By Alfred Jenkins

The intellectual condition of England at the time when Thomas Paine entered the world in 1737 and for many years afterwards is well described by Friedrich Engels: ‘The peasants at that time used to lead a quiet, peaceful life of honest piety harassed by few worries, but on the other hand inert, not united by common interests and lacking any education or any mental activity; they were still at a prehistoric stage of development. The situation in the towns was not very different. London alone was an important trade centre; Liverpool, Hull, Bristol, Manchester, Birmingham, Leeds and Glasgow were hardly worth mentioning. Spinning and weaving, the main branches of industry, were practised for the most part in the country, or, at least, outside the towns, on their outskirts. Metal-working and pottery-making were still at the handicraft stage and thus what real developments could be expected in the towns? The unequalled simplicity of the franchise spared the townspeople all political cares; they were nominal Whigs or Tories but knew full well that In fact it made little difference, since they did not have the right to vote. The town dwellers consisted exclusively of petty merchants, shopkeepers and artisans and theirs was the familiar life of the small provincial town, quite inconceivable in the England of today. Mines were still only being exploited on a small scale; iron, copper and tin deposits were left more or less untouched and coal used only for domestic purposes. In short, England was then in a position, in which unfortunately the majority of the French, and in particular, the Germans still find themselves, in a position of antediluvian apathy with regard to anything of general or spiritual interest, in social infancy, when there is as yet no society, no consciousness and no activity. This position is a de facto continuation of feudalism and medieval mental apathy, which will only be surmounted with the emergence of modern feudalism, the division of society into property owners and the propertyless. (“The Position of England in the Eighteenth Century.” Vorwarts & August 31, September 4,7 & 11, 1844.)

This benighted condition did not, however, prevent the English from regarding their country as the centre of the earth. Oliver Goldsmith, who came to London from Ireland in 1756, was greatly impressed by this attitude of mind. In his Citizen of the World, published in 1762, he wrote: ‘The English seem as silent as the Japanese, yet vainer than the inhabitants of Siam.’

“Pride seems the source not only of their national vices, but of their national virtues also. An Englishman is taught to love his king as his friend, but to acknowledge no other master than the laws, which himself has contributed to enact. He despises those nations who, that one may be free, are all content to be slaves; who first lift a tyrant into terror and then shrink under his power, as if delegated from Heaven. Liberty is echoed in all their assemblies; and thousands might be found ready to offer up their lives for the sound, though perhaps not one of the number understand its meaning. The lowest mechanic, however, looks upon it as his duty to be a watchful guardian of his country’s freedom, and often uses a language that might seem haughty, even in the mouth of a great emperor who traces his ancestry to the Moon.”

Goldsmith’s “Citizen of the World,” is an imaginary Chinese traveller who is represented as writing home to a friend: “This universal passion for politics is gratified by daily gazettes, as with us in China. But, as in ours the emperor endeavours to instruct his people, in theirs, the people endeavours to instruct the administration. You must not, however, imagine that they who compile these papers have any actual knowledge of the politics, or the government, of a state: they only collect their materials from the oracle of some coffee-house, which oracle has himself gathered them, the night before, from a beau at a gaming-table, who has pillaged his knowledge from a great man’s porter, who hashed his information from the great man’s gentleman, who has invented the whole story for his own amusement, the night preceding.”

In the article which we have quoted, Engels writes: *It was while the industrial revolution was taking place that the democratic party came into being. In 1769, J. Horne Tooke founded the Society of the Bill of Rights, in which, for the first time since the republic, democratic principles were discussed again. As in France, so these democrats were men of purely philosophical education but they soon found that the upper and middle classes were against them and that it was only the working-class which lent their principles an ear.” In actual fact, however, this did not take place immediately. Francis Place, who was in a very good position to know, wrote that: “At this time there was no political public, and the active friends of parliamentary reform consisted of noblemen, gentlemen, and a few tradesmen.

“Neither these societies nor the other political bodies at that period had any continuous existence; they met occasionally, talked over the concerns of the moment, ordered a tract to be printed or an advertisement to be buried in the newspapers. Their proceedings were neither adapted for, nor were they addressed to, the working people, who, at that time, would not have attended to them.” (‘Address of the Metropolitan Parliamentary Reform Association,” 1842. British Museum, Add.Mss.27810,ff.5-8.)

