By S.T. Miller

THE RAPIDLY GROWING importance of the town of Sunderland, by the end of the 18th century, is reflected above all in the coal export figures recorded in the Order Books of the River Wear Commission. The decade 1749- 1758 saw the export via the Wear of 1,5001000 chaldrons (Newcastle chaldrons), but by the decade 1789-1798 this total had risen to 2,900,000 chaldrons, i.e. doubling.

However the further development of the town was hampered by the absence of a bridge across the river at that point. Sunderland was, in fact,’ divided. into the “barbary coast” of Monkswearmouth on the northern side and Bishopwearmouth and Sunderland on the southern side. It was more usual in the late 18th century indeed to talk of “Sunderland and the Wearmouths”. The river could only be crossed by ferries (there were two ferries, the Panns Ferry and the very ancient Sunderland ferry which did not end until 1957, and whose establishment may have been coeval with that of the celebrated Monastery of Monkwearmouth. It may well be that the only serious mishap ever recorded as befalling the Sunderland ferry may have added impetus to the drive towards a bridge – for in the, late 18th century, on a Sunday evening, the ferry overturned in midstream and 22 people were drowned), fords higher up the river and the medieval Chester bridge. Nor was there a decent through road to Newcastle – Sunderland was unkindly regarded as being on “the road to no place”.

The problem was obvious enough as were the advantages to be gained by local business from a bridge. In 1790 a committee had been set up to look at the problem of the local ferry and arrived at the conclusion that a stone bridge should be set up. Yet this could be no solution since it would require supporting piers, and this would obstruct the considerable river traffic in coal which underpinned the prosperity of the town.

An answer to this was offered by Rowland Burdon. Born in 1756, he was the tenth in descent from Thomas Burdon of Stockton who had flourished in the reign of Edward IV. His father prospered as a member of the Company of Merchant Adventised of Newcastle and purchased the manor of Castle Eden. Rowland junior succeeded his father in 1786, and was also returned as member for the County in 1790 in an election fought against Sir John Eden and Ralph Milbanke (the father of Lady Byron). Indeed he represented the County as a moderate Tory in three successive Parliaments between 1790 and 1806 and only retired in the latter year owing to “circumstances over which he could exercise no control” which made him “the victim of misplaced confidence” (in fact all of his assets were lost in the crash of the bank – of Messrs Surtees and Co. which came in 1803). But Burdon was no “mere country gentleman”. As well as being an accomplished scholar and modern linguist he had also studied architecture under Sir John Some. He was also directly concerned in the problem of bridging the river because this would continue his Stockton-Sunderland Turnpike and an extension to Newcastle and South Shields would follow. In general there is every reason to believe that he was a leading figure in local commercial circles (“He did not out a shining figure as an orator, but as a practical man of business he stood second to none and as a commercial man he was known and respected by the wealthier merchants of Tyne, Wear and Tees…”).

