By G. Hindiarch

ONE OF THE few indications Thomas Paine gave of the way his thinking developed, is his remark to his friend Rickman that he seldom passed five minutes of his life without acquiring some knowledge. This observation shows Paine’s general attitude to learning, and explains how he overcame the limitations of his restricted schooling that terminated at the age of thirteen. And it follows from this declared attitude, that Paine must often have been preparing himself for his next step forward.

All men of ability, even those of genius, continue to develop throughout their active lives. The immortal Beethoven enjoyed in youth the benefits of tuition from the greatest musicians in Europe, yet he still posited through recognisable stages of development, and in his later years declined to compose in his earlier style; but lovers of Beethoven’s music do not, reject the earlier works. Paine similarly progressed, and modifications to his earlier thinking do not deprive those views of interest, rather do they make them of special interest as showing the path by which he came to his maturity.

Students of Paine have always regretted that he left little information about himself, and that he was singularly, reticent about his personal life even in conversation, with his closest friends; the consequence of this remarkable modesty is that we still lack an adequate biography of this most exceptional man; nor is it likely that one can yet be supplied from the pen of one single writer. It is probable that a fair assessment of Paine, and of his achievements, will necessitate the combined efforts of several contributors, each an expert in one of the fields in which Paine achieved prominence. However, we are now in a position to consider in greater detail than has previously been possible, some of the influences which bore upon him in his formative years. One of the strongest of these early. influences was Wesleyan Arminian Methodism, a movement which came into being and flourished in Paine’s lifetime, and which not only effected his profoundly in his spiritual life but also aided him considerably in his practical affairs. It was probably Methodism that facilitated Paine’s entry into a new community when he moved from town to town, and it was his sympathy with Methodists which prompted Paine into journalism, thus helping him to mould himself into an accomplished commentator, ready and able to blaze into prominence as a propagandist in the New World.

The fact that Paine became an experienced journalist during his years in Lewes has not previously been brought to general notice, and this is surprising, since his newspaper work there has remained on record, and he left clues in his American writings which point to the existence of his earliest offerings to the public. These early essays, which I term the Lewes Writings, number more than forty varied articles in the form of letters to the Sussex Weekly Advertisers or Lewes Journal. They include novel and provocative views; they display not only Paine’s mastery of the written word but also some forms of writing, such as satire, which he does not employ elsewhere, and they are revealing in considerable degree of the man behind the pen, of his methods, and of his objectives.

As might be expected of a commentator who was keenly aware of the influence of religion upon his contemporaries, Paine included in the Lewes Writings a number of observations on religious attitudes, and, after he announced his intention of making every seventh article a serious address, it was to religious topics that he turned for his most thoughtful dissertations. It is now suggested that it was Paine’s religious evolution that laid the basis for his later advanced thinking in the secular field. A critical factor in this evolution was probably the influence of the Dutch theologian, Jacobus Arminius (1560-1609), whose interpretation of the message of Jesus was exhilaratingly unorthodox when it was enunciated by his followers in the remonstrance of 1610. Although rejected in Holland, it was accepted and developed in England, notably by John Wesley. The essential feature of Arminianism was that all men, not just a select few (as envisaged by Calvin) could share in spiritual grace. This philosophy outraged many highly-placed people, of whom the Duchess of Buckingham could have been acting as spokeswoman when she commented that the doctrines of the Methodists were ‘strongly tinctured with impertinence and disrespect towards their Superiors, in perpetually endeavouring to level all ranks and to do away with all distinctions.’ (Quoted by E. P. Thompson in The Making of the English Working Class, p. 46.) Arminianism, in fact, envisaged a form of spiritual democracy, which Wesley embodied into his teaching. It takes little imagination to see that a thinker of Paine’s originality and humanity would pass easily from this spiritual equality to the social democracy which the historian Trevelys considered to originate in Paine’s writing.(Trevelyan, G. M. English Social History, p. 468.)

The Lewes Writings show that Paine was conscious of breaking new ground and provoking discussion among his readers. It was perhaps awareness of his inexperience as a social commentator that prompted him to write, when explaining his motives:

“We don’t perhaps know enough of our own hearts to know always what our design is, but the object I seem to have in my eye is TRUTH, Truth moral and natural. And we are indeed apt to be very partial to our own judgments, and therefore, possibly (aim as I) I may sometimes shoot very wide of the mark; however, when I do, let any man candidly show me my error, and I will show him in return that I can retract an opinion as well as advance it. But no controversy, let matters go as they will.” (Sussex Weekly Advertiser or Lewes Journal, December 14, 1772 — here in after Lewes Journal.)

