By Carl Shapira

IS IT REASONABLE to believe that the man wrote ‘all men are created equal” also owned several hundred slaves and considered blacks “inferior to whites in the endowment of mind and body?”

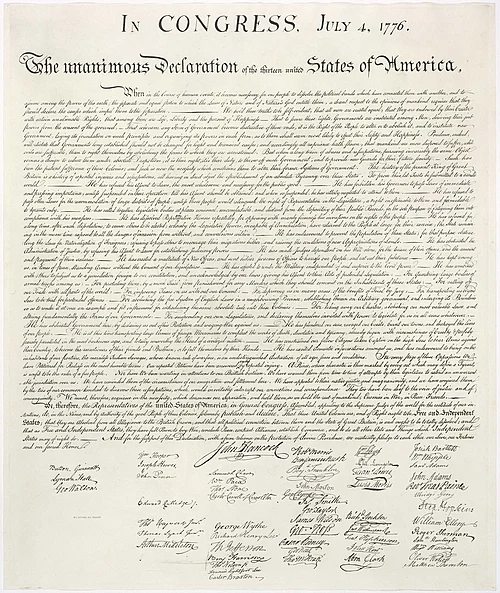

The first phrase, of course, is from the Declaration of Independence, the second is from the writings of Thomas Jefferson, presumed author of the Declaration.

That Jefferson owned slaves (so did Washington) does not diminish his stature as one of the great libertarian fathers of the republic. A powerful advocate of the separation of church and state, Jefferson framed the Statute of Virginia for Religious Freedom, an achievement guided by his argument that “our civil rights have no dependence on our religious opinions, more than our opinions in physics or geometry.” To Jefferson, “the care of every man’s soul belongs to himself.’ Refounded the University of Virginia, the first truly non-sectarian college in America. A gifted architect, he also designed the buildings.

Despite his social position as a wealthy plantation owner, Jefferson persistently held that “nothing is more certainly written in the book of fate that these people (slaves) are to be free. As a master, Jefferson was kind to a fault, and the evidence suggests he was loved by his slaves.

Yet even one of Jefferson’s most sympathetic biographers, Gilbert Chinard, was distressed by the Virginian’s racial attitude. Chinard wrote, *He was a Puritan in so far as he felt that the American people were a ‘chosen people,’ and Anglo-Saxon.” And Claude G. Bowers, in his book, “The Young Jefferson”, provided a practical reason for Jefferson’s ownership of slaves by contending that it “would have been Quixotic and destructive of his own economic life.’ Considering America’s largely agrarian economy at that time, Bowers was probably right. But with all things weighed, could Jefferson still have actually written a document proclaiming that all men were equal?

There is strong evidence to suggest he didn’t write the Declaration.

On June 10, 1776, Jefferson was made chairman of a committee chosen by the Continental Congress to draft the Declaration. Other members of the committee included John Adams, Roger Sherman, Benjamin Franklin and Robert Livingston. The five bickered over who should actually write the text, but the job was finally entrusted to Adams and Jefferson, the former for his fame as a lawyer, the latter for previously writing the preamble to the Virginia constitution. But neither Adams nor Jefferson considered himself capable of writing the document and both wished to shun the responsibility. Adams late recalled their dispute:

The Committee met, discussed the subject, and then appointed Mr. Jefferson and me to make the draught; I suppose because we were the two highest on the list. The sub-Committee met; Jefferson proposed to me to make the draught. I said I will not.

‘You should do it,’ said Jefferson.

‘Oh,no.’

‘Why will you not?’, asked Jefferson.

‘I will not.’

‘Why?’, insisted Jefferson.

‘Reasons enough’, replied Adams.

‘What can be your reasons?’

‘Reason first, you are a Virginian and Virginia ought to appear at the head of this business. Reason second, I am obnoxious, suspected and unpopular.'”

Jefferson finally agreed to compose the manifesto, a job that would have taxed the facilities of even the most seasoned statesman, such less the sensibilities of a 33-year old congressman.

Aware that the slavery question was singularly the most volatile issue, Jefferson knew that some of the representatives of slave-holding states would veto any proposal to free the blacks. Nevertheless, the document had to be fretted.

During this crucial period Jefferson was in close touch with Thomas Paine. Earlier that year, Paine had written Common Sense, the stirring pamphlet that pressed for separation from Britain. In his 47 page treatise, Paine had not only directed that a “declaration for Independence’ be drawn up, but had urged Americans to set a day aside “for proclaiming the Charter. Brilliantly conceived, the pamphlet was unmatched in its persuasive power.