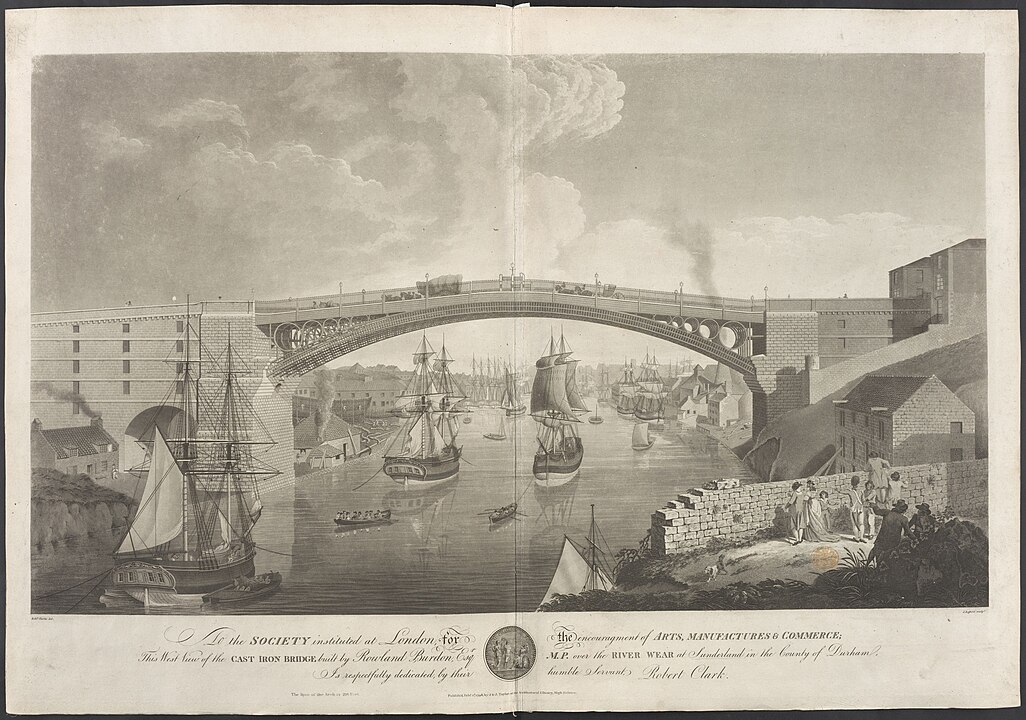

Burdon proposed that an iron bridge should be constructed in a single span, and his proposal was accepted. The Foundation stone was laid on the north side in September 24th,1793 (an inscription on the foundation stone begins “At the’time when the mad impetuosity of the French nation eager for what was wrong disturbed the nations of Europe with iron war, Rowland Burdon Esq., desirous of better things, determined to join together with an iron bridge the rocky and steep banks of the Wear….” The work was also decorated with the motto “Nil Desperandum Auspice Deo”, and it is recorded that many years after the completion of the bridge a non latinist clergyman was asked to explain it, and knowing the Paine claim to the design, confidently translated it as (“This desperate job was the work of a Deist”!) and Thomas Wilson (“an ingenious native”) was appointed to construct it. “It was opened for the accommodation of the public” on August 9th,1796 by Prince William of Gloucester escorted by a procession of local masons (as a precaution 1,000 locally stationed soldiers marched across it first) the “splendid show afforded the highest gratification to 50,000 persons”. “The ‘brass’ then retired to the Phoenix Lodge to regale themselves with an excellent cold collation” while “apposite toasts were drunk, several excellent songs were sung and the day was concluded with true hilarity and genuine mirth”.

The occasion was marked by the usual flurry of broadsheets and ballads, of which one may be singled out for its topicality if nothing else:

Ye sons of Sunderland with shouts

That. rival Oceans War,

Hail Burden in his Iron Boots

Who strides from shore to shore.

Oh may he firm support each leg

Oh much, oh much, we fear

Poor Rowland may outstretch himself

In striding across the Wear.

A Patent quickly issue ou

Lest some more bold than he

Should put on larger Iron Boots

And astride across the serf.

And let us pray for speedy peace

Lest Frenchmen should come over

And following Burden’s iron plan

From Calais strike to Dover.

The bridge consisted of six ribs of 5′ distance apart. There was a superstructure of planking to provide the base for a McAdam type road. The whole width was 32′ with a paved footway on each side, an iron palisadre and lamp posts at intervals. The bridge weighed 900 tons (the Iron Bridge weighed only 378 tons) of which 260 tons were iron (only 46 tons of which were wrought). The span was 236′ (an immense advance on the 100’ of the first Iron Bridge) and it was a segment of a circle about 440′ in diameter. The whole thing cost roughly £32,414 of which Burden subscribed £30,000 (the Iron Bridge cost a mere 16,000).

The expense of the bridge was broken down for 1792-1097 obtained in a parliamentary return obtained at the time by Mr. Warn, M.P.

The bridge was the subject of considerable praise at the time because of the novelty of its method and material of construction, its elegance and its scale (indeed it would seem that it was the biggest single arch bridge of its day). In 1818, Sir J. Brunel, in a report to the Bridge Commission, said ‘At the first sight of this extraordinary fabric I could not withhold the tribute of praise which the projectors and,promoters of the scheme are so justly entitled to, for the boldness of the designs, for the magnitude of the enterprise, considering the time it was suggested.’

Sir Robert Stephenson described it as ‘a noble and splendid structure which has no parallel in this or any other country.’

