by R.G. Daniels

1981

Division of Vector-Borne Infectious Diseases

https://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvbid/yellowfever/index.htm

L-164, slide 24; 1312-81T

In 1805, Thomas Paine addressed a tract to the Board of Health of the United States entitled “Of the Cause of the Yellow Fever; And the Means of Preventing it” in places not yet effected with it. In 1807, Clio Rickman printed and published this tract in London, at Upper Mary-le-bone Street, with a foreword to the reader:

“I publish the following little tract of Thomas Paine’s in England, hoping that it may benefit society, by throwing some light on certain local diseases, even in countries, where it does not so particularly apply, as in America.

“I know also it will gratify many, to have anything from his pen; and to hear that the Author, though above Seventy, possesses health, fortune, and happiness; and that he is held in the highest estimation amongst the most exalted and best characters in America – That America, which is indebted for almost every blessing she knows to His labours and exertions.”

Present-day knowledge

AMARYL, or Yellow Fever, also called Yellow Jack because ships carrying crew or passengers with the disease flew a yellow flag, is a disease of Human Beings and some small animals, caused by a virus which is conveyed to man by the bite of a domestic mosquito, Aedes aegypti.

It was first identified in Barbados in 1647, and is thought to have been taken across the Atlantic in slave ships. It was first described in English by a physician, Hughes, in 1715. There were devastating epidemics in North America in the 18th. century, especially one in Philadelphia in 1793. There was even a small outbreak in the United Kingdom in 1865, in Swansea.

An attack of the disease, fatal in one in ten, confers. long-lasting immunity, and in areas where the disease is endemic the native population has considerable immunity.

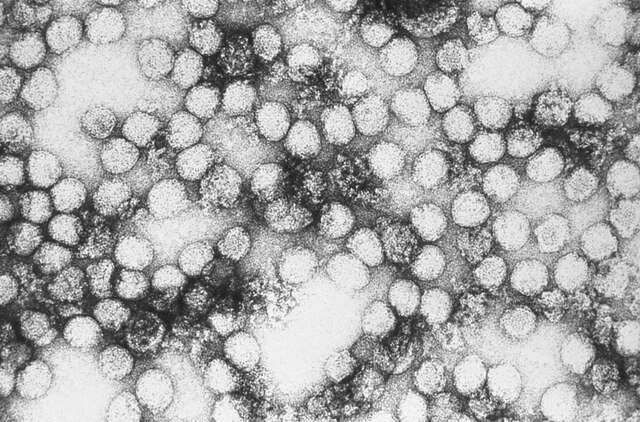

Viruses as a group of disease carrying agents were not discovered until 1887, and it was not until 1929 that the Yellow Fever virus was identified, although the mosquito Aedes aegypti had been inculpated in 1901.

Yellow Fever has killed more investigating scientists than any other disease. It is said that the stories of the Flying Dutchman and of the Ancient Mariner are based on a ghost ship abandoned as the crew succumbed to Yellow Fever.

The historical setting for Paine’s tract is interesting. Philadelphia, ‘as has already been mentioned, was the centre of a serious epedemic in 1793, just about the time that the negro slaves in Haiti began to revolt against their French owners. But it was not until 1801 that Toussaint L’Ouverture was finally victorious in gaining independence. By 1803 Napoleon Bonaparte had become jealous of this ‘Black Napoleon’ and formed a large armada in French, Spanish and Dutch ports under his brother-in-law, General Charles Leclerc, to sail to the West Indies and subdue the Haitians. However, the Haitians retreated to the mountains and the Yellow Fever destroyed two thirds of the French army, and although the French treacherously managed to abduct Toussaint to France, where he died the following year, Haiti kept its independence. Partly because of this bother, Napoleon sold Louisiana to America for fifteen million dollars in 1803.

Yellow Fever was to play its part in defeating other European projects in the New World. In 1882, Ferdinand de Lesseps, hoping to repeat his Suez triumph, expended large amounts of shareholders’ money in machinery, labour and bribes, in an attempt to link the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans at Panama. By 1889, however, the mosquito carrying Yellow Fever and Malaria had defeated him, and ruined his company.