“The struggle with the North American colonies,” wrote Karl Marx, “awed the Hanoverian dynasty at that time from the outbreak of an English Revolution, systems of which were alike perceptible in the cry of Wilkes and the letters of Junius.” (“The Principal Actors in Trent Drsma.’ Die Presse. Dec. 8.,1861.) This may seem surprising in view of such statements as that of Lord Camden, who had resigned his office as Lord Chancellor on account of his opposition to the war: “I am grieved to hear that the landed Interest is almost altogether anti-American, though the common people hold the war in abhorrence and the merchants and tradesmen, for obvious reasons, are altogether against it.” (Chatham. Correspondence. V4. p.401.) This, however, is probably an over-estimate of the political understanding of “the common people.” Opposition from the merchants and manufacturers, especially those who had suffered from the prohibition or trade with North America, was certainly very strong. Edward Gibbon, then a Member of Parliament, wrote to his friend, J. Holroyd, afterwards Earl of Sheffield, on January 31st., 1775: “Hitherto we have been chiefly employed in rending papers and rejecting petitions. Petitions were brought from London, Bristol, Norwich, etc., framed by party and designed to delay. By the aid of some parliamentary quirks, they have all been referred to a separate inactive committee, which Burke calls a committee of oblivion, and are now considered as dead in law.” In December 1777, a report was sent to Lord Sandwich, then at the head of the Admiralty, from one Thomas Rawson of Nottingham. This town is without exception the most disloyal in the Kingdom, owing in great measure to the whole corporation ( the present mayor excepted ) being dissenters, and of so bitter a sort that they have done and continue to do all in their power to hinder the service by preventing as much as possible the enlistment of soldiers.” (Barnes, G.R. & Owen, J.H. Editors. The Sandwich Papers. Vol.1.p.340.)

In all these towns, however, the common people only signed the petitions against the American war when they were set in motion by those who were considered to be their social superiors. Nearly twenty years later, after a great deal had happened to widen their horizon, Charles James Fox in conversation with another politician: “made use of this (for him very) remarkable expression, that the husbandmen and labourers thought so little of public matters that he should as soon think of consulting sheep on the propriety or impropriety of Peace as the people who had care of them, or in general the lower order of peasantry. That in towns, from their ale-houses, clubs, etc., they turned their thoughts more to political subjects. (Browning, O. Editor. The Political Memoranda of Francis Fifth Duke of Leeds. Camden Society,) William Cobbett tells us that his father, a small farmer and inn-keeper in Surrey, read the newspapers and defended the Americans. When Cobbett senior expressed these sentiments at Weyhill Fair, however, the astonished company gaped open-mouthed in wonder that a man in their position in life should express any political opinions at all. When all the government had really become unpopular it was rescued by the Gordon Riots, directed against the Roman Catholics. When they were over Edward Gibbon wrote to his stepmother: “The measures of Government have been seasonable and vigorous, and even opposition has been forced to confess that the military power was applied and regulated with the utmost propriety. Our danger is at an end, but our disgrace will be lasting, and the month of June 1780 will ever be marked by a dark and diabolical fanaticism which I supposed to be extinct, but which actually subsists In Great Britain perhaps beyond any other country in Europe.

After the ending of the American war the majority of the British people sank back into their old somnolence. As Francis Place put it: Efforts to procure a reform in the House of Commons were made in many places. The number of public meetings and of petitions to the House of Commons increa- sed continually, when the coalition of Lord North and Charles James Fox, in the spring of 1783, caused an opinion to be generally entertained that no faith could be reposed in public men, and suspended all active proceedings in favour of parliamentary Reform; which lingered on, and were at length, nearly extinguished. The conclusion of the war was followed by a great economic revival and many people were never before or afterwards so prosperous as they were in the years from 1783 to 1793. This is reflected in the scenes of country life painted by George Morland, somewhat sentimental but drawn from real life.

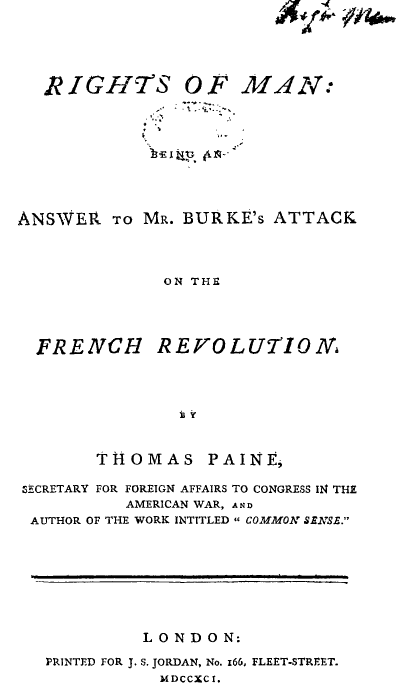

The first support for the French Revolution of 1789 came from the “middle classes,’ especially the Nonconformist manufacturers and the attitude of the working class varied from indifference to hostility. There was very little in the first part of Rights of Man to which a prosperous Nonconformist could object. Strutts, the Unitarian textile manufacturers of Belper in Derbyshire distributed copies among their workers who read them when the mill was stopped through lack of water power and threw them into the water. When in 1791 the leading citizens of Birmingham held a dinner to celebrate the anniversary of the fall of the Bastille there was a violent riot followed by similar demonstrations in other places directed in the first place against the Nonconformists. It was only the publication of the second part of The Rights of Man, with its fifth chapter showing what could be done if there was no National Debt, which for the first time showed the advanced section of the working class that political reform could really turn to their benefit. The ideas were not really original, the criticism of the National Debt having already been made by Dr. Richard Price, but the novelty was in their exposition. For the first time they were expressed in language which working men could understand, by one who had himself been a working man.