By George Hindmarch

The meteoric political career of Thomas Paine was so dazzling that it has largely eclipsed the events of his formative years during which he obtained the expertise and developed the tenacity that enabled him to respond to the opportunity afforded by the rapid changes in the American colonies in the years following his arrival there. Paine’s biographers have usually given a brief account of his early years and his excise career as an introduction, but one treated as a closed date separated from the main events of his life by his migration to America. There has been little attempt to fit this early period into the overall pattern of his life, and his first thirty-seven years have often been spoken of as a period of failure. In the opinion of the present writer, this is a mistaken view.

Admittedly there are great difficulties in evaluating his early struggles for Paine was very reticent about personal matters, and other sources of information are not easily tapped or understood. Yet they are informative, and it may be because of the neglect of material relating to these early years that Paine’s character and the influences that bore upon it have not yet been fully comprehended. Oldys, although a hostile biographer, was under no illusion as to the importance of Paine’s excise career, and took full advantage of his exceptional opportunity for tracing details still available to him in the official records. Moncure Conway, almost certainly the greatest of Paine’s biographers, played the major part in rescuing Paine from the obscurity in which his enemies sought to bury him, but Conway paged himself under some difficulties regarding the excise period by retiring to America to write his life of Palle, for unlike Oldys he was thus without contact with practical excisemen who could have informed him about working conditions in the excise, which have changed very little over the centuries; they could also have explained to him that the excise has its own jargon and words may be used in an excise context to convey something quite different from their meaning in common usage. Conway did not underestimate the importance of the early years, and went to great pains to check Oldys and repudiate some of his slurs, but in his desire to redress the Injustice done to Paine he was at times in danger of doing Paine even greater damage, and this danger has not been lessened in the long run by the attempts of Palm’s later biographers to explain Paine’s excise dismissals without studying the excise background and language in sufficient detail to express the facts accurately.

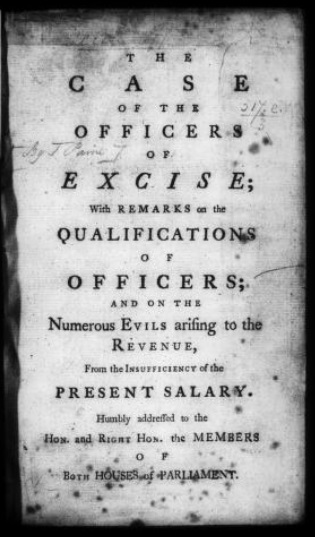

It is disappointing to note that some of the best recent accounts of Paine’s life are quite sloppy in their presentation of his excise career. It is necessary for an understanding of Paine’s development to stress that he was an Excise Officer, never a Customs Officer, and in The Case of the Officers of Excise he differentiated between Excise Officers and other revenue officials. Not only were the Customs and Excise separate revenue services, but there was rivalry between, and friction was so acute on some occasions that special rules were drawn up in 1755 to minimise it when representatives of the separate services became involved in a particular investigation at the same time. It was not until 1909, a hundred years after Paine’s death, that the Customs and the Excise were brought together in the newly constituted department of Customs and Excise, and this event is of interest to students of Paine because it occasioned the disgorging from the archives of the Inland Revenue in Somerset House of hundreds of volumes of excise records which till then had been regarded as confidential and not available for inspection. These books are almost wholly headquarters records which are only partially representative of the work of the excisemen, for the vast bulk of the department’s work was performed by local officers usually working as individuals in near isolation from their fellows. Paine was such an individual country officer in his two periods of service in Alford and Lewes, and his personal records would have been kept in the offices of senior area officials known as Collectors.

Few local records have survived, or at any rate have yet been brought to light, but such as are available to us, although Incomplete, are of great importance in any consideration of Paine as an Exciseman; yet they have been entirely neglected. Not only have his departmental efforts been incompletely comprehended, but the rather curious fact that he chose to be an exciseman, and clung to his appointment, does not seem to have excited the curiosity of his biographers to when it might well have afforded a challenge. For the Excise was a service which attracted a phenomenal amount of hatred from the public, and this hatred is again an important element in Paine’s story which has not been fully taken into account.