It is apparent that Thomas Paine, who died in 1809, was not to know the scientific facts nor historical effects of Yellow Fever which are now commonly appreciated, and it is therefore interesting to read again his paper on its cause. It runs to more than 2,500 words, but about a quarter is taken up with an interesting discussion and description of experiments with marsh gas.

Marsh gas (“Fire-damp”) methane in its pure form, or, as we now know it, natural gas, and draw upon it from the North Sea, has been known for some centuries. Decomposition of organic matter at the bottom of rivers and ponds produces large amounts of impure and often highly inflammable air, and this can be set free by accident or by stirring the mud or exposing it to dry out.

Paine recounts an extraordinary episode in the autumn of 1783 when, Washington having withdrawn from New York and made his Headquarters at Mrs.Berrians, Rocky Hill, Jersey, it came to their knowledge that the creek under Rocky Hill had a fiery reputation it was said that it could be set alight. Washington knew of this and was interested enough to allow Paine to persuade him to try it. So, on the evening of November the fifth (a pleasant coincidence for the English fire-raiser), with General Lincoln, two aides- de-camp, some soldiers with poles, Washington at one end and Thomas Paine at the other, a scow sailed over the mill-pond on the creek, While the soldiers stirred the bottom of the pond, Washington and Paine held rolls of lighted cartridge paper over the surface of the water. Then, in a style that would please his amateur scientist friends, Priestley and Jefferson, Paine describes and proves that it was gas that was set alight by the illustrious and future President.

As regards Yellow Fever, Paine notes that it begins and continues in the lowest parts of populous marine towns near the water, especially around wharves. He makes the digression to discuss marsh gas, not because he feels that it is the cause of Yellow Fever, but he puts forward the idea that the gas is injurious to life, especially if it combines with a ‘miasm’ from the low ground newly produced when wharves are built, and that this pernicious vapour from submerged material is responsible for the disease..

Because he believes that it is wharf-making that contributes, if it does not actually cause, to fellow Fever, he ends the paper by suggesting new ways of making wharves lengthways along the river banks, and of iron rather than stone to make them cheaper, and that old wharves can be opened up so that the tide can wash in and around the banks of new earth disposing of any injurious vapours.

Finally: “In taking up and treating this subject, I have considered it as belonging to Natural Philosophy, rather than medicinal art; and therefore say nothing about treatment of the disease, after it takes place; I leave that part to those whose profession it is to study it.”

Although there is now a very reliable vaccine to prevent Yellow Fever, there is still no treatment except good general nursing.

The cause we know to be a virus carried in the saliva of a mosquito, and it is only by stringent international regulations that Yellow Fever is confined to a belt roughly 150 North and South of the Equator.

Thomas Paine’s comments about the disease occurring only where the banks are broken out and flattened to form wharves are entirely in keeping with the facts as we know them, for it is just in these areas that the mosquito finds the type of stagnant water it needs to breed. It is interesting that he uses much the same phrase in describing the site of the occurrence of Yellow Fever as does Sir Patrick Manson in his famous textbook on tropical diseases (6th. edition, 1919) – “The ideal haunt of Yellow Fever is the low-lying, hot, squalid, insanitary district in the neighbourhood of the wharves and docks of large sea-port towns…..a ‘place’ disease.”

Paine makes a point that the inhabitants of the West Indies and the Indians of America before the arrival of the white man, did not suffer from Yellow Fever, otherwise they would have forsaken the areas. This is quite true for the native population possessing ‘herd’ immunity, developed over the centuries.

In the Twentieth century, the disease would be prevented from arriving in the States by adequate vaccination and strict control of travellers. And the accumulation of pools of stagnant water close to dwellings and ships would likewise be prevented, or at least sprayed with mosquito killing chemicals.

The style in which this tract is written, Paine’s accumulation of facts, and his derivation from these of reasonable hypotheses, are entirely in the manner of the good natural scientist of his age.