A complication must now be introduced to a hitherto straightforward story. In 1785, Thomas Paine had designed an iron bridge to span the Schwylkill river near Philadelphia without piers because “The vast quantities of Ice and melted snow at the breaking up of the frost in that part of America render it impractical to erect a Bridge on Piers.” He intended the bridge to be of 520 tons of iron ‘to be distributed into thirteen Ribs, in commemoration of the thirteen United States, each Rib to contain forty tons…’

In June 1786 he sent Benjamin Franklin to build a model bridge made of cast iron bars, and produced later an elaborate model that would bear the weight of three men. The State Authorities of Pennsylvania, however, were not interested — nor were the French forthcoming with any practical support although the French Academy of Science (to whom he submitted his scheme in 1787, sending at the same time a copy of the plan to Sir Joseph Banks to be shown at the Royal Society).

In 1788 Paine patented his design in London (Specification of Patents No.1667) and decided to go ahead with production himself. He had, in fact, to be satisfied with a sample rib of 88′ (moderating his ambition with ‘a little common sense’) by the brothers Walker of Rotherham (the very same firm which had manufactured Burdods bridge). He tested this section for both strain (it withstood a weight of 6 tons of pig iron — twice its own weight) and for the stresses of changes of temperature. In pieces it was as portable as bars of iron, and when it was dismantled was ‘stowed away in a corner of a workshop where it occupied so small a compass as to be hid away among the shavings.’

In June 1789 Paine prevailed on the Walkers to produce a bridge of 110′ span with five ribs to be erected across the Thames, then sold. By 1790 the parts were cast and shipped, however, Paine’s backer, the American Peter Whiteside went bankrupt and the bridge was constructed as an exhibition’ work on Leasing Green, Paddington, with a stilling per head charged to view it. Paine recorded in a letter to Sir George Stainton ‘that it is so much visited and exceedingly admired by the ladies, who, tho’ they may not be so much acquainted with mathematical principles, are certainly Judges of Taste’!

In Britain the reaction to his inflammatory rejoinders to Burke’s Reflections, and the attractions of France, led to Paine’s flight and the bridge was left in the hands of his creditors.

The two tales now become extricated. According to Michael M. Rix who follows the normal line of development, Rowland Burden knowing that they ‘were going begging. purchased the posts of Paine’s bridge and in 1793 set about adapting them to their new site’. The argument in favour of Paine is continued very recently by Mr. Tom Corte, the latest historian of Sunderland (‘…they made use of plans devised by the famous radical Thomas Paine…’), and the latest biographer of Paine (‘…the materials of Paine’s bridge and most of its principle were used to erect a bridge over the River Wear near Sunderland’.). No one has ever argued that Paine came to Sunderland and constructed a bridge, but it is usually claimed that he designed the bridge, or at least his design and the pieces of his bridge were pirated by Rowland Burden. These claims, however, were opposed, especially by Burden’s son. In the 19th century and to this day there is a strong tradition in Sunderland that Burden was the victim, that he designed and constructed the bridge and that the credit was stolen by Paine, or stolen for him.

‘It does not appear that the evidence for either of these claims has ever been seriously examined. This evidence can be usefully examined in three parts. There is largely hearsay evidence of observers, and there is the evidence of the initial specifications of patents.

Indeed there was considerable contemporary belief that Burden was the designer as well as the constructor. The Encyclopedia Britannica Supplement of 1803 concluded its entry under, ‘Arch’ by commenting on the Wearmouth Bridge, ‘The inventor and architect is Rowland Burden Esq., one of the representatives of that county in the present Parliament.” Mr.Thomas Bowdler, in a paper read before the Royal Society in 1797 remarked:

‘Iron bridges ah indeed been built in Coalbrookdale and in other places, but they were on the system of wooden arches rather than of stone. A plan for an iron bridge on a new principle was also invented by Mr. Thomas Paine, and exhibited some time ago near Paddington, but any person who examines that plan will perceive that it differs very essentially from the arch at Wearmouth…’

A Minute of the Proceedings of the Commissioners of the Bridge expressed thanks to Burden ‘…for his liberality to the public in constructing the bridge upon principles for which he, as inventor, has a patent, without accepting any pecuniary consideration for the patent right.’

‘The Gentleman’s Magazine in 1796 felt that it is proper that the public should be informed that R. Burdon Esq., is not only the inventor of the principle on which the bridge was erected, but the patron by whose munificence it has been chiefly carried into execution.’

Finally Surtees in his History of Durham says that ‘the use of iron had already been introduced in the construction of the arch at Coal brookdale, and in the bridges built by Paine, but the novelty and advantage of the plan adopted at Wearmouth on Mr. Burdon’s suggestion consisted in…’, etc.