Some of Paine’s early paragraphs make particularly interesting reading, since they now appear almost prescient. Paine might already have sensed the odium that was later to be heaped upon his name when he observed:

“If you have a mind to know the outlines of any man’s real character, take a view of the original, get acquainted with the man himself. There is no other way. Common fame is but a common liar.” (Ibid. March 1, 1773.)

Although Paine did not leave us enough information to enable us to follow his advice and get acquainted with him when seeking to delineate his own character, there was one period in his life when he was not allowed to exercise his customary reticence: when he applied to join the Excise, he was required to declare many facts about himself, and his personal records in the service would have been periodically updated. These records would eventually have been made available to George Chalmers when he was commissioned to write his defamatory life of Paine under the pen name Francis Oldys.

The authenticity of biographical details of Paine’s early life included in that work is rooted in access to particulars placed on record in the excise archives by Paine himself.

Some comment on Chalmers is necessary, since the hostile nature of his life of Paine has led to it being dismissed too lightly. As I have previously demonstrated in a paper on Paine’s first excise period, Chalmers is in some respects an important witness for the defence rather than for the prosecution, because he took great care that his reputation as a researcher should not become damaged through quoting from a document subsequently shown to be unreliable.

Chalmers was a clerk in government service, but the term “clerk” has many shades of meaning, and Chalmers was chief confidential clerk to the first President of what came to be known as the Board of Trade. This was an influential appointment which afforded access to the records and facilities of other government departments. However, having obtained confidential documents, Chalmers often retained them with his own manuscripts instead of returning them, with the result that they were sold after his death with his own voluminous papers, and some have since turned up in the libraries of American universities. (Cockcroft, Grace Amelia. The Public Life of George Chalmers, New York, 1939.) It may have been Chalmers’ cavalier attitude towards confidential government papers which led to the passing of the first Public Record Act after his death.

The importance of Chalmers, so far as Paine is concerned, is that clearly expressed statements of fact in Oldys’ biography need to be carefully considered and not set aside without very good reason. But this is not to say that we should be deceived by Chalmers’ clever introduction of surmises and reconstructions that are calculated to mislead; reading his words with a care equal to that he employed in writing them often reveals the deceptions.

The purpose of this paper is early traced from his first period in London. At that time he supported himself by practising his original trade, stay-making, in the workshop of the old London staymaker John Morris. Morris is known to have indicted on a long from 6 to 8 o’clock per and to have opposed the attempt by workers in the trade to secure a shortening by one hour in the evening. (Barry, Alyce. “Thomas Paine, Privateersman.” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, 1977.) The arduous day worked by Paine and his fellows is but one indication of the harsh conditions then endured by the working population of London. Many people lived in conditions of squalor, insecurity, disease, physical danger from collapsing buildings, and with little prospect of advancement as we nowadays understand the term.

It was consistent with the general harshness of that day, and with the policy of encouraging acceptance of the consequences deemed to punish even minor criminal activity, that the gallows was made the scene of executions as public entertainments. Paine has left us a record of his own reaction to these grisly events:

“Can anything give in so striking a light the callous insensibilities of an unfeeling heart, as the number of happy faces to be seen on these melancholy occasions? Streets through which the poor outcasts of society are to pass lined with crowds of people, and most of them as merry as if they were going to the exhibition of some uncommon show; and (to make the scene quite complete) you see bakers coming along with their aprons full of buns for the spectators to regale themselves with. O sensibility, whither art thou fled? Dost thou reside with the Cherokees, or hast thou taken shelter in some of the deserts of Africa?” (Lewes Journal, May 17, 1773.)

Few philanthropists or religious leaders set themselves to bring positive mitigation of the conditions of the working people by direct approach to them, but historians of the period have singled out one notable exception to this general observation.

