provided with quotable phrases which would become part of their verbal armoury for use against the status quo. And, thirdly, there is a rombustious energy (such as Burke lacked) about this writing; it marks out the writer as a man of vigorous and healthy common sense. Paine, in fact, is creating an image of himself as one of the vulgar, using the language of the masses with just sufficient subtlety to induce their acceptance of his views. (His understanding of the importance of a persona is further illustrated and confirmed in the second part of the pamphlet where, for example, his sympathy with the economic circumstances of his poorer readers prompts him to remind them: ‘my parents were ‘not able to give me a shilling beyond what they gave me in education; and to do this they distressed themselves’ (p.234).) If one may accept Paine’s own phraseology as describing his intended audience-‘the farmer, the manu- facturer, the merchant, the tradesman, and down through all the occupations of life to the common labourer’ (p.113) – then his is the kind of idiom to make a direct impact.

It is, moreover, all of a piece with Paine’s criticism of Burke’s language More attention will be given to this matter later, but it might be observed here how frequently Paine selects a passage from the Reflections in order to point out the obscurity of Burke’s meaning.

As the wondering audience, whom Mr. Burke supposes himself talking to, may not understand all this learned jargon, I will undertake to be its interpreter (p.103).

Not only does this kind of remark cement the link between Paine and his unlearned reader, and give him an opportunity to score a witty point through the interpretation that follows, it also implies that the supporters of the status quo wrap up their sophistries in elevated obscurity. By translating Burke’s language into the idiom of everyday Paine diminishes his opponent’s stature and suggests that his seeming authority resides in the bombastic quality of his diction rather than in the validity of his argument. Paine, on the other hand, is seen to make his points in words that are readily understood; he does not have recourse (so he would have us believe) to any jargon, learned or unlearned, but uses vulgar speech, the language of common sense and common experience.

As his diction is of everyday, so Paine’s imagery and allusions are drawn from the common stock. He claims, for instance, that by requiring wisdom as an attribute of kingship Burke has, ‘to use a sailor’s phrase ….swabbed the deck’ (p.102); Court popularity, he says, a mushroom in a night’ (p.116); a State-Church is ‘a sort of mule-animal,

‘sprang up like capable only of destroying, and not of breeding up’ (p.67); or his famous comment that Burke ‘pities the plumage, but forgets the dying bird’ (p.24). Immediately intelligible as they are such phrases also suggest (as do similar ones in Bunyan) the writer’s nearness to and feeling for the life lived by his readers; he is using their phrases and thus implies his one- ness with their political position. He is, furthermore, adding to the stat- us of vulgar speech (as Wordsworth did in the first Lyrical Ballads) by showing its capacity for dealing with important issues at a fundamental level; Burke’s language, on the other hand, suggests that these issues are the exclusive concern of men using a refined and aristocratic medium.

Similar remarks are prompted by Paine’s limited use of literary allusion. Burke’s adulation of chivalry is ridiculed by a reference to Quixote and the windmills (p.22); the interrelation (for the French) between the fall of the Bastille and the fall of despotism is described as ‘a compounded image…as figuratively united as Bunyan’s Doubting Castle and Giant Despair’ (p.25); Burke’s researches into antiquity are not rigorously pursued, Paine asserts, in case ‘some robber or some Robin Hood should rise’ and claim to be the origin of monarchy (p.104); or again he enquires whether the ‘metaphor of the Crown operates ‘like Fortunatus’ wishing cap, or Harlequin’s wooden-sword’ (p.112). Where Paine refers beyond what might be called folk literature (and Don Quixote had assumed this character in England), he requires little in the way of literary training: a reference to the ‘Comedy of Errors’ for example, is valuable only for what is invoked by the title itself; it does not depend for its effectiveness, as do some of Burke’s Shakespearean allusions, on a knowledge of the play. The only literary knowledge on which Paine counts to any extent is a knowledge of the Bible and the Book of Common Prayer. He is confident that an allu- sion to the Israelites’ struggle for freedom, through the mention of ‘bond- men and bondwomen’ (p.72), will suggest an analogy with contemporary affairs; he clearly expects the language and rhythm of, ‘our inquiries find a resting place, and our reason finds a home’ (p.41), to be evocative, and the Litany to be recalled by, ‘From such principles, and such ignorance, Good Lord deliver the world’ (p.lll). It is noticeable, too, that the only occasion on which irony depends on a literary allusion, a biblical reference is used. Having asserted that a love of aristocratic titles is childish, Paine goes on: ‘A certain writer, of some antiquity, says: “When I was a child, I thought as a child….. (p.59). The irony is, of course, directed at Burke’s love of antiquity and precedents, but the interesting point is that Paine is attributing to the ordinary man the literary alertness to appreciate the irony. But, for the most part, Paine relies on the force of his facts and the arguments based on them, and thereafter only on his audience’s response to the metaphorical use of language which demanded a minimum of literary awareness. The metaphors involved in the description of the Bastille as ‘the high alter and castle of despotism’ (p.30) rely for their effect on political and religious prejudice; the claim that France had ‘outgrown the baby-cloaths of Count and Duke, and breached itself in manhood’ (p.59) requires none but normal experience to achieve its persuasive effect.

