By Robert W. Morrell

THE CONTENT MATTER of literature coming from the evangelical wing of the Christian Church is usually so silly as to deserve little serious consideration. From time to time you meet the odd item worthy of closer study, but such times are few and far between. A booklet I came across recently fits into the category of those unworthy of attention on all points but one, it is this one point that makes the booklet worthy of further consideration — but only in regard to this one issue. The booklet concerned is entitled The Impossibility of Agnosticism by the Reverend Leith Samuel (there is no indicatic,n in the booklet that the author is a professional religionist), an: is published by the Inter—Varsity Fellowship. The paint that arrested my attention was the claim made on pages nine and ten that Thomas Paine recanted of his deistical views.

Stories of Paine’s recantation or conversion were once the stock in trade of any self-respecting evangelical preacher or writer. In our more sophisticated age with its closer attention to detail, claims of such a specific nature have given way to those of a more general character, thus we hear little of the alleged conversions of Darwin or Bradlaugh, and more of the conversions of anonymous groups of men on rafts in the middle of the ocean after their ship had been sunk, through their prayers being answered, or so it is claimed. Mr.Samuel is, however, one of the old school, hence we get the story of Paine’s recantation, and, for good measure no doubt, that of Voltaire’s also.

Both Paine and Voltaire are, according to Mr. Samuel, en record as having, when faced with death, second thoughts. They were, our reverend cleric assures us, among “the most ardent (pursuers) of pleasure”, who, when approaching death, started to “sit up and think.” Now while being no expert on Voltaire I do know enough to reject Mr. Samuel’s claim in regard to the French philosopher; in Paine’s case, on the other hand, I have studied the matter in great depth and would retort to Mr. Samuel that he is talking just so much rubbish!

Mr. Samuel’s tale is taken from the memoirs of Stephen Grellet, an American religious fanatic of French extraction. He was told it by an employee, one Mary Roscoe. Another identical tale, unmentioned by Mr. Samuel, is derived from a Charles Collins, who was told it by one Mary Hinsdale. Both women are one, Hinsdale being the married name of Roscoe. Mary Roscoe was employed by a Quaker religious leader, Willett Hicks, a friend of Paine’s, during the time Paine was dying. She claims to have been sent to deliver an item to Paine and while there to have conversed. with him. Paine, she tells us, called out “with intense feeling”, “Lord Jesus have mercy upon me” and, “if ever the Devil has had any agency in any work he has had it in me writing that in (The Age of Reason) Paine is supposed to have asked Roscoe’s opinion of the book and later to have expressed a wish to like her, burned it. Having been but instructed. by Hicks to deliver something to Paine, the original claim, Roscoe developed it into one of “constant” attendance. Such is her tale as related by Grellel, and Collins, Needless to say there is not a scrap of evidence to corroborate it.

When the present writer challenged the truth of his claim that Paine had recanted, Mr. Samuel replied (letter of June, 29, 1967) that “The unimpeachable testimony of this gentleman (Grellet) seemed to outweigh anything found from contrary sources.” Unfortunately, as was later revealed, Mr. Samuel had not bothered to look up what the “contrary sources” had to say on the matter.

Roscoe’s tale was exposed as a lie by William Cobbett, who met and cross-examined both her and Collins. Mr. Samuel was quite stunned when this was brought to his attention, and makes (letter of July 7) the lame excuse that he was “unaware” of it – this after laying it down that Grellet’s testimony outweighed “anything” from “contrary sources”. It seems all too clear that Mr. Samuel just did not bother to do his homework, a fact which did not, however, prevent him from allowing no fewer than fourteen reprints of his booklet since it originally appeared in 1950!

William Cobbett while in New York in 1818 began to collect material for a life of Paine, in doing so he became acquainted with both Mary Hinsdale (Roscoe) and Charles Collins. Collins informed Cobbett that Paine had recanted. Cobbett requested evidence and Collins produced a paper containing a statement, so he maintained, made by Hinsdale. Armed with this document, Ccbbett called on Hinsdale-then living at 10, Anthony Street, New York, and showed it her, requesting its authentication, this Hinsdale refused to give, maintaining that she could give no information as to any of the document being true, she claimed never to have seen the paper before, nor to have given Collins any authorisation, to speak in her name. So the story should have faded into the mists of obscurity, like its alleged author. However, such is not to be the case for along comes Mr. Samuel to resurrect it. Roscoe, who, incidentally, took opium, also invented an•the/ recantation story, this time concerning a Quaker by name Mary Lockwood. Roscoe, meeting the brother of Lockwood (after the woman had died) told him his sister had recanted and wanted her (Roscoe) to say so at the funeral. This claim was fully and publicly demonstrated as pure fiction, or in other words, nothing but lies. Such, then, is the character of Roscoe; even Collins told another biographer of Paine, the American Gilbert Vale, that it was commonly held among her fellow religionists that no credit should be given to her statements. This, then, is the source of Mr. Samuel’s tale. Either Grellet was taken in by Roscoe – which is quite possible, or, and this is equally possible, he deliberately lIdd. So much for the “unimpeachable testimony” Mr.Samuel relies so uncritically on.