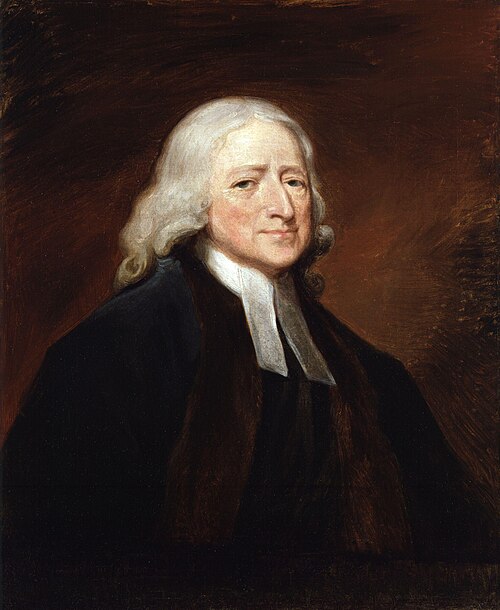

The Methodists did concern themselves to reach out and proffer spiritual comfort to the underprivileged; they also brought those who responded into organized groups, in which the spiritual and moral welfare of each was accepted to be the concern of all his fellows. The originator of the Methodists was John Wesley, an indefatigable worker in his cause who was remarkable not only for the many thousands of outdoor meetings he addressed all over the country, but also for his great talent for organization, which led to the setting up of a nation-wide network of communicating local societies.

It is important to bear in mind that Wesley opposed separation of the Methodists from the Established Church; he and his followers remained members throughout his life. There was thus no bar to a Church of England member playing an active part in Methodist affairs, even though he was bound to be a declared Anglican.

It is probable that the young Paine joined the Methodists during his first period in London, and that he was impelled to do so by a desire to participate in their endeavours to bring spiritual readings to working people, a worthy cause to which his religious tenets and social conscience alike would have compelled him.

The Bishop of London at that time was Thomas Sherlock, whom Paine has introduced for mention in the Lewes Writings as a very worthy and ingenious gentleman. The National Biographical Dictionary records that Sherlock cultivated kindly relations with those who dissented from orthodoxy, and his example may have facilitated Paine’s membership of Wesley’s movement. (Ibid. March 15, 1773.)

It is easy to scoff at another man’s personal religious beliefs, and Methodists have been the butt of much criticism by those who do not agree with them. Some commentators have found difficulty in comprehending how the movement could have exerted such a strong appeal to the industrialised workers, and evoked from them an enthusiastic response; yet that it did so is an undeniable historical fact.

The explanation may well be that Methodism, like other great popular movements, must be viewed against the social conditions in which it arose, and not judged by those of later days, after many changes had taken place, including some which had been inspired by the movement itself.

Dr. E. P. Thompson, in *The Making of the English Working Class*, has drawn attention to the transmission of some aspects of Methodist organization to working-class societies, and he mentions, too, the Methodist “ticket” which was to be widely copied by radical associations. He points out that this ticket of church membership could serve as a ticket of entry into a new community when a worker migrated from one town to another. (Thompson, E. P., op. cit., pp. 47 and 417.)

Paine possibly made use of a Methodist ticket when he left London in 1758, and entered into new employment in Dover with another stay-maker, Mr. Grace, for Grace was a prominent Methodist in the town, and Paine may have learned of the vacancy on his staff through church contacts.

It was during Paine’s association with Grace that he made his first authenticated appearance as a Methodist preacher. Grace was a class leader, and Paine went with him to class meetings, one of which a preacher failed to keep his engagement, and Paine was invited to conduct the service in his stead.

The invitation would probably have been issued by Grace as the class leader, who would have had opportunities to form well-based opinions on Paine’s outlook and moral qualities; he would also have known whether Paine had sufficient experience of the Methodist cause to be fitted to play this leading part in Grace’s own society.

This incident at Dover was brought to light in the Methodist Recorder of August 16, 1906, and it was subsequently recounted in the standard edition of John Wesley’s Journal, in a footnote by its editor, Nehemiah Curnock, on page 31 of volume 8. Curnock was a previous editor of the Recorder, and he would not have repeated the report unless he was sure it was an authentic record.

Paine preached in a meeting-house in Limekiln Street, which by 1906 had been vacated for larger premises. Wesley preached in the same meeting-house on September 19th, 1759, when Paine was still in the vicinity of Dover, and it would be very surprising indeed if Paine was not a member of the congregation on that occasion.