An outspoken enemy of slaver, Paine was also the first to publicly advocate emancipation of the Negro in his Essay on African Slavery in America, published in Phladelphia in March 1775. This work became so popular in such a short time that only a month after its appearance, the first anti-slavery society was formed in Philadelphia.

Sharing similar ideals, Jefferson and Paine became intimate friends, an alliance that was culminate in 1791 with Jefferson’s endorsement of Paine’s herculean handbook of democracy, Rights of Man.

Three days after the committee was appointed, Jefferson submitted to Adams, then to Franklin, a rough draft of the Declaration. Corrections, says Bowers, were made ‘mostly in phrasing and in the choice of words.’ Finally, on June 28, the polished document was presented to Congress in Carpenter’s Hall, Philadelphia, for approval. As was expected, objections from the southern delegates, particularly those from Georgia and South Carolina, caused the delegation of the clause:

“He (George III) has waged cruel War against human Nature itself, violating its most Sacred Rights of Life and Liberty in the Persons of a distant People who never offended him, captivating and carrying Them into Slavery in another Hemisphere, or to incur miserable Death in their Transportation thither…He has prostituted his Negative (veto) for Suppressing every legislative Attempt to prohibit or to restrain an execrable Commerce, determined to keep open a Market where MEN Should be bought and Sold, end that this assemblage of Horrors might Want no Fact of distinguished Die.”

Adams did all he could to defend the clause which could have finally put an end to the slave trade. Jefferson, too, was disappointed and partially blamed “our northern brethren…for though their people had few slaves themselves, yet they had been pretty considerable carriers of them to others.

Jefferson removed the clause and sent the edited copy to his fellow delegate from Virginia, Richard Henry Lee, who had originally proposed to Congress that a declaration be drawn up. Lee replied:

“I thank you much for your favour and its enclosures by the post, and I sincerely wish, as well as for the honour of Congress, as for that of the States, that the Manuscript had not been mangled as it Is.”

Lee regretted that the Declaration had been “mangled” and Adams felt that “the purpose of the Declaration was to level all distinctions.”

The mangled Declaration was ratified on July 4.

Now despite his prudent opposition to slavery and the fact that the Declaration, as we know it, is in Jefferson’s handwriting, there has been doubt that he actually wrote the original draft containing the slavery clause. Morally, Jefferson hated slavery; economically, he depended upon it. In view of the circumstances, could Jefferson have beer so profoundly moved as to write a clause against slavery? And what of the whole stricture of the Declaration? Its literary style? Phraseology? Are they characteristic of Jefferson?

Historial, Julien P. Boyd was not convinced that Jefferson wrote, most importantly, the original draft of the Declaration. In his scholarly brochure, The Evolution of the Text, published by the Library of Congress in 1943, Boyd said “there is evidence in the Rough Draft itself, the significance of which apparently has been overlooked, pointing to the fact that the Rough Draft was copied by Jefferson from another and earlier document or documents.” Yet Boyd gave no indication as to what “document or documents” Jefferson could have copied from.

Boyd may not have been aware that a more positive view was set forth in 1892. Biographer Moncure D. Conway, in his two volume , Life of Paine described the events of June 1776: “At this time Paine saw much of Jefferson, and there can be little doubt that the anti-slavery clause struck out of the Declaration was written by Paine, or by someone who held Paine’s anti-slavery essay before him.

Dr. Conway felt that the literary style and sentiments of the deleted slavery clause ‘are nearly the same” as these phrases from Paine’s essay:

“That same desperate wretches should be willing to steal and enslave men by violence and murder for gain is rather lamentable than strange… these inoffensive people are brought into slavery, by steeling then, tempting Kings to sell subjects, which they can have no right to do, and hiring one tribe to war against another, In order to catch prisoners…Our traders In MEN, an unnatural commodity must know the wickedness of that SLAVE TRADE, if they attend to reasoning, or the dictates of their own hearts; and such as shun and stifle all these, willful sacrifice Conscience, and the character of integrity to that golden Idol… to go to nations… purely to catch inoffensive people, like wild beasts, for slaves, Is an height of outrage against Humanity and Justice.”

In support of Dr. Conway’s theory, Joseph Lewis, late author and Secretary of the Thomas Paine Foundation, maintained that the use of the word ‘hath” in the Declaration was vital evidence indicating the handiwork of Paine. Lewis argued that the “old English word was not generally used by the people of the American colonies, with the exception of the Quakers.’ Paine was of Quaker origin.

Lewis pointed out that while the word was used only once in the Declaration, it nevertheless “may be the key which unlocks the secret to many of Thomas Jefferson’s most important papers…. In his ordinary correspondence and his individual State documents, Jefferson does not use the word once, despite the fact that these voluminous writings aggregate more than three million words.”

