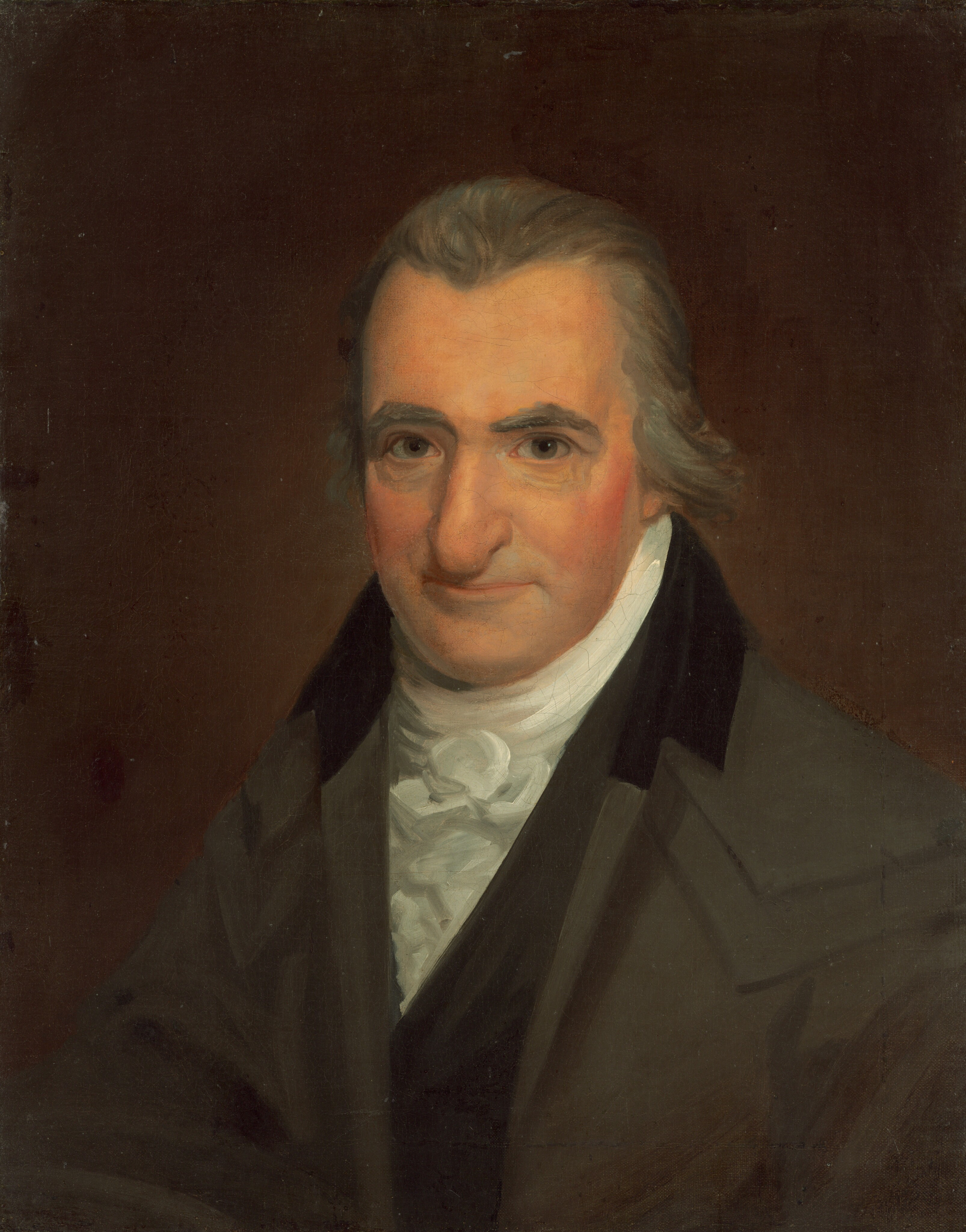

by James Betka

TOM PAINE AND REVOLUTIONARY AMERICA by Eric Foner. ix, 526pp. New York: Oxford. University Press. $13.95.

ERIC FONER HAS GIVEN us a book which is both challenging and provocative. It would overcome the limits of prior interpretations of Thomas Paine with a new understanding of the pamphleteer and his works, trace the “roots” of his political thought and establish the “unique impact” of his writings. All three theses are interrelated and explained through the historiography of a social perspective. Such a formidable tripartite research inquiry should command the interest of every student of Paine and no doubt this work will affirm the prescription.