According to Oldys, Paine remained with Grace almost a year before moving to the nearby town of Sandwich to set up business for himself, with the assistance of £10 advanced by Grace. Another Methodist practice must now be mentioned: that of assisting fellow members of a group financially.

The contemporary publisher James Lackington, in his memoirs, acknowledged that he owed his own start in business to a Methodist advance, and Paine’s £10 was probably another instance of this benevolent Methodist practice. But it is likely that Paine was supported in his move to Sandwich not merely so that he could start his own business but also to found another Methodist group; for Oldys speaks of a tradition that Paine preached in his lodgings there, and this strongly argues that Paine was the leading light in a new class gathering around him.

The Methodist Recorder suggests that Grace may have been the first class leader in Dover, and if so he would have been gratified to see his protégé following in his footsteps.

With a new business to attend to, and a new Methodist class to build and guide, Paine would have been a very busy young man in Sandwich, with little time for any further demanding interests. Yet it seems that it was only five months after his arrival there that he married Mary Lambert, after what must have been a short courtship; it is quite possible that Mary came to know and admire Paine through membership of his congregation.

Oldys has suggested that Grace’s daughter, who would have heard Paine preach in Dover, was also romantically attracted to Paine, and congregational romances involving young preachers are by no means rare. Paine’s first marriage, as we know, was short-lived, and the circumstances of its ending have never been positively ascertained.

Years after, in an essay on unhappy marriages, Paine referred to the risks of marrying in haste; if personal experience underlay his comments, it is more likely to have been associated with his first courtship than his second, for his marriage to Elizabeth Ollive did not take place until he had known her for three years, and had been her partner in business for half that time. (Foner, Philip S. The Complete Writings of Thomas Paine. Vol. 2, p. 1118; here in after Writings.)

After the termination of his first marriage, Paine changed his way of life and became an Excise Officer. His first excise period has been researched and written up in a separate paper, copies of which have been lodged with the Thomas Paine Society and the American Philosophical Society to ensure that the new information therein, and the reasons for my conclusion that Paine was unjustly dismissed from Alford, may remain permanently on record.

No indications have been found that Paine continued to preach during that period, but the point has scarcely been covered, since the Lincolnshire Methodist History Society possesses no records for Alford in the 18th century, and it is there that Paine is most likely to have continued the practice.

On his subsequent return to London, Paine probably resumed contact with his original Methodist group, and through it may have secured his post at the academy of Mr. Noble in Leman Street, for Noble was an ordained minister who also held Arminian views, and hence would have been well disposed towards Wesleyans. (Payne, E. A. Letter to The Times Literary Supplement, 31 May 1947, p. 267.)

Paine was restored to the Excise within a year, but the position he was offered, at Grampound in Cornwall, was similar to the one he had held at Alford, and fraught with similar risks; that Paine was wise in asking to await another vacancy was demonstrated by subsequent events.

In declining the Grampound post, Paine risked being denied a further excise appointment, but this may not have seemed very important to him, for he was by then strongly drawn towards a career as a Methodist preacher. That he took this project seriously is shown by Oldys’ revelation that he sought from Noble a recommendation for ordination, but that Noble was unable to comply because Paine lacked classical education.

Oldys’ reason for this disclosure can only have been to bolster the reputation of his biography, for when it appeared there would have been many who knew of Paine’s preaching activities and who would have noticed the omission had Oldys ignored them.

Paine’s failure to secure ordination did not lead to his giving up preaching, for, like other Methodist lay preachers described by Lackington, he preached in Moorfields and other places.

Moorfields was at that time an open site favoured by Londoners as a gathering place in their limited hours of leisure. Notable sermons were preached there in the Methodist cause, both by John Wesley himself and by his original friend—later his doctrinal opponent—George Whitefield, who did not accept Arminianism, but preached instead a Calvinistic form of Methodism.

Lay preachers who were accepted and approved by the central Methodist organisation were sent out into the country in the summer months to preach on arranged circuits. This entailed considerable physical exertion and called for some aptitude for wayfaring on horseback.

Paine’s experience of riding the remote Lincolnshire countryside as an exciseman would have made him an obvious choice for itinerant preaching in that locality, and we know from Paine’s own essay *Forgetfulness* that he was indeed back in Lincolnshire in the summer of 1766 when he lodged at the house of a widow living in the fens. (Foner, P. S., Writings, Vol. 2, p. 1120.)