Yet, Lewis argues, “In Common Sense alone, a pamphlet of only fifty thousand words, Thomas Paine used the word ‘hath’ at least one hundred and twenty times.

The word ‘hath” appears in this phrase frame the Declaration: ‘and accordingly all experience hath shewn…’ (Lewis also noted that the word shewn as spelled with an “e” in the Declaration, was Paine’s way of writing it. ‘The word is always spelled with an “o” in Jefferson’s writing, and was the prevalent way of spelling the word in the colonies at that time.’)

Prior to Common Sense, Paine also used the word ‘hath’ in one of his provocative calls for Independence. In this work, published in the Pennsylvania Magazine in October, 1775, Paine intimated that the inevitable document of separation should also abolish slavery once and for all:

”I firmly believe that the Almighty, in compassion to mankind, will curtail the power of Britain. Ever since the discovery of America she hath employed herself in the most horrific of all traffics, that of human flesh, without provocation, and in cold blood ravaged the hapless shores of Africa. When I reflect on these, I hesitate not for a moment to believe that the Almighty will separate America from Britain. Call it Independency or what you will if it is the cause of humanity it will go on.”

And later, in Common Sense, Paine coordinated the precents of the Declaration:

“Were a manifesto to be published, and dispatched to foreign courts, setting forth the miseries we have endured, and the peaceful methods which we have Ineffectually used for redress; declaring at the same time that not being able longer to live happily or safely under the cruel disposition, of the British court, we had been driven to the necessity of breaking off all connection with her…such a memorial would produce move good effects to this continent than if a ship were freighted with petitions to Britain.”

To say unequivocally that Thomas Paine wrote the original draft of the Declaration of Independence exceeds the limits of speculation. But one of the first questions a skeptic might ask would be why, if Paine wrote it, he never admitted authorship.

There are several plausible reasons.

First, he was not a member of the Continental Congress and therefore had no official authority.

Second, he was an Englishman. At the time of the Declaration, he had been in America only two years. Hence, he would have been open to suspicion. That is why Paine wrote Common Sense, published only five months before the Declaration, together with numerous prior works, he used pseudonyms.

Thirdly, he characteristically chose to remain silent on anything that could damage America’s reputation even to the sacrifice of his own literary pride. Loyalty to principle, rather than fame, was later expressed “But as I have ever been dumb on everything which might touch national honour so I mean ever to continue so.”

It is also relevant to mention that linked with Paine’s impassioned pleas for independence was his clear vision and support for an American republic:

“The mere independence of America, were it to have been modeled after the corrupt system of the English government would not have interested me with the unabated ardor it did. It was to bring forward and establish the representative system of government that was the leading principle with me in all my works during the progress of the revolution.”

On the other hand, Adams and Jefferson, in all their years of association and correspondence, widely differed in ideas on government and avoided discussion of America’s political destiny. In a letter to Jefferson, Adams recalled:

“You and I have never had a serious conversation together that I can recollect concerning the nature of government. The very transient hints that have passed between us have been jocular and superficial, without ever coming to any explanation.”

With the evidence already presented, it is not inconceivable that Paine, with remarkable perception and clearheaded purpose, wrote the original draft of the Declaration of Independence. In view of his irrepressible denunciation of slavery, vigorous literary style and similarity of his anti-slavery essay to the deflated clause, the theory of his authorship is plausible. The spelling and use of the words “hath” and “shewn,” peculiar to Paine throughout his writings, together with his close contact with Jefferson during the sultry months of 1776, further enhance that possibility.

But there is another piece of evidence, perhaps the most enigmatic of all, that adds more to the mystery. It is a puzzling sentence contained in one of Paine’s last letters to Congress. The letter was written in 1808, one year before he died. Paine was impoverished and was desperately trying to obtain a small allowance:

As to my political works, beginning with the pamphlet Common Sense, published in the beginning of January, 1776, which awakened America to a declaration of independence (as the president and vice-president both know), as they were works done from principle, I cannot dishonour that principle by asking any reward for them.”

It is difficult to determine what Paine is bringing to mind. It sounds sarcastic when he says, “as the president and vice-president know” (Thomas Jefferson was president and George Clinton was vice-president). What is it that they know? That he (Paine) wrote the Declaration of Independence? Or that his political works inspired the manifesto to be written? We know of his perpetual silence “on everything which might touch national honor. “Therefore, even In his most destitute state, Paine would never disclose secrets injurious to America’s reputation.

But as mysterious as the circumstances are, another firebrand of the Revolution, Samuel Adams, was more convinced: “There is as much evidence in favour of Thomas Paine’s authorship of the Declaration of Independence as there is of any other man.”

What do you think?