The subject of the Excise is undoubtedly a difficult one, for whereas there have been a number of accounts of the Customs department – for which more comprehensive records survive – the Excise has been almost entirely neglected by serious historians as a subject in itself, and it will now be every difficult task to fill this glittering gap in the history of central government. In addition to the paucity of early Excise records there is a rather major difficulty in that the individual officers and the staff at headquarters have been, until the last decade, quite separate castes within the department knowing very little about each other’s work. Yet the Excise has exited such extraordinary reactions from the public at large that it might have been expected that social histadens would have queued up to study it. The redoubtable Dr. Johnson laid down the tone in characteristic and provocative fashion when he defined excise in his famous dictionary as a hateful tax levied upon commodities, and adjudged not by the common judges of property, but by wretches hired by those to whom the Excise is paid. On the appearance of his dictionary, the outraged Excise Commissioners took legal advice, and the Attorney General optioned that there was libel, but he suggested that an opportunity for changing the words mould be allowed, but Dr. Johnson did not deign to take action and apparently the Commissioners did not dare!

Some general observations appear necessary if the excise background to Paine’s

activities is to be appreciated.

The range of duties discharged by excise officers is very wide and complex and it extends far beyond the narrow field generally regarded as appropriate to a minor civil servant; but in its simplest form – the collection of tax on consumable articles such as alcoholic beverages – it has been in continuous operation in England since 1643. Before that date excise had often been employed on the continent where its operation had led to its acquiring such an evil reputation in England that any known consideration of its introduction led to a public outcry. Both Elizabeth I and Charles I are known to have thought about it, but each shrank from the probable consequences of public resentment. Even after the outbreak of the civil war when the parliamentary forces stood in need of increased financial resources, a statement was issued in 1641 which not only denied that imposition of the excise was imminent, but declared that those spreading the rumour should be sought out and brought to the House for punishment.

Yet in 1643 the excise was introduced, allegedly only for the duration of the civil war, at first in the simple form of a levy on popular alcoholic beverages to raise revenue for the support of the parliamentary forces; it was collected by eight Commissioners and their subordinate officers, who were empowered to call upon the assistance of organised forces if necessary. London was a stronghold of the parliamentary cause, but its citizens nevertheless saluted the imposition of the hated excise – which taxed the poor man’s glass equally with the rich man’s – by rioting and burning the Excise House which had been established at Smithfield. The royalists also imposed excise on the areas they held and also found it expedient to pretend that it was a temporary measure. But although the range on which excise was imposed was in due course reduced, the excise has never been revoked, although resentment against it continued and sometimes flared up in riots.

So great and so persistent was the general hatred of the excise that in 1733 when Walpole introduced a plan to extend it, he was forced by fierce opposition to withdraw his Excise Bill. Yet Walpole had good grounds for his proposal, for the customs service had been found to be both inefficient and corrupt (150 Customs Officers having been dismissed in the preceding few years for fraudulent practices) and it made sense to transfer much of the control of imported dutiable good to the Excise. Contraband goods were being widely and frequently landed in quantity, and distributed throughout the country by organised gangs of armed smugglers who rode with impunity to within a few miles of London in such strength that revenue officers did not dare challenge them without military support. Once these goods had passed out of the coastal areas the excise officers would have been much better placed to challenge and collect duty at a later point of sale.

The cancellation of Walpole’s excise proposals led to widespread public rejoicing. Walpole is reported to have said that his Bill could only have been operated by an armed force and that he would rather resign than enforce taxation at the cost of bloodshed. London celebrated his defeat with illuminations, bonfires, and the ringing of bells. Provincial cities followed suit as the news was brought to them by special messengers. In Bristol the church bells began to peal at 2am and continued all day as bonfires were lit and effigies of Walpole and an exciseman were burnt. Chester never had so many bonfires – one was kept burning for five days – and at Oxford jubilant crowds urged on by the gownsmen of the university rampaged in celebration for three days. More than fifty years were to elapse before it was dared to introduce new excise duties on commodities of general consumption, and during that half-century of hatred Thomas Paine grew up, entered the Excise, was twice dismissed, and emigrated to America to speed the secession of the American colonies.