As in this last Paine frequently relies on metaphors which are rooted in popular experience. The experiments in aeronautics in the nine years preceding the publication of Rights of Man – culminating in the Channel flight of Blanchard and Jeffries in 1785-probably account for the charge that Burke has ‘mounted in the air like a balloon, to draw the eyes of the multitude from the ground they stand upon’ (p.53). This charge is reiterated elsewhere but here Paine gives it imaginative embodiment in a way that would have popular appeal. Again, Paine draws heavily on what Mr. Christopher Hill has called the ‘Norman Yoke’ tradition in English political literature, the theory that before 1066 the Anglo-Saxons were blessed with liberty and representative government, whereas the coming of the Normans meant the end of both and the establishment of oppressive monarchy and oligarchy.* The theory had been current since at least the sixteenth century, it gained new vitality in the writings of the Civil War period, it reappeared in Defoe and then,most vociferously, in Paine. When, therefore, Paine refers to the vassalage class of manners’ (p.72) that leads subjects to humble themselves in the presence of kings, or describes William the Conqueror as ‘the son of a prostitute and the plunderer of the English Nation’ (p.104), he is writing within a popular tradition which would excite even the most unsophisticated among his readers. Their tendency to look back to a golden age before the advent of tyrannic government would be powerfully stimulated by allusions to this unhistorical but very emotive and widely-held theory. But the kind of popular experience most often exploited by Paine is the dramatic and theatrical. The century abounded with farces, ballad-operas, ‘entertainments’, pantomime, and such-like theatrical performances; he clearly felt able to rely on experience of them. As Gay had satirised the Walpole ‘gang’ on the stage,so Paine uses stage-terms in his prose effectively to convey his contempt for the court and aristocracy. The unnatural degradation of the masses results, he says, in bringing forward ‘with greater glare, the puppet-show of State and Aristocracy’ (p33); courtiers may despise the monarchy but they are in the condition of men who get their living by a show, and to whom the folly of that show is so familiar that they ridicule it’ (p72); and the enigma of the identity of a monarch in ‘a mixed government’, when the king, cabinet, and dominant parliament- ary group are barely distinguishable,is described as ‘this pantomimical contrivance’ in which ‘the parts help each other out in matters which neither of them singly would assume to act’ (p.132). Furthermore, we hear of ‘the Pantomime of Hush’ of Fortunatus and Harlequin (favourite characters of pantomime), of the magic lanthorn, and so on. The achievement of this frame of reference is important. It obviously shows Paine drawing on experiences shared with his readers, and this is a significant factor in persuasion. It also allows him to ridicule the constitution Burke defends and generally identify it as a mode of comic entertainment (since Paine’s theatrical allusions are invariably used for the purpose of attack). Consequently the common reader is induced to regard the constitution in the same light and with the same insouciance as he viewed his dramatic entertainment. Some humorous as well as some serious purpose is involved. And it is noteworthy that while Burke himself frequently refers to the drama in the Reflections his is a different purpose: it is more obviously to arouse the emotional fervour normally associated with serious drama and to suggest that the proper state of mind for observers of the French Revolution is that appropriate to watching a tragedy.

To recognise that Paine also conducts a great deal of his literary criticism of the Reflections in terms of dramatic criticism is to see that the concept of drama is more than simply a persuasive technique: it embodies something central in Paine’s own thesis. In his ‘Conclusion’ he lays it down as an axiom that ‘Reason and Ignorance, the opposite of each other, influence the great bulk of mankind’ and that the government in any country is determined by whichever of these principles is dominant. Reason leads to government by election and representation, Ignorance to government by hereditary succession. Leaving aside the logic of this assertion it becomes plain that the axiom is organic with Paine’s choice of literary methods and the nature of his attack on Burke. It may have been no more fortuitous that what he felt to be a popular interest-theatrical entertainment provided him with a key metaphor to focus his analysis of Burke’s arguments and literary techniques; what is certain is that the essential business of drama-the imaginative interpretation of reality in terms of figures created to embody the dramatist’s attitudes and values- perfectly focuses Paine’s charges against Burke. (In this sense, for example, Burke ‘created’ the Marie Antoinette who appears in the Reflections; he did not present the woman from the world of fact) Used as a metaphor, the drama draws attention to the dichotomy between reason and ignorance, or reality and appearance, life and art, fact and fiction-between, indeed, the position claimed by Paine and the one he attributed to Burke. This is the conflict with which, in some shape or another, Paine constantly faces his readers; his choice of metaphor by which to conduct the argument suggests insight of no ordinary kind.