Viewing the eighteenth century’s most prominent pamphleteer as a voice of rising artisans and “other groups,” Mr. Foner would define Paine’s social context as one dominated by the influence of independent tradesmen and mechanics. Taking cues from E.P. Thompson, he would demonstrate that Paine’s works are better understood and belt appreciated as expressions of support for sociological brethren and associates. Supportive of the artisan thesis is a second which traces “the roots of Paine’s thought in eighteenth-century England” to an ideological context described variously by scholars as a radical Whig tradition, Country ideology, Atlantic Republican Tradition, Opposition, Whig Canon.* Whereas the labels reflect divergent aspects of contemporary English political thought, all illuminate dissatisfaction with political life in England during the eighteenth century. Mr. Foner would prove that Paine, was both a spokesman and product of this dissatisfaction and, furthermore, that such both a spokesman and product of this dissatisfaction and, furthermore, that such research is a suitable base upon which to build a “more organic understanding of the relationship between ideas and social structure.” Mr. Foner’s final thesis is that Paine’s success was”unique” to his time because he had “forged a new political language.” In this respect Paine is understood to have “created a literary style which thus appealed to artisans and which brought his message to the widest possible audience. In support of all the author has generated a trenchant piece of modern scholarship. Profuse in its footnotes, generous in its acknowledgement of substantial advice and criticism, the research draws on primary and secondary sources from both sides of the Atlantic. But in spite of its erudition the work falls on all three counts.

The overriding difficulty with Mr. Foner’s text is his penchant for social history. Paine’s ideas and life, his “new political language,” his ideological origins, have all been sacrificed and appear as little more than window dressing to embellish the author’s fascination with E.P. Thompson’s artisan thesis. Print devoted to the artisans of colonial Philadelphia and to English lower class radicalism consumes substantial portions of the whole and Paine is scarcely to be found (let alone integrated context anywhere. Nor can one escape criticism with an exclaimer admitting that Paine “all too often disappears from the narrative.” After all, we are told this is a book about Paine. Furthermore, although Mr. Foner is sufficiently sensitive to “Old Left” abuses in social history, he appears to have learned but selectively from its critics. Acknowledging that no working class existed in the eighteenth-century he yet ignores the guiding maxim that one ought to choose car – fully among facts so as not to construct the past to ‘fit’ preconceived assumptions – especially those developed in another context. Mr. Foner thus creates his own problems and Paine emerges as a man sympathetic to both Country ideology and the cause of artisans, two rather incompatible perspectives. Paine is made to appear warm to the Country ideology when it supports the Thompson thesis, but when the evidence does not do so it is merely ignored. On yet other occasions, the ideology itself is distorted to fit the artisan thesis and preferred interpretation of Paine’s views. Likewise Paine’s personal associates are selectively emphasized so as to lend credence to the artisan connection. That artisans composed but a small group among Paine’s many associates is not acknowledged and one can only presume the omission is a purposive distortion toward the same end. Thus an internal contradiction between artisans and Country ideology leads Mr. Foner to offer a confusing, and not terribly exciting, analysis by a capricious selection of evidence unable to sustain its stated objectives.

But let us review Mr. Foner’s thesis that would explain “the roots of Paine’s thought in eighteenth century England.” Where is the evidence? The question is not pursued at all, for there is no examination of Paine’s “roots” in English thought other than a cursory account of the political setting of eighteenth-century England. The author contributes no primary research to link Paine with the ideological context of the nation of his birth. Instead Mr. Foner would emphasize that these “roots” – as well as the “nature of Paints republican ideology” – are to be located in a context of rising American artisans. Even if this intellectual sleight-of-hand is permitted, we can discover virtually no discussion of Paine’s republican ideology. Only an examination of the context of republican ideology “rooted” in Philadelphia. I for one am not certain that E.P. Thompson’s thesis developed in an English social context will authenticate a like understanding of the context of Philadelphia. Furthermore, it is a strange form of contextualism which emphasizes an American setting to explain a born Englishman of thirty-seven odd years who began writing from the moment of his migration to the colonies.