Lackington wrote of the practice of lay preachers lodging with members of the congregations they addressed, and he singled out widows for special mention. He moved away from Methodism in middle life (but returned to the fold towards his end) and his comments are somewhat malicious, but they contribute to our knowledge of the activities Paine was engaged in about this time.

Wesley’s original policy had been to accept only ordained ministers as his preachers, but the number available to him was too small to meet the demand, and lay preachers were increasingly used to address the many communities that assembled to hear the Methodist message—sometimes in sympathy, and sometimes in bitter hostility.

Lay preachers were encouraged to seek ordination, and this may have led to Paine’s own candidature. The employment of lay preachers is another example of democratic practices within the Methodist movement, and it was one of Wesley’s constant cares to restrict democratic tendencies to the spiritual plane and to discourage their incidence in the secular field under the banner of Methodism.

This was a practical policy forced upon him, for in the political climate of his day such a development could not have failed to provoke a strong reaction against his movement; its existence would have been threatened, and the source from which democracy drew its inspiration in both religious and secular fields could have dried up.

The reality of this threat was demonstrated in 1811, when Lord Sidmouth, as Home Secretary, introduced a Bill to restrict lay preaching, which was seen as subversive to the state, since “cobblers, tailors, pig-drovers, and chimney-sweepers” were claiming the right to preach.

Baptists, Congregationalists, and Unitarians joined with the Methodists to combat the Bill; five hundred petitions against it were laid before the House of Lords, and Lord Erskine (who had defended Paine) drew attention to the abstinence of Wesley and his followers from political affairs. The Bill was then withdrawn. (Semmel, Bernard. The Methodist Revolution. Heinemann, London, 1974.)

Although Wesley’s policy of keeping the democratic aspects of mainstream Methodism within the spiritual field may thus appear to have been justified by events, some of his preachers were not prepared to follow his lead on this point, and considered social philosophy to fall within their ambit.

Notable among these was Alexander Kilham, who became known as the champion of liberty and equality within the movement; this reputation earned him the accusation of being a “Tom Painite” and led to his being tried by the central Methodist authority on the ground that his activities would jeopardise the movement’s survival. (Ibid. pp. 118–19 and 121–24.)

When the persecution of Paine’s supporters is considered, the persistence of anti-Paine propaganda remembered, these fears become understandable, if not justifiable.

Some consideration of the secular effects of Methodist thinking has been thought necessary to show that membership of the movement was not inconsistent with the development of Thomas Paine into one of the foremost thinkers of his age, but this paper is not the place for a detailed examination.

Readers who might like to look more deeply into the revolutionary aspects of Methodism may find interesting a perusal of Bernard Semmel’s book *The Methodist Revolution*, in which he postulates the thought-provoking thesis that it may have been because the English working class had already achieved spiritual democracy through Methodism that the people were not impelled to pursue social democracy through revolution, as were the American and French peoples during the 18th century.

When Paine was given the opportunity to return to the Excise in March 1768, his decision to accept the posting to Lewes may have been a difficult one, as it entailed cessation of itinerant preaching; but it did not entail termination of other activities within the movement, and Paine may have seen a settled period at Lewes as offering opportunities for further study.

He had probably kept in touch with the service through the London officers; indeed, it is difficult to see how he could have formed his association with Thomas Sykes (the first signatory to his subsequent salary petition) at any other period. (T.P.S. Bulletin, No. 1, Vol. 6, 1977, p. 14.)

Sykes’s office was in the City of London, and Paine may have approached him for information about the Grampound post when it was offered him; once Paine had become personally known to the London excisemen, they would have observed his preaching activities at Moorfields and might thus have discerned his potential as a leader.

Dr. Johnson observed and commented upon the singular ability of Methodist preachers to express themselves “in a plain and familiar manner, which is the only way to do good to the common people.” (Semmel, B., op. cit., p. 20.) The excisemen at Paine’s meetings might have come to a similar conclusion.

Although Paine’s period at Lewes was perhaps the most important one in his early life, it has not yet been adequately portrayed. It is accordingly now proposed to summarise it and make known further information which has recently come to light.

As Paine went to Lewes as an Excise Officer, his first concern on arrival would have been to report at the excise office in the town, and he would thus have become immediately familiar with the White Hart Inn, where the Lewes excisemen had been quartered for decades.