The distinguishing feature of the Excise has always been the close direct association of the officers with the traders they control for revenue purposes all over the country. Excisemen have never been faceless men, and they are known personally and as personalities in their working localities; and as they were denied employment in their home areas they always appeared as intruders in the eyes of the local people. Their work consisted mainly in visiting traders’ working premises, keeping permanent accounts of the traders’ business operations, and ensuring that all relevant excise dues were collected at the appropriate times, When notices had to be delivered to the public at large, this was done, even in Paine’s day, by affixing them to the doors of churches, and adding a notification of the official residence of the excise officer for the area. The faceless men of the service were the Commissioners at the Excise Office in London who disdained to deal directly with the public, with whom until 1838 they would not communicate otherwise than through their local officers. The Commissioners have ruined extremely chary of placing their signatures to documents which woul. indicate their personal cognisance of contentious matters, and still prefer to shelter behind lesser officials and irregularities such as any misrepresentation of legal provisions are brought to their notice – even though the representations may be upheld and the incorrect practices rectified as a result of such submission.

In 1771 the total strength of the Excise department was 4,321, of which the headquarters of 9 Commissioners and their staff comprised merely 230. Country excise officers totalled 2,736 under 256 Supervisors reporting to 53 Collectors, who were the Commissioners’ representatives in the provinces, each Collector being responsible for an area approximating to a county. Communications were very poor by the standards of today and the Collectors were vested with great authority so that swift action could be taken when emergencies arose but the conferring of local authority also presented risks, as a Collector could act to conceal irregularity as well as to suppress it, and Collectors proved on occasion to be fallible mortals. There were also hundreds of town officers in London and the ports.

Supervisors themselves needed to be supervised, for they not infrequently abused their authority, and officers were poorly placed to resist improper proposals or rebut malicious charges made against them if they declined to co-operate with a dishonest Supervisor. These matters will call for greater consideration when considering Paine’s two dismissals, which are outside the scope of the present article, but in passing it can be observed that in 1725 the Commissioners commented that few Supervisors showed proper diligence and ordered the Collectors to report on them. Supervisors were forbidden to borrow money from officers as some neglected to pay their debts, and they were forbidden also to make arrangements for participating in officers’ rewards when they had not shared in the officers’ work that had earned them.

It has always been known that Paine was active in promoting a scheme for obtaining an increase in the salaries of the excise officers. Oldys comments that Paine had ‘risen by superior energy to be a chief among the excisemen,’ and also remarks, a ‘rebellion of the excisemen who seldom have the populace on their site was not much feared by their superiors.’ It has usually been taken for granted that Paine’s initiative on salary drew upon him the displeasure of the Commissioners, but this is not established, and examination of the official records has produced evidence to the contrary, during the period when the claim he had submitted in accordance with the procedures of the times was under consideration.

The Commissioners had long been concerned about dishonesty and irregular cond- uct in the excise service, and not only Supervisors but also officers and Collectors had been guilty of misdemeanours which had incurred the Board’s administrative displeasure. There had been a number of cases of officers collecting excise dues from traders, and simply making off with them; these blatant thefts had not been hushed up, but on the contrary the Collectors had been instructed to warn traders against paying excise dues to officers and to tell them that in any case of an absconding officer the tax was still due to the Crown and must be paid to the Collector. In 1761, it was ordered that traders were themselves to collect their excise licences which were not to be delivered to them by officers, who presumably may have thought that such a service deserved pecuniary reward. But probably the most significant warning was that issued in 1743 when the Commissioners circulated all the Collectors and ordered that every officer and Supervise should write into his records a stern admonition against entering and searching private premises without first obtaining a warrant authorising entry from the Justices of the Peace. The order makes clear that many warnings to the same effect had been previously issued, but they had been ignored, and quantities of goods had been illegally seized by officers on unjustifiable suspicion that they had been improperly obtained. There is no reasonable doubt as to the root of these malpractices. The officers had long been unable to support their families and themselves properly by the honest execution of their onerous and dangerous duties, and had frequently descended to augmenting their official salaries by irregular proceedings, to the severe embarrassment of the Commissioners and the detriment of the reputation of the excise service.

No student of Thomas Paine can imagine that he would have viewed with equanimity these abuses which went on around him, and which the Commissioners themselves repeatedly brought to the notice of every working officer. Paine a reformer by nature and a preacher by inclination, could have seen no course open to him other than to work for the eradication of these irregularities and the creation of an honest excise service which would operate efficiently and humanely to the eventual good of the community, to whose ultimate benefit the excise revenue should properly be used. Nor would the excise service of his own time have been his sole concern, for much greater issues would already have been revolving in his mind.