Once this is grasped, the references to drama fall into place. Burke, says Paine, is ‘not affected by the reality of distress touching his heart, but by the showy resemblance of it striking his imagination’; he ‘degenerates into a composition of art’; and he chooses to present a hero or a heroine, ‘a tragedy-victim expiring in show’, rather than the real prisoner of misery’ dying in jail (p.24). Again, Burke makes ‘a tragic scene’ out of the executions following the fall of the Bastille; unlike Paine he does not relate the factual circumstances which gave rise to the event.

As to the tragic paintings by which Mr. Burke has outraged his own imagination, and seeks to work upon that of his readers, they are very well calculated for theatrical representation, which facts are manuf- actured for the sake of show, and accommodated to produce, through the weakness of sympathy, a weeping effect. But Mr. Burke should recollect that he is writing History, and not plays, and that his readers will expect truth, and not the spouting rant of high-toned exclamation. (p.22)

I cannot consider Mr. Burke’s book in scarcely any other light than a dramatic performance; and he must, I think, have considered it in the same light himself, by the poetical liberties he has taken of omitting some facts, distorting others, and making the whole machinery bend to produce a stage effect. Of this kind is his account of the expedition to Versailles (p.34).

These are statements at length of Paine’s literary-political criticism of Burke; in them the clash between truth and fiction, reality and art, reason and imagination, concentrated by the metaphor of the drama, is evident enough. Proof of what is essentially the same approach occurs frequently elsewhere. Seen in this light Paine’s frequent use of factual information takes on an extra significance. He charges Burke with focusing attention solely on the deleterious effects of the Revolution and ignoring the facts which made it necessary and inevitable.

It suits his purpose to exhibit the consequences without their causes. It is one of the arts of the drama to do so. If the crimes of men were exhibited with their sufferings, stage effect would sometimes be lost, and the audience would be inclined to approve where it was intended they should commiserate (p.34).

Consequently when Paine provides factual details he is not only giving information to justify and propagate his own political attitudes; his intention is to confront ‘art’ with ‘life’ and to shatter what he cons- iders is an imaginative facade; he is also attempting to dispel the ig- norance which Burke fosters by his ‘dramatic method’ (as defined above) and which encourages the continued existence of despotic government. It is not necessary to labour any claim for Paine’s accuracy as literary critic although it seems to me that his line of approach is sound. Burke merits comparison with a dramatist; he concentrates attention on single human figures who embody attitudes and values he regards as important (or despicable); his narrative of events is essentially conducted by ‘scenes’; he stresses human actions to convey the character of a political movement; he does, in a sense, make a tragic heroine out of Marie Antoinette, and so forth. Paine, on his side, is justified in trying to break down the splendid, tragic isolation with which Burke invests the Queen; he is equally shrewd in trying to shift the emphasis that Burke places on Louis as the personal object of revolutionary assault, on to an issue of principle. There is, then, substance in Paine’s literary-critical approach; he shows perhaps more insight in this respect than many later critics of Burke; but what is chiefly important here is the way in which his literary criticism coheres with his larger political theory.

The corollary to his critical onslaught on Burke is that Paine should show himself guided by reason, that his style-by its simplicity and lucidity should mirror his emphasis on fact and common sense. He should, in other words, write the plain vulgar style in contrast to (what he would describe as) the refined and lofty obscurity of his opponent. If Burke ‘confounds everything’ (p.47) by failing to make distinctions and refusing to define his terms, Paine should work by definition and clarity; if Burke’s book is ‘a pathless wilderness of rhapsodies’ (p.40), then Paine’s should be well-ordered and comprehensible. If Faine’s writing is found to possess these desired characteristics one’s conclusion will not necessarily be that he is superior to Burke as a writer: one would conclude that his style and literary methods embody his political and moral values as effectively as Burke’s quite different style and methods are an embodiment of his.