Willett Hicks, Roscoe’s employer at the time site was supposed t) be constantly attending Paine, pronounced her story as “pious fraud and fabrication”, he said that he had never sent her with anything to deliver to Paine, and that she had never spoken with him. He is also on record as telling of the many bribes he was offered to produce a statement from Paine recanting of his religious opinions.

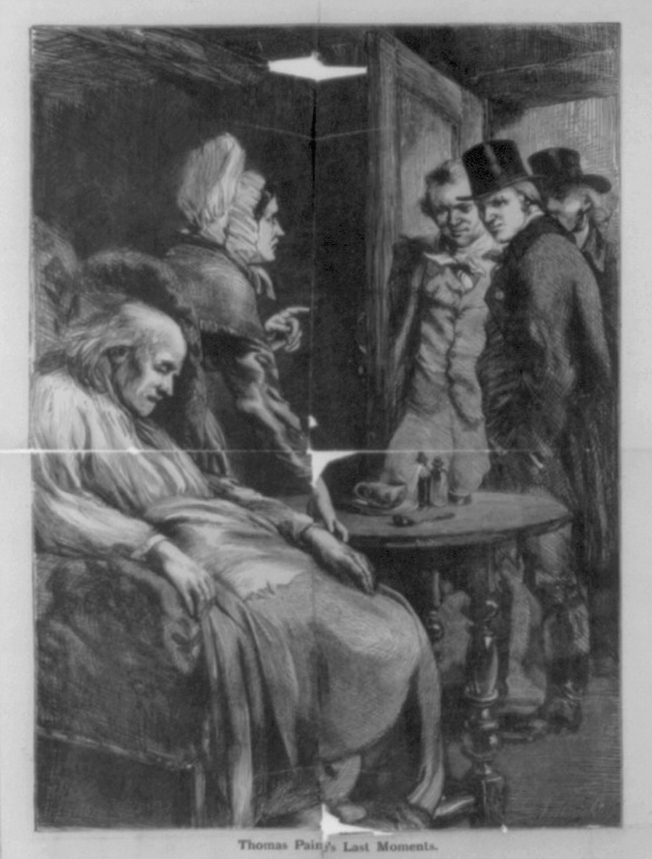

Against Grellet’s testimony must be set that of many others who confirm Paine retained his deistical views until the last. Wesley Jarvis tells us of Paine’s fear that stories such as Grellet relates would be invented after his death, thus he insisted on always having witnesses present when being interviewed. When Paine learned of the fatal nature of his illness he solemnly reaffirmed his opinions in the presence of a group of witnesses who included his physician, Dr. Romaine. Then there is the evidence of Dr. J.R. Manley – no friend of Paine – taken under oath. This gentleman testifies to the fact of there being no change in Paine’s religious outlook three days before his death, according to Dr.Manley, Paine flatly refused to accept Christ. Much more could be produced, but need we do so? The only unanswered question is why Mr. Samuel should have dragged up the tale once more, particularly as he admits to not having bothered to research it?

Mr. Samuel quite fails to grasp Paine’s intention in writing The Age of Reason, so much so that I suspect him as having never read it. Paine’s “unsparing temper”, to quote John M. Robertson, “was exactly that of the Christian Fathers against pagan beliefs and lore….it (is) essentially the tone of the religious man, offended by what he regarded as a superstition calculated to drive thinking men to atheism.” In seeking to promote his faith the Rev. Leith Samuel does himself and his religion little credit by bearing false witness, and I would remind him of the condemnation of this in Exodus 23;1., or the commandment against it, which is repeated in Rom. 13. Perhaps, then, he will do as Zacchaeus promised in Luke 19 and make amends. He is if nothing else under a moral obligation to do so as is his publisher. Future editions of The Impossibility of Agnosticism should have the tale expunged, as also that relating to Voltaire, and Mr. Samuel should display courage in apologising for smearing the memory of a man unable to make any reply. If he, and his publisher, fail to do this it will amount to a condemnation of everything he, and they, stand for.

“It is an affront to truth to treat falsehood with complaisance.” – Thomas Paine.