Then gradually the name of Paine replaced that of Burden (although Aiss Williamson out that as early as 1812 Professor Charles. Hutton in his History of Iron Bridges praises Paine’s work). At first the claim is that the. materials used were those of Paine’s bridge, but by 1858 the Quarterly Review had dropped Burdon’s name out altogether (indeed the Review not only attributes the bridge to Paine, it also attributes it to him in terms of Burdon’s patent speaking of ‘framed iron panels radiating towards the centre in the form of voissoirs. Other commentators including Rix, not only give Paine the credit but also go on to describe the bridge using the detailed figures attached to Burden’s patent, thus implying either that Burden’s patent was ‘lifted’ from Paine’s, or, more likely, an ignorance of Burden’s patent. A small work published by the S.P.C.E. on bridges which had also given the credit to Paine was especially irritating to Burden’s son, ‘This I regard as the unkindest out of all. That my father who was an excellent Churchman, should be thus treated by that venerable society, while Paine the infidel, is promoted to the place of honour, is at any rate to the credit of their liberality, so often called in question, though it may be somewhat at the expense of their accuracy of statement…’.

This process was probably helped, as Burden’s son claimed, by the fact that after the loss of his fortune Burden ‘resigned himself thence forth quietly to that retirement which his straightened means had forced upon him. No wonder that the public heard little of him afterwards, and because he was a country gentleman ‘and that therefore there is great antecedent improbability that one of that class should have hit upon anything remarkable. To escape this difficulty the invention has been tried first on Wilson, then on Orimshaw„ the only other parties concerned in the building of the bridge, and these failing, it has finally been fitted upon Tom Paine. Wilson had been a school master, Paine a staymaker — my father, unfortunately, was a country gentleman’.

This sort of evidence cannot be conclusive because we have no way of knowing on what information these judgements are based.

Further’circumstantial evidence that has been adduced against Paine is that he was not the sort of man who would quietly have submitted to the stealing and exploitation of his own design. Miss Williamson does point out, reasonably, that during the building of the bridge Paine was in the Luxembourg Prison and in no position to be acquainted with events in Sunderland. On the other hand Sir Robert Smyth, a banker living in France and Paine’s friend, did challenge, at the time, the right of Paine to claim compensation, but although Paine returned to America in 1802 he never pressed his claim.

It could also be argued, circumstantially, that the Patents Office, even in the eighteenth century, was unlikely to allow patents for two bridge designs which were substantially the same.

Both Paine and Burden took out patents, the former in 1788 (No.1667), the latter in 1795 (No.2066). Obviously the problem should in theory be resolved on examination of the specifications, and, indeed, despite the availability of a number of ‘red herrings’ and problems of interpretation, this is decisive.

Burden’s specifications are very precise. The title itself is a good indication of the method, Application of Metal Blocks to the Construction of Arches. He describes the method of construction clearly:

‘…my invention consists in applying iron or other metallic compositions to the purpose of constructing arches, upon the same principle as stone is now employed, by a subdivision into blocks easily portable answering to the keystones of a common arch, which being brought to bear on each other, gives all the firmness of the solid stone arch, whilst by the great varieties in the blocks and their respective distances in their lateral position, the aid becomes infinitely lighter than that of stone, and, by the tenacity of the metal, the parts are so intimately connected that the accurate calculation of the extrados and intrados, so necessary in stone circles of magnitude is rendered of much loss consequence’.

The cast iron blocks (known in engineering terminology as ‘voussoirs’) were to be of 5′ depth, 4″ thickness, with a middle arm of 2′ length, and the top and bottom arms in such proportion as to make each block a segment of a circle. These blocks would then be fixed by means of malleable iron tie rods to form ribs (in the Sunderland bridge each rib included 105 blocks). The ribs would be joined and supported laterally by hollow tubes six feet in length and four inches in diameter.

Paine’s specification for Constructing Arches, Vaulted Roofs and Ceilings are, on the other hand, confused to some extent by the analogies he uses. ‘The idea and construction of this arch is taken from the figure of a spider’s circular web of which it resembles in section and from a conviction that when nature empowered this insect to make a web she also instructed her in the strongest mechanical method of constructing it. Another idea, taken from nature in the construction of this arch, is that of increasing the strength of matter by dividing and constructing it and thereby causing it to act over a larger space than it would occupy in a solid state, as seen in the quills of birds, bones of animals, reeds, cones.’