In part the shape of the Rights of Man is dictated by Paine’s task: to refute the Reflections, He was compelled to take up separate claims advanced by his antagonist; where he felt it necessary he had to provide evidence omitted by Burke, as in his account of the Versailles incident or his review of the influences leading to the outbreak of the Revolution; and he had to argue his own political theory. The nature of his task led, then, to some disjointedness; he was determined to reason ‘from minutiae to magnitude’ (p.53). Again, the presence of a ‘Miscellaneous Chapter’ may be urged as proof of disorderliness. There is, in fact, some truth in The Monthly Review’s charge of desultoriness in presentation. Yet there is a sense in which this has to be. Some roughness of style, the absence of refinement and decorum, an energy that mirrored a scarcely controlled anger on behalf of the poor and unenfranchised-these things were signs of political good faith and honesty of purpose. From the nature of the theory argued in Paine’s book, he had to eschew the literary methods associated with an aristocratic culture linked, in its turn, with the politics of the establishment. There is, then, a significant truth in Sir Brooke Boothby’s sneering comment that Paine ‘writes in defiance of grammar, as if syntax were an aristocratical invention’ (Observations, p.106n.).

Whatever one’s final judgment on the mode of presentation, there is no doubt that Paine’s writing is simple and lucid.

There never did, there never will, and there never can exist a Barliam- ent, or any description of men, or any generation of men, in any country possessed of the right or the power of binding and controlling posterity to the ‘end of time’ (p.12).

When we survey the wretched condition of Man under the monarchical and hereditary systems of Government, dragged from his home by one power, or driven by another, and impoverished by taxes more than by enemies, it becomes evident that those systems are bad, and that a general Revolution in the principle and construction of Governments is necessary (p.134).

Writing such as this-and the examples are innumerable-has the merits of clarity, directness, energy, and the powerful conviction carried by the speaking voice. There is a balance about the phrasing which is not ‘literary’ but vulgar in the non-pejorative sense; it results from a determination to ensure the reader’s agreement by insistent affirmation, the accumulation of facts, and the colloquial phrasing of an accomplished on, popular orator. Where Paine attempts the kind of ‘literary’ style that is Burke’s province he fails utterly:

In the declaratory exordium which prefaces the Declaration of Rights, we see the solemn and majestic spectacle of a Nation opening its commission, under the auspices of its Creator, to establish a Government; a scene so new, and so transcendently unequalled by anything in the European world, that the name of a Revolution is diminutive of its character, and it rises into a REGENERATION OF MAN (p.99). This is rhetoric of the worst kind; it is vague and rhapsodic, pretent- ious and inflated-it is, indeed, guilty of the faults with which Paine charges Burke. But it is not normal: the two examples previously quoted are more representative of Paine’s general style. He is invariably concerned to place his views ‘in a clearer light’ (p.46); to enable us to possess ourselves of a clear idea of what Government is, or ought to be’ (p.47); and to avoid any word ‘which describes nothing’ and consequently ‘means nothing’ (p.60).

Paine obviously felt that an argument visibly divided into sections was necessary for his audience; his readers presumably required the kind of signposting denoted by phrases such as, ‘I will here case the compa- rison…..and conclude this part of the subject’, or, ‘it is time to proceed to a new subject’. Occasionally he contrives to turn what is avowedly a transition into an opening for humour:

Hitherto we have considered Aristocracy chiefly in one point of view. We have now to consider it in another. But whether we view it before or behind, or sideways, or any way else, domestically or publicly, it is still a monster (p.62).

The use of clearly-defined stages is a pointer to Paine’s understanding of the capacity of his readers. They required guidance and reassurance; they were not to lose themselves in ‘a pathless wilderness’. Nor could Paine count on a willingness in his audience to follow a lengthy discussion of abstract theory-hence his use of anecdote, of plain narrative carefully punctuated with information about the passing of time (‘He arrived at Versailles between ten and eleven at night’, ‘It was now ab- out one in the morning’, pp.37-8), of snatches of conversation with an ordinary soldier or a plain-speaking American, of humorous interjections, and the like. Paine was, indeed, well aware of the necessity ‘of relieving the fatigue of argument’ (p.57). And the constant use of facts, the frequent recourse to definitions, the impress of personal authority and experience (‘I wrote to (Burke) last winter from Paris, and gave him an account how prosperously matters were going on’, p.73), the enumeration of points established-in fact the general concreteness of reference recalling Defoe or the Swift of the Drapier’s Letters is based on a thorough understanding of the needs of his audience.

‘When men are sore with the sense of oppressions, and menaced with the prospect of new ones, is the calmness of philosophy, or the palsy of insensibility to be looked for?’ (p.31). Paine’s rhetorical question brings sharply into focus the difficulty posed by this kind of writing for the literary critic. By normal standards his writing must be rated low, and yet what has been said here should confirm his mastery of techniques appropriate to the occasion: if effective adaption of means to ends be a test of literary merit, the Rights of Man passes the test. The urgency of the times, the seriousness of the issues, and the needs both literary and political of his readers all underline the value of the vulgar style such as he provided.

University of Nottingham.

Reference

- See Christopher Hill, Puritanism and Revolution (1958), chapter 3, especially pp. 99-100.