The master of the inn, Thomas Scrace, was the officially appointed excise office-keeper, as the preceding masters had also been, and he was responsible for a number of minor excise functions which would have kept him on familiar terms with each of the nine Excise Officers based at his premises.

Scrace was a prominent member of the urban community, who took an active interest in public affairs as well as being in constant contact with the various “clubs” regularly held at his inn; he was probably the first person whose acquaintance Paine made in Lewes, and Paine could have had no more versatile an informant on the community he was joining.

Paine’s second concern would have been to ascertain where he could meet local people holding similar religious views to himself, and at that time they were associated with the congregation at the Westgate Chapel.

This was multi-denominational. It had been founded by a Lewes minister who had suffered displacement under the Act of Uniformity, and when conditions later eased sufficiently for him to obtain a fresh licence to hold meetings, the deeds of the new meeting house were designed to avoid repeating what was seen as the injustice perpetrated by that Act.

No particular mode of worship was prescribed, and ministers were free to dissent from the opinions of their predecessors. Paine may well have been pointing out the benefits of this broad approach to Christian worship, and deploring its absence elsewhere, when he wrote:

“How capable the best things are of being perverted to the worst purposes has been too clearly evinced by the many unhappy feuds and dissensions that have torn and distracted the Christian world. Such a variety of sects and parties have started up that it requires a very tolerable share of understanding to distinguish their very names: Arians, Socinians, Arminians, Lutherans, Calvinists, etc..

“Now whatever may have been the causes of such a diversity of tenets, the consequences we are but too well acquainted with. Our zeal has eaten up our charity. In quest of the shadow we have lost the substance, and the most essential duties of Christianity have been either mistaken or forgotten, while we have been disputing about circumstantials.

“If we could learn to be cool and dispassionate, we should then learn to be candid and open to conviction, and our differences would terminate happily, viz. in the detection of our own errors or those of our antagonists. But here we fail. Being warm and strenuous in the defence of our own sentiments, we don’t love to give our opposers a hearing.

“Hence it happens that many of our misunderstandings are literally nothing more than our not understanding each other.” (Lewes Journal, 1773.) (Ibid. September 6, 1769.)

Paine needed a permanent lodging, and when seeking one he would probably have consulted Scrace, for it is long-standing unofficial practice in local excise offices to maintain a list of available lodgings for the benefit of new-comers; there would have been a particular need for such a list at Lewes, for in the autumn of most years thirty-odd extra officers were drafted there to collect the duty on the hop harvest. The list would have been in the hands of Scrace, who was always present to greet new arrivals, and when he had ascertained Paine’s particular interests, Scrace probably recommended Paine to lodge with Samuel Ollive, son of a previous Westgate minister, whose residence adjoined the chapel. Ollive seems to have taken quickly to Paine, and would have been his sponsor with the Westgate congregation, which had always been notable for its strong tradition of public service. Ollive was serving his second term of high local office, and it is very likely that Paine’s association with him paved the way for his early election to the “Jury” of twelve prominent citizens who managed urban affairs; but Paine’s personal bearing and his reputation as a former preacher would doubtless have been the deciding factors.

At the time of Paine’s arrival, Ollive’s daughter Elizabeth was an assistant teacher at the school of a Mrs. Bridges, but this lady found it necessary to retire through ill-health shortly afterwards. Elizabeth seized the opportunity to open a school of her own, a bold step for a young girl, which she is unlikely to have been able to finance from her own resources; perhaps she needed the backing of her father, but if so his assistance was not long forthcoming for Ollive died in poor circumstances a few months later. Following a meeting of his creditors at the White Hart, his whole possessions, professional, domestic and personal, were sold under the hammer. The sale was advertised in two editions of the Lewes Journal, and on the second occasion another advertisement accompanied it:

THOMAS PAIN, and ELIZ. OLLIVE, Daughter of the late Mr. Sam. OLLIVE, near the West-Gate, Lewes, continue selling in the same Shop, all sorts of TOBACCO, SNUFF, CHEESE, BUTTER, and Home-made BACON, with every Article of GROCERY, (TEA excepted) Wholesale and Retail, at the lowest Prices. An entire new STOCK will be laid in as soon as the present Stock, now advertised for public Sale, can be disposed of. (Ibid. December 13, 1773.)