The mischief flowing from these internal contradictions is evident throughout the work, but is exhibited most perspicuously in Mr. Foner’s attempt to prove that Paine embraced an “expansion of market relationships in the economy and society” of Philadelphia. He must do so if he is to link Paine to the artisan thesis. But Paine’s views on the tenets of Country ideology do not favour an artisan explanation on this issue. Paine can be either a spokesman of Country ideology or the voice of an artisan viewpoint, but he cannot be both simultaneously because Country ideologues were decidedly ambivalent toward contemporary economic arrangements. An economy dominated by commerce and trade – characterized chiefly by an interest-ridden National Debt, stock-jobbing, rising moneymen, paper currency – had created the same discomfort for Paine as it had for the Country (That modernity can scare observers into adopting radical and reactionary positions is evident when one examines the followers of Country ideology as well as those of Karl Marx). On six separate occasions Paine had referred to the Debt but only once (in Common Sense) did he ever suggest that he supported what today is called deficit spending. Mr. Foner ignores all such commentary, as well as the views of scholars as Isaac Kramnick, and cites in evidence the solitary equivocal statement of Common Sense – thus making a rule out of a dubious exception. I say “dubious” because even in this instance Paine qualified his support by adding that only where “it (a Debt) bears no interest, is (it) in no case a grievance.” The remark was that of a propagandist seeking to encourage colonial separation from England. Was it not Paine’s intention in writing to point out that a Debt might bind thirteen colonies into one and provide an economic means with which to build a new nation and a navy? Did he not qualify his support with the caveat of “interest” (it matters not whether he was referring to capital “interest” or the private “interest” of money-men In government) so as to deny a plague upon the public house? A more serious distortion is the convenient omission of any mention of Paine’s declaration – from the same pamphlet – that trade being the consequence of population, men become too absorbed thereby to attend to anything else. Commerce diminishes the spirit of both patriotism and military defense.

Such are the remarks of a man who favoured an “expansion of market relationships.” Perhaps but let us examine other aspects of contemporary economics attacked by Country ideologues in juxtaposition with Paine’s own statements on such matters and during his long career did he exhibit anything other than antipathy for paper currency? Legislative “factions” seeking their private interests in the form of economic gain? Stock-jobbing? Money-men? Joint-stock and trading companies? Monopolies? The answer is more than negative in that Paine went out of his way to condemn these in all cases. Such are the remarks of a sympathizer favouring contemporary economics. Perhaps but let us examine support for American banks, the second major pillar underlying Mr. Foner’s artisan interpretation of Paine. Long subject of controversy and curiosity, Paine’s defense of the banks does suggest deviation from a tenet basic to the Country posture. Or does it? Is it possible or even likely that Paine’s shifting was essentially contextual (rooted in personal experience)? In other words, that his writings may have been data to awareness of the uniqueness of America’s historical position, to the destructive inflation which ravaged its war economy, to personal experiences in England and America where he learned to distrust paper (commercial or governmental) currency? Could it not be that these contextual experiences led him to conclude that state chartered banks were the only mechanism which might produce sound American currency to combat the aforementioned economic problems? Is it not also possible that a pamphleteer known to have sold his services may have done so once again for yet another good cause?

Finally, if we review the totality of Paine’s writings for evidence of thematic symmetry on those issues included under the rubric of Country ideology, might we not conclude that Paine adhered to its economic prescriptions as part of a more generalized Ideological position? What were Paine’s views, for example, toward standing armies, on civic virtue and political independence of legislators, placemen and pensioners, factions and parties, luxury and corruption, popery, the concept of “Public Good”? In such a perspective Paine’s views on economic matters appear consistent with Country ideology and thus something other than what Mr. Foner would make of them.

