By R.G. Daniels

IN PART 1 OF THE AGE OF REASON, written during the French Revolution and completed we are told only a matter of hours before his arrest, Paine devotes some pages to a general account of astronomy as an introduction on Christian theology. It is worth looking at this accountto in the light of knowledge as it was then and as it is now, and also to consider sources of Paine’s information.

He begins with a comment on the ‘plurality of worlds’, an idea from the ancient philosophers gaining acceptance in scientific circles in the eighteenth century largely by virtue of the work of Halley and Herschell, indicating the vastness of space and the lack of uniqueness in the existence of the Earth.

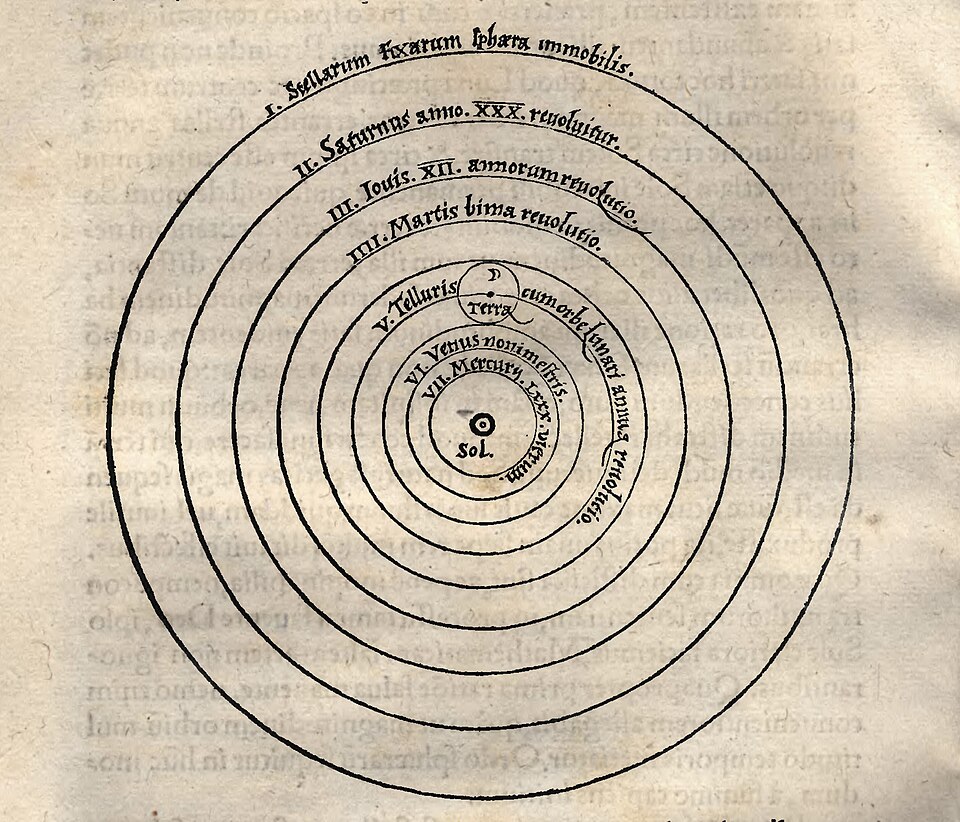

He then describes the Solar system — the sun and its six satellites or worlds, all in annual motion around the sun, some satellites having their own satellites or moons in attendance, each world keeping its own track (the ecliptic) around the sun. Each world spins around itself (rotates on its own axis) and this causes day and night. Most worlds, in their self-rotation, are tilted against their line of movement around the Sun (the obliquity of the ecliptic) and Paine quotes the correct figure for Earth of 212 degrees. It is this tilt that is responsible for the changing seasons and for the variation in the length of day and night—time over the world and throughout the seasons. Earth makes 365 rotations in one year’s orbit of the Sun.

The six planets are then described with their distances from the Sun. These figures are incorrect now, but the figure he gives for Earth’s distance, 88 million miles, agrees with the eighteenth century figure derived from Kepler’s Laws of about 1620. In 1772, Bode formulated his empirical law of planetary distances giving the measurements more accurately than hitherto, but this information would not have permeated the circles in which Paine moved after his departure for America.

As proof that it is possible for man to know these distances he cites the fact that for centuries the precise date and time of eclipses and also the passage of a planet like Venus across the face of the Sun (a transit) have been calculated and forecast.

Beyond the Solar system, ‘far beyond all power of calculation’ (until Besse’ calculated the distance of 61 Cygni in 1838) are the “fixed” stars, and these fixed stars ‘continue always at the same distance from each other, and always in the same place, as does the Sun in the centre Of the system’. William Herschell communicated to the Royal Society in 1783 that this was not in fact so, and that all stars were moving but at rates indiscernible as yet to man. Paine repeats a current idea that these ‘fixed’ stars or suns probably all have their own planets in attendance upon them. Thus the immensity of space.

‘All our knowledge of science is derived from the revolutions those several planets or worlds of which our system is composed to make in their circuit round the Sun’. He regards this multiplicity as a benefit bestowed by the Creator — otherwise, all that matter in one globe with no revolutionary motion (there are echoes of Newton here) would have deprived our senses and our scientific knowledge, — ‘it is from the sciences that all the mechanical arts that contribute so much to our earthly felicity and comfort are derived’. He even suggests that the devotional gratitude of man is due to the Creator for this plurality.