In 1772 Paine reached the age of 35 years. He had spent his life till then in a variety of ways, and (he told Rickman) he seldom passed five minutes of life without acquiring some knowledge; he had acquired a wealth of acceptance in town and country, on land and sea, as staymaker, sailor, preacher, schoolmaster and exciseman. He would then have been meditating the schemes of social welfare which he was to publish in his Rights of Man, and which we know from his correspondence he discussed in his London days with John King in the city. Paine was no mere dreamer, he actively pursued the realisation of his ideals, and as well as formulating plans for old-age pensions and the like he would have been considering how they might be put into operation in the England of his day when nationwide services were nearly non-existent and local services in their infancy. The Excise, and the Excise alone, operated a network which covered every square inch of the kingdom, and no matter where any state pensioner might reside, his address would already be allocated to an Excise Officer who would accept responsibility for any business of state related to the occupants of that address. Already some of the work of supervision of pensions, such as those paid to Chelsea Pensioners living away from the hospital, had been delegated to the Excise – indeed dishonest excisemen at Stirling in Scotland had been sentenced to transportation for fraudulent practices in connection with these pensions. Had a national old age pension been introduced in Paine’s day the Excise Officers would have been called upon to help operate its provisions, just as they were in fact called upon when the national scheme was actually introduced in the 20th century. The excise service was the only existing means of ascertaining and catering for the needs of the distressed sections of the populace as well as being one of the chief means of raising the necessary revenue. And throughout the whole kingdom there was probably no man more keenly aware of the potential value to the community of an honest efficient excise service than Thomas Paine.

In Paine’s day no ordinary man could have envisaged that a single Excise Officer could set about putting right the deficiencies in the Excise, but Paine was no ordinary man, and he applied himself to provoke the winds of change. In 1776 when he published Common Sense, the world realised his potential for reformation. In 1772 the excise authorities had already made the same discovery, but it was never made public knowledge. At the same time Paine somehow bridged the yawning gulf between town and country, between the mighty Commissioners who sat aloof in London and the thousands of excisemen who performed the routine work of the department in obscurity and near isolation. How he accomplished it we do not know, but he spent the winter of 1772/3 in London working on his scheme for securing an increase in the salaries of the excisemen. Yet he could not have gone to London without the knowledge and approval of his superiors, for unauthorised absence from his station speedily resulted in the dismissal of an exciseman, and we know that Paine was not dismissed for the second time until 1774.

The Excise Office, the seat of the Commissioners, was situated in Broad Street In London, and so was the Excise Coffee House, from which on December 21, 1772 Paine addressed his famous letter to Dr. Goldsmith, which still survives amongst Goldsmith’s correspondence in the British Library. The juxtaposition of the. two similarly named premises is not to be wondered at, yet again the fact that Paine wrote from a coffee house near to the excise headquarters has not apparently called forth comment. Coffee houses were a feature of London life, and they performed more functions than merely to entertain and refresh those who frequented them. There Is nothing unusual in business being discussed in places of refreshment over working lunches or cups of coffee in any age, but the coffee houses of old London were sometimes used as regular offices for business; for example in 1714 when the London Custom House was seriously damaged by fire; the Customs Commissioners set up temporary premises at Ganaway’s coffee house, from which they conducted the business of the Customs department.

The present writer no seriously suggests that during the summer of 1772/1773 Thomas Paine was working on his Case of the Officers of Excise from the Excise Office itself, or its environment, with the active co-operation of the Excise Commissioners who facilitated his efforts. However, as Paine was working in an unofficial capacity – much as present-day representatives of civil service staff organisations work in government offices by arrangement he would not have been allowed to address himself to his colleagues and prominent citizens of the realm from the Excise Office, and so would have adopted the practical expedient of corresponding from the nearby coffee house, whose name would have indicated to all his correspondents that the country exciseman was conducting his salary claim manoeuvres from a command post adjacent to the central authority.

