By Christopher Brunel

Testaments Of Radicalism Of Working Class Politicians, 1790-1825. Edited with an introduction by David Vincent. Europa Publications, £7.

David Vincent in his introduction refers to the quite unprecedented circulation in the 1790s of Thomas Paine’s Rights of Man. Its dangerous truth; in explaining the corrupt state of the British government, provoked a response from the political and religious establishment, that, when it could not denigrate and twist the activities of the radicals, threw a blanket of silence over them. Only in recent years is Paine emerging again into the sun.

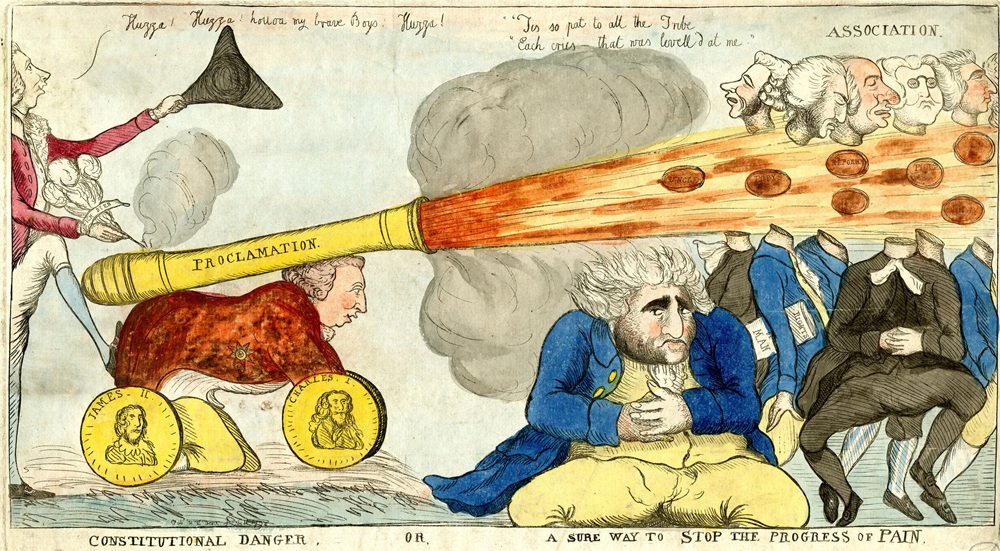

After the turbulent 1790s, access to and the use of the means of publication (writes Vincent) became a central component of class struggle – a cannon thread in virtually every campaign was the hostility to the treatment the working class received from the contemporary press.

This book presents five autobiographies of working class politicians, spanning the period from the crisis over the American Colonies to the threshold of workers discovering Marxism. They told it like it was, and so the memoirs for invaluable correctives to bourgeois histories. Because their stories were feared by the ruling class, the authors have not yet become household names.

They are Thomas Hardy, Piccadilly shoemaker (not the author) and founder of the London Corresponding Society; James Watson, compositor, freethinker, Owenite and Chartist; Thomas Dunning, another shoemaker, trade unionist and Chartist from Nantwich; John James Bezer, Spitalfields Chartist; and Benjamin whose career bridged half a century of political activity and co-operative work in Halifax.

Fascinating as they are in their varied styles and different periods, all that they deal with, the memoirs are only fragments of our history. They are especially useful, though, in understanding the roots, from which the labour movement developed. In addition to the events they recount, It is the flavor that the five authors give that helps us to understand the struggles of our political forefathers. The least imaginative of us is immediately put in their shoes.

!n Hardy’s autobiography we can understand the appropriateness of his handy language: he writes of the intrepid martyrs of freedom, “that patriotic band broke the ruffin are of arbitrary power, and dyed the field and the scaffold with their pure red precious blood, for the liberties of their country.” Hardy’s home was raided at 6:30 one morning in 1794, he was thrown into the Tower of London, and his wife died in pregnancy soon after; his treason trial lasted nine days “by the unanimous voice of as respectable a jury as ever was ever empanelled he was found not guilty.

James Watson in the 1830s was imprisoned in Dorchester and Clerkenwell prisons for selling radical end freethought literature. He summarises his memoirs as having one object alone – “to Show our fellow workmen that the humblest amongst them may render effectual aid to the cause of progress if he brings to tho task honest determination and unfaltering perseverance.”

Thanes Dunning includes an account of organising the defence of two men arrested for Trades Union activity. One was quite illiterate and the other “A light minded, dancing, public house man” – a brace, as Dunning tells us, of very awkward clients. Like thousands after them, Dunning and the comrades rally round; the case was no landmark in trade union history, but the style of operating – reading as an exciting adventure, yet with high and serious stakes – is almost classical In showing that the pioneers knew how to organise.

In racey style, J.J. Bezer describes his youth and the grinding poverty he suffered in London. At Clerkenwell Green he first learns of Chartism, and hungry in a land of plenty, for the first time seriously enquires “WHY, WHY – a dangerous question…isn’t (sic) it, for a poor man to ask.” There Bezer’s story abruptly ends, since the Christian Socialist, which was serialising It, ceased publishing in December 1851.

Benjamin Wilson’s The Struggles of an Old Chartist is dry by comparison. Published In Halifax in 1887 it recounts many events of Chartism from the Peterloo massacre of 1319 to the general election of 1886.

Testaments of Radicalism includes a few Illustrations and is competently indexed.