That Mr. Foner never resolves his problems of Country ideology versus artisans is apparent in other ways, also. Symptomatic is the assertion that Paine abandoned “temporarily” his regard for “men of commerce,” in the interest of free trade which led to his attack on monopolies in 1778-79. Yet Mr. Foner simultaneously admits this is contestable in noting that support for free trade and attacks on monopolies were not “mutually exclusive” (P.160). What Mr. Foner really means is that such views were mutually supportive but to take such a position would be to damage ‘his’ Paine. Related and symptomatic of the Country-artisan conflict also is a particularly tortured attempt to locate Paine within the dichotomy of old versus modern political ideas. Invariably Mr. Foner would prove Paine was a political ‘modern’ and thus a socially progressive sympathizer of the artisan cause. The assertion is unequivocally Paine’s thoughts are “strikingly modern” and involve a “complete rejection of the past” (p.xix). Yet on the very same page he acknowledges Paine’s uninterrupted commitment to the concept of Public Good – a thoroughly classical (and Country) notion linked to Paine earlier by England’s J.A.W. Gunn, among others. Likewise Mr. Foner documents Paine’s persistent distaste for legislative factions (pp.87-89). Indeed, this was an older, pre-Madisonian political conception, one which was dear to the hearts of Country Ideologues. Witness several among many revealing, If not also equivocal, admissions: Paine was a modern, but “to be sure, be could use the familiar language of the Commorarealthmen” (p.76); “Paine was less attuned.., to the dangers of class conflict in a republic” (p,89); “Paine himself was hardly free from from the tension between the individualist and corporate implications of republicanism” (p.89); “At times, Paine too seemed to embrace this pessimistic view of human nature” (p.90); “A certain tension existed between laissez-faire economics and Paineite republicanism” (p.154); on pp.159-60, Paine is made out to favour the old political “virtue” while not sharing in that Country distaste for commerce which was so destructive of it – contrary to the views of his closest political, personal and nonpartisan associates, Richard Henry Lee and Henry Laurens?

In support of his second thesis, Mr. Foner would reconstruct the social context of Philadelphia to illuminate Paine’s involvement in growing class conflict between artisans and “wealthy” merchants. According to Mr. Foner, it was the artisan who was a prime force for radical change leading to the progressive Pennsylvania Constitution of 1776, who promoted free trade and backed the creation of banks to obtain financial credits. Here again, however, historical construction is undermined by a host of internal contradictions of Mr. Foner’s own making. Take for example the attempt to trace class antagonism between artisan and “wealthy” merchants (and later within the artisan stratum itself). Toward this end Mr. Foner defines Philadelphia artisans as a broad social category which included virtually everyone except merch- ants, labourers and artisan apprentices. That artisans and less wealthy merchants may well have enjoyed common bonds is downplayed; what we describe today as a sense of “upward mobility” fostering social integration (at least in the case of apprent- ices) is similarly avoided. Was Philadelphia’s class structure that rigid, stultifying or pregnant with latent class antagonisms? The major source of conflict is nevertheless explained through underlying economic differences rooted in differing artisan and “wealthy” merchant conceptions of private property. According to Mr. Foner, artisans excluded from their definition of property liquid assets,elegant residence and personal possessions. John Locke or no, does he mean to say artisans failed to consider such elements of their private property – or only that held by wealthy merchants? In yet another intellectual sleight-of-hand (on the very same page), Mr. Foner declares that “the difference between merchants and artisan attitudes toward property would influence many of the political disputes and alignments of the 1770s and the 1780s.” What began as a limited assertion of narrowly defined class conflict now becomes a community-wide social conflict incorporating less-than-wealthy merchants in the class war of artisans. Compounding his problems, Mr. Foner then proceeds to undermine his previous assertion with the observation that it was not always true because an “artisan commitment to private property and business enterprise also pulled artisans into alliance with Philadelphia’s mercantile community.” The conclusive and self-imposed denial of his construction, however, occurs in a discussion of the role of deference in colonial political culture. In his attempts to illuminate a gap between the wealthy and a “third class of socially marginal persons”, Mr. Foner cites the “dependence of most upon urban economic interests on commerce” which encouraged political deference toward the wealthy. The sole reason for calling attention to this remark is to record Mr. Foner’s own admission of a fundamental socio-economic bond “between the wealthiest Philadelphians and the great majority of their fellow citizens.” Whither strategic class conflict in a milieu of overwhelming mutual dependence upon commerce? These seeming contradictions in Mr. Foner’s methodology are ubiquitous. But they do have their advantages. In reconstructing a diffuse, internally contradictory social setting the author thus can explain any political event occurring in that city and state by reference to the artisan thesis. Any political actor or action will readily fit his social description. Whether this is legitimate historiographic license is made more perplexing by the absence of the main character. Where is the articulate political chameleon pamphleteer who allegedly defends artisans against merchants as a class, who completes his work in Philadelphia as the spokesman of merchants opposed to his former allies? Ask Mr. Foner. It is he who makes Paine “disappear” from the narrative.