We know from the Goldsmith letter that upwards of 500 pounds was raised by Paine at three shillings per head, and this indicates that the vast majority of his colleagues actively supported him, although individually they were very vulnerable to the displeasure of their superiors. It is most unlikely that such extensive support could have been forthcoming nationally in the England of that day when national trade union activity had never previously been practised, unless there had been some indication that Paine, the chief instigator of the scheme, was working with the cognisance and tacit acquiescence of the Commissioners; it is probable that many excisemen would have declined to append their names to a national petition If there had not been some indication of at least a blind eye from the departmental disciplinarians, for not all excisemen had, or have, the moral courage of a Thomas Paine.

Even in the 20th century organizations of any national body of individuals kept together by central correspondence know the onerous nature of the work involved in securing multiple support for a petition, however worthy its object. Picture, then, the problem facing Paine when without the facilities of the modern postal services he addressed himself to every parish in the country. No register of local excise offices of Paints day has survived, none is known positively to have existed. Examination of the surviving excise records shows that the Channel of communication to them from the Excise Office was through the 53 country Collectors. It is suggested that only the use of the same channel with the tacit approval of the Commissioners could have permitted Paine’s association of excisemen to be formed on a subscription basis.

There is further circumstantial support for this suggestion. Although Paine does not say so in his letter to Goldsmith, his association covered all the excisemen in England and Wales, but not those in Scotland, although the Scots would have been just as sympathetic to his objectives and are unlikely to have been more timid in supporting him than their southern colleagues. The practical exclusion of the Scottish excisemen is apparent from the examination of the official records of this matter which have survived and have now become known. It is not difficult to understand why the Scots were not included in Paine’s petition. On the union of England and Scotland in 1707, five Scottish Commissions were appointed to form a Scottish Excise Board to control excise in Scotland separately from the English excise, but on the same lines, the British revenue being paid over to the English Board for onward transmission to the Treasury. There would therefore have been no direct avenue from the London Excise Office to the individual Scottish officers open to the English Commissioners, or to Thomas Paine if he was using the official channel. The co-operation of the Scottish Commissioners would have been necessary.

Examination of the official records lends further support to the theory that Paine’s efforts did not initially meet with disapproval. It was not of course a new development for an increase in salary to be sought, what was new was that a national body of lowly civil servants, individually obscure and without influence, should be organised in a common application. For those government servants who had access to the corridors of power and knew the acceptable forms of application there was an accepted procedure for seeking increases. Some years before Paine petitioned on behalf of the whole body of excisemen, a single individual in the excise headquarters made his own approach, and in the year of Paine’s petition the six judges of the Scottish Court of Judiciary combined in a common application for themselves and their retainers who went on circuit with them.

The eminence of the Scottish judges and their undoubted knowledge of procedures acceptable to their paymasters, ensure their application of pride of place as a criterion for assessing the technique practiced by Paine. The judges addressed themselves to the Head of the Court of Judiciary in Scotland, the Duke of Queensbury and Dover, and set out the difficulties which changing circumstances had inflicted upon them. We cannot doubt that they would have presented an eloquent and convincing case, and indeed the duke in his subsequent letter dated October 6th., 1773, addressed to the Lords of the Treasury, confirmed this. Unfortunately, as he did not attach a copy of their submission to him we are not able to compare their presentation of their difficulties with that Paine prepared of those of the excisemen. The duke proved a worthy advocate, and although the judges had foreborne to specify the amount of increase in their salaries which might meet their case he recommended that their existing salaries be raised from £200 to E300, with a further £50 on their expenses for earn of their circuits, together with commensurate increases for the clerks, macers and trumpeters, who accompanied them on circuit.

Within the Excise Office, the clerk to the Comptroller had previously made his own approach to the widespread problem of an inadequate salary, and like the excisemen he addressed himself to the Commissioners, his commencing salary in 1741 had been £120 which had been augmented by £60 in 1752; his further petition for relief was undated but the Commissioners forwarded it to the Treasury on October 23rd, 1764 with a recommendation for a further £20 a year. The Treasury warrant authorising this increase bore the signature of Lord North.