The same opportunities of knowledge are available to the inhabitants of neighbouring planets and to the inhabitants of planets of other suns in the universe. The idea of a society of worlds Paine finds cheerful – a happy contrivance of the almighty for the instruction of mankind. What then of the Christian faith and the ‘solitary and strange conceit that the Almighty, with millions of worlds equally dependent on his protection, should devote all his care to this world and come to die in it’? ‘Has every world an Eve, an apple, a serpent and a redeemer?’ And so to the rest of The Age of Reason.

Where did Paine obtain his astronomical information and instruction? It is unlikely he had any books with him, he certainly did not have a bible. Paris, seething with the Revolution, had Astronomer Bailly as mayor until his execution in 1793. Condorcet (author of Progress of the Human Spirit) and Lavoisier (the’father of modern chemistri9 were deeply involved and died in the Revolution. Laplace (‘the French Newton’) and astronomer Lalande were also in and around Paris at this time. But all these scientists, like Paine, would have been too busy to teach or discuss astronomy. So Paine would have had to recall the lectures and practical demonstrations he attended in London before he went to America. They were given by Benjamin Martin, James Ferguson, and Dr. John Bevis. It is worthwhile looking at the careers of these three men, mentioned only by surname early in The Age of Reason, because the facts, derived from the Dictionary of National Biography, afford some light on Paine’s life in London.

Benjamin MARTIN (1704-1782) – A ploughboy to begin with, he began to teach the ‘three Rs’ at Guildford while studying to become a mathematician, instrument maker, and general compiler of information. He read Newton’s Opticks (1705) and became an ardent follower of his ideas. He used a £500 legacy to buy instruments and books in order to become an itinerant lecturer. He had over 30 major publications to his name as well as a number of inventions. He perfected the Orrery (not named after its inventor, as Paine states, but after the patron of the copier of the invention), and used his own version in his lectures. He lived in London, at Hadley’s Quadrant in Fleet Street, from 1740 onwards. He died following attempted suicide in 1782.

James FERGUSON (1710-1776) – A shepherd-boy in Banffshire at the age of ten. He took up medicine at Edinburgh but gave up to sketch embroidery patterns and then to paint portraits and continue his interest in astronomy. He used the income from his painting to enable him to begin as a teacher and lecturer in London in 1748, where he had arrived five years before. His book, Astronomy explained on Sir Isaac Newton’s Principles (1756), went to at least thirteen editions and was used by William Herschell for his own study of astronomy. George III called on Ferguson for tuition in mechanics, and he was made a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1763. He became a busy lecturer in and around London in the middle of the eighteenth-century, sometimes also travelling to Newcastle, Derby, Bath and Bristol for speaking engagements. He occasionally had public disagreements with his wife – even in the middle of lectures!

Dr. John BEVIS (1693-1771) – He studied medicine at Oxford and travelled widely in France and Italy before settling in London prior to 1730. Newton’s Opticks was his favourite reading matter, and in 1738 he gave up his practice and moved out to Stoke Newington where he built his own observatory. Here, and at Greenwich, assisting Edmund Halley (who died in 1742) he did much astronomical work, and made a unique star-atlas, the Uranographia Brittanica, the plates of which, however, were sequestered in chancery when the printer, John Neale, became bankrupt, and earned quite a reputation (internationally) as an astronomer. When Maskelyne became Astronomer Royal following the death of Bliss in 1764, Bevis, who had hoped for the appointment himself, returned to his medical practice, setting up at the Temple. He was made a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1765. But astronomy got him in the end, for, continuing his studies, he was turning quickly from his telescope one day when he fell, sustaining injuries from which he died. It could only have been at this period of his life, at the Temple, as a F.R.S., that Paine knew him. ‘As soon as I was able I purchased a pair of globes, and attended the philosophical lectures of Martin and Ferguson, and afterward acquainted with Dr. Bevis of the society called the Royal Society, then living in the Temple, and an excellent astronomer’.

Moncure Conway in his Life of Paine mentions that Rickman assigns the period of instruction in astronomy to the year 1767, but that he himself preferred the earlier time of 1757, when Paine would have been 20 years of age. Moreover, he suggests that Paine would have been too poor to afford globes in 1766-7. A study of the lives of his mentors shows clearly that he met Martin and Ferguson fairly certainly at the earlier time, but Dr. Bevis only at the later period, having bought his globes, terrestrial and celestial, ten years previously. On the first occasion he was a staymaker with Mr. Morris of Hanover Street; on the second he was teaching at Mr. Goodman’s and then in Kensington.

There were some important events taking place in astronomy at this time but they seem to have escaped Paine’s notice. William Herschell discovered the seventh, telescopic, planet in 1781. He wanted to call it ‘George’s Star’, but it is now called Uranus. The scientists in Paris would have known all about this important discovery but one supposes that there would have been no occasion to discuss it with Paine; in any case he did not speak French fluently. There had been transits of Venus across the Sun in 1761 and 1769 (the only occasions that century) and Paine mentions them in a footnote to prove how man can know sufficient to predict these and similar events. They must have been occasions of much general public comment — especially when scientists were trying to calculate accurately the distance of the Sun from Earth at these events. And then in 1789, Herschell made his great 40 foot telescope, the envy of astronomers everywhere, indeed, the National Assembly were later to promote a prize for such an undertaking. However, time, scarcity of the necessary metals, and the shortage of money prevented any such project succeeding in stricken France.

Thomas Paine had minimal experience at the eyepiece of a telescope and he showed no inclination later in his life to pursue astronomical studies. But in these brief pages of The Age of Reason he shows he had gained a very clear understanding of the Solar system from those early days in London.

10, Stevenstone Road, Exmouth, Devon, EX8 2EP.