To explain his third thesis Mr. Foner would prove the “impact” (popularity) of Paine’s works, in part, through the artisan perspective. But lithe “ideas expressed’ were the sentiments of artisans that had greatly enlarged Paine’s audience, this begs numerous. questions. If the artisan thesis is suspect, as indicated above, what does that do to an “impact” interpretation? And even if we accept this assessment are we to believe it was primarily artisans who generated the success of Paine’s works?

Mr. Foner’s examination of Paine’s writings also produced the discovery of a “new political language” and style in a common idiom which assured a “unique impact,”But Paine’s political language and style were “new” and “unique” only to Mr. Foner and those American colonials who had never witnessed the raw aggression and emotional power of English political writers practicing their trade for a half-century prior to 1776. One is inclined to believe a contextualist historian would have sought a connection between Paine’s style and the country which had spawned and matured our pamphleteer. It is less than credible to think that an Englishman of thirty- seven years learned to write and developed a style only after emigration from his laomeland (witness Excise). Where is the linkage between Paine’s style and the count of his birth? Can it be accepted upon examination of stylistic patterns, the philo- sophy and practice of discourse in England, that Paine’s writings exhibit something “new” and “unique”? This flies in the face of virtually all research evidence about discourse in eighteenth-century England. Whether one examines the theory and practice of style in pulpit oratory, academic rhetoric, science, the popular press, political novels, publishing, literature, or belles lettres, one discovers compelling contextual linkage to establish that Paine’s works were distinctly English and either conventional in manner and style. As one authority, Professor Wilbur S. Howell, has documented a “New Rhetoric” dominated all forms of English discourse throughout the century, Where is the style of discourse developed by Bacon, Allikins, Sprat, Locke, Glanville, Boyle, Blair, Smith, Reid, Priestley, E. Witherspoon and Campbell? Promised primary bread we are fed secondary cakes of the late Harry Hayden Clark, Ian Watt and James Boulton. In spite of the fact that information about English discourse is readily available (if not common knowledge), in spite of the fact that the author acknowledges Paine’s “similarities” to England’s novelists (citing James Boulton), in spite of the fact that he concurs with Professor Bailyn that Paine’s language was different from American political pamphlets (p.83), Mr. Foner never locates a context with which to explain the “unique impact” of Paine’s works. What Is peculiar, however, is that Mr. Foner cites a work by Professor Bailyn in which the latter concludes “These (Paine’s sociological circumstances and his ‘violent, slashing, angry, indignant’ language) were English strains and English attitudes just as Common Sense was an English pamphlet written on an American theme.” If Mr. Foner chose to explore this assertion, he has given us no evidence to support such a conclusion. Or was it the case that Mr. Foner chose not to explore such clues because they might yield evidence to question the artisan and unique claims regarding Paine’s style and “new political language.”

It can be observed that there exist numerous minor errors, apparent contradictions and otherwise questionable features in Mr. Foner’s text which suggest poor editing. Use of the same Hogarth print, Gin Lane, to illustrate the life of London’s Everyman, for example, duplicates that of Bailyn’s essay on Common Sense published in 1973. Furthermore, in his references to the excise petition, Mr. Foner merely repeats the mistaken interpretation of others. Examination of the records in the “Customs House Library (sic)” will show the petition was passed on to the Treasury without prejudice. Likewise, it ought to be noted that Paine arrived in the colonies in December, not November, of 1774 (p.57) – as Frank Smith demonstrated conclusively thirty years ago. Furthermore, there was no “federal government” extant in America in 1781 (p.192). Furthermore, Mr. Foner announces that “for the first time” in the 1780s, Paine sought political explanation through economics in uttering: “a man’s ideas are generally produced in him by his present situation and condition” (p.202). This statement of philosophical environmentalism popular in the context of England for at least a century appears unknown to Mr. Foner, also. Worse, the latter errors as to the initial date of this new environmentalism as any reader of Excise can surely attest. Furthermore, it is debatable at best whether Britain’s mercantilist Navigation Acts were as restrictive to Mr. Foner’s Philadelphia merchants as he has suggested (p.25). Most historians conclude that the Acts were not adequately enforced and were also rendered ineffective by colonial evasion. Furthermore, as any student of Paine readily discovers, only his English enemies called him “Tom.” Finally, there is a remark so at odds with the facts that I cannot believe Mr. Foner would assert that Paine’s “view of the Bible was starkly literal and ignored its metaphoric and mythic qualities” (p.247). It was precisely these “qualities” which Paine cited to refute biblical argument and the prophets of the Old Testament.