The pattern of approach is clear, and it seems that Paine, the countryman from Lewes, was able to learn it, possibly under the guidance of George Lewis Scott, the Commissioner with whom he was able to achieve a considerable degree of rapport – in itself a remarkable feat far an obscure underling, which has also escaped informed comment. Yet the task Paine had set himself was vastly greater than that faced by the Scottish judges in combination; he spoke not for a hand but for more than three thousand, not for eminent members of a highly-regarded profession but for detested and lowly officials. The Commissioners may well have sympathized with his objective but they lacked his courage. We cannot accurately date his presentation to them of his Case of the Excise Officers – which Oldys tells us first attracted the attention of George Lewis Scott – but it is most improbable that the Commissioners did not see it before Goldsmith; it may be that Scott was one of Paine’s superiors who advised him to proceed with the printing and presentation of 4,000 copies. It may also also have been that the Commissioners hoped that Members of Parliament would have the courage to recommend the hated excisemen to the paymasters in the Treasury, but if so they were disappointed and the matter returned to the Commissioners’ table.

Paine told Goldsmith of a petition having been circulated throughout the kingdom and signed by all the officers; possibly this was passed to the Commissioners of Excise, for it could hardly have been addressed to any other authority. It has not been discovered. What has come to light is a short address to the Commissioners over the names of eight excise officers who presumably made up the executive committee of Thomas Paine’s association. It is a remarkable document which has both grace and charm in its presentation. It is not possible to do justice to it by merely reproducing its wording, which is as follows:

To the Honourable the Commissioners of Excise,

The humble and Dutiful Petition of the Officers of that Revenue Sheweth,

That We the undermentioned Persons being deputed by the whole Body of the Officers of Excise throughout England and Wales to represent and set forth in an humble and dutiful Petition the Distress and Poverty we at present labour under, and to Pray Such Relief as the Wisdom and Goodness of That Power in whom the Right of Relieving Us (as Officers of Excise) is vested Humbly beg leave to lay before this Honourable Board —THAT the amazing una increasing Difference in the Price of all the Necessities of Life between the present Time and that wherein the Salaries of Officers were at first established has so reduced the Circumstances or your Petitioners and so involved them in Want and Misery that they are become unable to support themselves and Families with that Credit, Decency and Independence which is essentially necessary in a Revenue Officer.

That our Salaries after Tax, Charity and Sitting Expenses are deducted amount to little more than FORTY SIX POUNDS per annum. That the greatest part of us are obliged to keep Horses purchased and kept at an Expense which we are unable to support. That the other Part are confined to live in Cities and Market Towns, or in London, where the Rent of Houses, Taxes thereon, and every Article necessary for the support of Life, are procured at the dearest Rates That the little we have for our Support is rendered less comfortable by our being removed from all our natural Friends & Relations, and thereby prevented in all those Parental or Friendly Assistances from them, which if enjoyed would in some measure lessen the Burden of our Wants.

Suffer us therefore Honourable Sirs in behalf of our Distressed Brethren and selves to Petition You to take into Your Consideration the Wants and Misfortunes of your Petitioners and to give such Recommendation of their Case to the Right Honourable the Lords Commissioners of His Majesty’s Treasury, or any such other Assistance as Your Honors in Your Wisdom and Lenity shall judge proper for the Happiness of the Petitioners.

And Your Petitioners as in Duty bound will ever pray.

There followed the names of eight brave men to whom belongs in all probability the honour of having launched the first national collective pay claim for working men in the Western World: Thomas Sykes, William May„ Henry Holland, Thomas Gray, John Crosse, Richard Ayling, Thomas Pattinson, and lastly the chief instigator or the petition and godfather of country-wide Trade Unionism as well as of the United States of America, Thomas Paine.

It Is not known how many or the Excise Commissioners were actively in favor of Paine’s initiative; George Lewis Scott, by virtue of his special relationship with George III may well have exercised exceptional influence on the Board, but we know that he could not carry his point without support from other Commissioners. There is however no doubt whatever that all the nine Commissioners united in passing on Paints petition to the Treasury, for on February 5th., 1773, the following submission was forwarded over the signature of every one of them, each signing in order of seniority on the Excise Board:

To the right honorable the Lords Commrs of his Majesty’s Treasury

May it please your Lordships.

We beg leave to acquaint Your Lordships that a petition has been presented to us by several Officers of Excise on behalf of themselves and the whole Body of Officers of Excise throughout England and Wales praying us to take into Consideration their Distresses arising from the Smallness of their Salaries and praying relief.

The Object of this Petition being of great and extensive Importance We have not thought proper to some to any determination thereupon until we have laid the same before Your Lordship a copy of the Petition is therefore annexed to our Memorial which we humbly submit to Your Lordships Consideration.