Burden’s son comments wryly that this language could embrace not only Burden’s bridge but also the catenary of the suspension bridge (spiders web) and tubular bridges (quills of birds,etc.), ‘Yet we presume Mr.Stephenson will not feel much uneasiness lest in succeeding generations the bridge over the Menai or Staawrence be attributed to the genius of Tom Paine, whilst his own name is struck out of the roll of inventors and consigned to oblivion’ (Robert Stephenson did, according to Burden’s son, write a letter to Burden’s brother stating that the two patents were clearly different).

However, it is clear from further reading that Paine’s concept was different, since he goes on to say:

‘The curved bars of the arch are composed of pieces of any length joined together to the whole extent of the arch and take curvature by bending. Those curves, to any number, height or thickness as the extent of the arch may require, are raised concentrically one above another, and separated, when the extent of the arch required it, by the imposition of blocks, tubes and pins, and the whole bottled close and fast together (the direction of the radius is the best) through the whole thickness of the arch, the bolts being made fast by a head pin or screw at each end of them. This connection forms one arched rib, and the number of ribs to be used .is in proportion to the breadth and extent of the arch and those separate ribs are also combined and braced together by bars passing across all the ribs and made fast thereto above and below, and as often and wherever the arch, from its extent, depth and breadth, requires’.

Further information as to the design is given by Paine in a letter to Sir George Stainton:

‘We soon run up a Centre to turn the arch upon, and begin our erection. The raising of an arch of this construction is different to the method of raising a stone arch. In a stone arch they begin at the bottom and work upwards meeting at the crown. In this we begin at the crown by a line perpendicular thereto and worked downward each way. It differs likewise in another aspect. A stone arch is raised by sections of the Curve, each stone being so, and this by concentric curves’.

In fact, Paine’s project was more appreciative of the potentialities of iron than either the Coaibrookdale Iron Bridge, based as it was on principles of wood construction, or Burden’s bridge, which, it was agreed by all observers, was based on the principles of stone construction.

It should be obvious from the above that what Paine was projecting was a modern girder type bridge, based on Bailey bridge or ‘meccano’ lines (otherwise it is difficult to see how it was so portable). So modern that Charles Schneider said, in his 1905 Presidential Address to the American Society of Civil Engineers, that Paine’s experimental bridge became the prototype of the modern steel bridge’.

It may be of course that Burdon did make use of the materials from Paine’s bridge. There is no evidence for this but it was not at all unusual that Burdon should go to the Walkers since he could easily have been aware of their experience, and it is equally possible that Paine’s materials should be worked upon with others. However, there the connection would end — the concepts were different, the spans different, and Paine’s design would require malleable iron rather than cast iron.

The obvious conclusion is, then, that Paine did not design the bridge at Sunderland, that Burdon did not use Paine’s design, and that not even did Paine and Burdon work on the same design at once. Any connection between Paine’s experiments with Burdon’s feat of engineering was purely coincidental.

The failure to recognise the contribution of Burdon to the development of Sunderland and the North East and the expansion of the application of iron, apart from the production of a beautiful bridge, is made worse in a way by: the fact that Burdon’s sole excursions from his enforced retirement after 1803 were directed towards the freeing of the bridge from tolls which were maintained by those who had acquired his interest in a lottery held in October 1816 in order to reimburse themselves. On 27th December, 1836 he wrote to the Sunderland Heralds ‘The object yet remains to be obtained of seeing Monkwearmouth Bridge toll free if ‘ the Commissioners will be pleased to look steadily at the object and by raising money at a lower rate of interest or such other means as may occur to them would endeavour to discharge the claims of those who have by lottery obtained an infamous power over the tolls, it would give me more substantial satisfaction than my memorial that could be raised by means which the public would have the right to consider a misapplication of their funds’.

He died in 1838 aged 82. Not until 1846 was the toll on foot passengers discontinued and other tolls reduced by 50%* It was announced that a profit of £79,666 had been obtained from the bridge since its opening in 1796, although Burdon’s original concern was not, apparently, with profit. Not until 1885 was the bridge freed from toll completely by then it had been remodelled by Sir Robert Stephenson (although he used the same ribs) in 1859. In 1929 this structure was replaced by the modern ‘near perfect replica of Newcastle bridge and Sunderland lost one of its unique features forever.

Dept. of Education,

Sunderland Polytechnic,

Chester Road,

Sunderland,

Co.Darham,

SR1 38D.