Excise Office

London

5th, February 1773.

We are Your Lordships most obedient and most humble servants.

The fourth signature of the nine Commissioners is Geo. L. Scott.

By an accident of history, the Treasury did not at that time copy its correspondence into registers (as did the Excise Commissioners), but simply put the documents away. To this chance we owe the fact that the two documents detailed above survived and were passed in due course to the Public Records Office, where they were unearthed by the present writer. It is an interesting experience to look through the boxes of documents handled by the Lords Commissioners of the Treasury two centuries ago. The various petitions have been penned in a variety of hands, and while there is an even tenor of humility in all the missives – those signed by the Excise Commissioners equally with that of the Excise Officers – there is great variety in the present condition and in the style of execution. It does not take long before the missives from the Excise Office can be picked out at sight, for they are beautifully written by penmen who clearly took great pride in their handiwork, and they used excellent materials which have scarcely faded in two hundred years.

Amongst the documents dispatched from the Excise Office to the Treasury none has been seen that surpasses in elegant penmanship the copy of the petition of the eight excisemen. It incorporates elaborate flourishes, multiplicity of capitalized gradations in the size of words and letters which give emphasis and promote some initial letters to semi-capitals. The two associated documents have lain in close contact for so long that the ink of one has faintly penetrated the surface of the other. The two epistles are strikingly similar in style, and both survive in excellent condition except for wear at the edges where they have been folded, and it is noticeable that the folds of the petition are much more worn, as if it has been unfolded for perusal many more times than the Commissioners’ memorial. There are points which provoke speculation. For example the copy of the petition is very large, approximately 15″ by 20”, which makes it a rather cumbersome enclosure In correspondence, and it could easily have been copied in smaller format (it is indeed copied on a smaller scale in the copy retained in the records of the Excise Office). The memorial of the Commissioners is comparatively unimposing in size at about 10” by 15″; one might have thought that the Commissioners would have pref- erred to have their signatures on a more impressive document, and it appears that the copyist may have prepared a replica of the petition, rather than a mere copy of its wording.

However there is another possible explanation. It would have been very time consuming for a single petition to have circulated to 3,000 individual officers for perusal and signature, and it would have been far more practical for a number of separate copies of the proposed petition to have been circulated, say one for each of the 53 country Collections, with supporting sheets on which the officer; could have placed their signatures. In return these separate copies could have been gathered into the composite petition for submission to the Excise Board; it could have been one of these circulated copies which the Commissioners detached and forwarded to the Treasury. This would account for the greater wear which the copy petition appears to have had, compared with the Commissioners’ memorial; had the two documents been prepared and forwarded at the same time, it is likely that wear on their folds would have been similar.

Multiple copies for circulation to Collections would also be consistent with the separate letter concerning the Nottingham officers, which Oldys – with his exceptional facilities for inspecting the official records – discovered. It appears that the Nottingham officers reacted as a group, probably as a Collection group, and this could follow from an approach having been made to them as a group with a copy of the petition. It could have been that the Collector Nottingham was a particularly severe disciplinarian, and that his volunteers did not care to petition with their colleagues without Lurtner assurances from Paine about non-victimisation. Had such been the case, Oldys would not have been anxious for the full facts to be made public knowledge.

While the Excise Commissioners had been happy to recommend an increase in the salary of their comptroller’s clerk they did not dare to recommend one for the Excise Officers. Perhaps in passing on the petition they went as far as was to be expected of servile bureaucrats. By the criterion of the Scottish judges award, the excisemen merited an increase of at least £25 on their meagre £50 per annum, but for 3,000 excisemen this would entail an increase in the salary all of £75,000 – a far larger sum those days than now. The memorial from the Commissioners reacted to the Treasury on February 5th, the day it was dated; perhaps they were called to a discussion for they were regular attenders at the Treasury, but the decision was reached in four days and endorsed on the reverse or the memorial in a significant word: ‘Nil.”

The Treasury’s decision was perhaps a political one, for or the justice of the claim can have been no doubt, as the Excise Commissioners’ words of transmission indicate. Ironically, the excisemen, led by Thomas Paine, one of the greatest democrats of all time, were possibly baulked on this occasion by the reputation of the very people who were to enthuse over his philosophy in later decades. The crowds who poured from the slums of Lennon to defeat Walpole’s Excise Bill in 1733 were active participants in the political scene throughout the 18th century, and their appearances were dreaded. The eleven days discrepancy in the calendar broke them out in 1751, and they rioted in support of John Wilkes more than once. Was it to be expected that they would have remained passive in their hovels if the hated excisemen had been aware of a considerable increase in salary at public expense? These men, whose drink was taxed by the excise, and whose tempers and camaraderie brought them into the streets in unkempt battalions when their sentiments were outraged, haunt the London scenes painted by the contemporary artist Hogarth. A few years later in 1780, when they took to the streets again to terrorise the capital during the Gordon riots, the Lords Commissioners of the Treasury nag well have congratulated themselves that in 1773 they had not risked the Treasury being burned down as the Excise Office was burned in 1643, and as Newgate Prison then flamed before their eyes.

The Excise Commissioners would doubtless have been given an explanation of the rejection of the excisemen’s petition, and it may have fallen to George Lewis Scott to retail it to Thomas Paine. If the reason herein suggested – the unwillingness to provoke the people again with the excise issue and invite retaliatory riots – was indeed the reason given him, then doubtless it would also have been made clear that Parliament would take the same view, and this would account for the cessation of Paine’s parliamentary initiatives Paine would have returned to normal duties at Lewes a wiser and vastly more experienced men, and his valiant spirit even in his disappointment would already have been seeming another path towards the reforms he intended to achieve.

Enough is now known about Paine’s endeavours in 1772/3 to establish that his efforts on behalf of the excise service were gallant indeed, and supported in some degree throughout the department; that his striking achievement in rallying his comrades into a national association has been so little esteemed is surprising. Twenty years were to pass before the stage was set by his Rights of Man for a second round in the battle to secure better representation of working men at the tables where salaries and working conditions were determined. Nor did the second stage meet with swift success, yet success in considerable degree was to come. Is the second stage considered a struggle that failed? If not, can the first stage be considered a failure when at his initial effort Pain’s petition was passed through the established bureaucratic channels to the fountainhead itself, the Lords of the Treasury? This writer suggests that the word failure is inappropriate. Paine’s brilliance in 1773 was recognised by Commissioner G.L. Scott, who remained a Paine supporter, and it would have been a major cause of his recommending Paine to Benjamin Franklin. Franklin in turn would have heard the full story of Paine’s efforts, and would have recognised his striking ability to rally dispersed unorganised men into a cohesive national body by the power of the written word. Franklin by then was well aware of the coming need of a man of Paine’s genius in the American colonies. Without The Case of the Officers of Excise there would have been no Common Sense and the Crisis.

The field is now open to others to discuss and evaluate the facts and opinions set forth in this article, and following the bi-centennial year of American Indep- endence it is not an inappropriate time for such a discussion. Meanwhile a document lies in the archives of the Public Record Office which is basic to the genesis of trade unionism and perhaps also to that of the United States of America. That it is worthy of exhibition is a view the present writer has already expressed; it may be that further support for this view will be forthcoming.

Members of the Thomas Paine Society will appreciate that n new’discoveries, such as the documents described in this article, can only be appraised over a consider- able period of time. There can be a number of aspects of their impact which may need to be carefully considered. Pain’s efforts of 1772/3 may not be easily placed in the evolution of national trade unions for example; so far as preliminary enquiries by the present writer have shown, the early activities previously known were of local associations of working people, who would have been in personal contact. Paine’s association of excisemen was a vastly more difficult enterprise to originate in view of their national distribution and the very small numbers in a particular provincial town.

It will also be appreciated that examination of the old excise records continues, and while no complete account of the true facts of the excise career of Thomas Paine is now likely to emerge in positive form, circumstantial evidence is still being discovered which can be used for the intelligent reconstruction of a much fuller account of his activities and their effort upon our national social history, than has previously been made public.

The writer of this article hopes to be able to make further contributions to our knowledge, and perhaps to compile a much more ambitious study of Thomas Paine as an exciseman, as it remains his opinion that the excise influence was not only of major importance in forming his exceptional character but that it remained with him and played a considerable part in his activities long after he had been forced out of the excise service.

NOTE:

The documents transcribed in the body of this article are made known by Mind permission of the Keeper of Public Records, to whom is delegated authority to administer the copyright in them which is the property of the Crown.