Suggestions that Paine re-opened Ollive’s business subsequently are now seen to be incorrect, since the advertisement makes clear that there was no break in trading; the business would presumably have passed into Paine’s sole ownership under the laws of the time when he married Elizabeth, but we already know that when they subsequently separated there was a division of the property. The public advertising of his partner- ship with Elizabeth is positive proof that his involvement was known to his excise superiors, who were based only a few yards from the Westgate premises, and it is prob- able that it was to avoid any possible objections from them that tea was excluded from the range of groceries for sale, for tea was the staple commodity of the contraband trade. The reason why Paine stopped lodging at Bull House on Ollive’s death is also now clear, since every stick of furniture and every shred of household linen was auctioned to pay Ollive’s debts, no living facilities would have remained there for him incorrect, since the advertisement makes clear that there was no break in trading; the business would presumably have passed into Paine’s sole ownership under the laws of the time when he married Elizabeth, but we already know that when they subsequently separated there was a division of the property. The public advertising of his partner- ship with Elizabeth is positive proof that his involvement was known to his excise superiors, who were based only a few yards from the Westgate premises, and it is probable that it was to avoid any possible objections from them that tea was excluded from the range of groceries for sale, for tea was the staple commodity of the contraband trade. The reason why Paine stopped lodging at Bull House on Ollive’s death is also now clear, since every stick of furniture and every shred of household linen was auctioned to pay Ollive’s debts, no living facilities would have remained there for him.

Nothing is positively known of the scholastic attainments of Elizabeth, but the general impression has been that she was a well-educated girl. The Lewes Writings, which were penned after Paine’s second marriage, contain a number of references not only to Milton and other English poets, but also to Latin poets, although Paine has generally been thought unversed in that language; Elizabeth may have had a knowledge of Latin, and she may have passed it to her husband, who had been at a disadvantage without a classical education when applying for ordination. It is quite compatible with Paine’s character, as we can now see it, with the religious vein that runs through the Lewes Writings, and with the general tenor of his observations on other ethical questions, that Paine could still have aimed at ordination during his Lewes period. As Elizabeth was the granddaughter of a former Westgate minister, it is conceivable that they both bore in mind the possibility of Paine becoming the minister of the liberal-minded Westgate congregation.

Paine’s appointment to Lewes was to Lewes 4 Outride, which means that he was one of the six riding officers who covered the countryside around Lewes on horseback. Each of them would have been responsible for a specified area, but the one Paine covered has not been identified; such circumstantial evidence as is available suggests that he may have been concerned with the vicinity of Uckfield. Excise work within the town limits was primarily laid to two town officers, but the central situation of the common office in the White Hart meant that Paine would have had some business in the town. The incidence of sickness and similar disruptions of normal arrangements might also lead to Paine making visits within the town, but mainly he would have worked in the country. After he lost his original lodgings on Ollive’s death, it is possible that he found a new residence in the country more convenient for his working practice than living in the town.

The countryside around Lewes was probably the most attractive area to which Paine was directed by the Excise Commissioners; Lewes stands at the edge of the ancient forest lands that once extended from the South Downs to the North Downs, and it was timber from those forests which fuelled the Sussex iron industry that was active when Paine was resident there. He recorded the impressions the countryside made upon him, and the thoughts it stimulated:

One of these Halcyon days, some time since, tempted me to extend my walk beyond its usual limits. I was drawn insensibly on, till I had gained a considerable eminence, where I was presented with a very striking prosp- ect. It was bounded on one side by a distant view of the downs, on the other by the Forest; the intervening tract of land was agreeably diversified with several pleasing objects, and the whole terminated by a beautiful sky. As the sun shone, and the air was remarkably still, I stood some time gratifying my eye with the landscape. “Ah! (thought I) if the human mind were always as serene and calm as the scene I have now before me, how pleasantly might we glide down the stream of life: But as it is in the greater, so it is in the little world, called man: our sunshine is still succeeded by storms: some rustling passion is still breaking in upon our repose, and depriving us even of those ration- al enjoyments we might otherwise innocently partake of.” (Ibid. September 7, 1772.)

Again Paine’s words appear prescient to modern readers. They appeared in December 1773; within months the Sussex countryside was swept from his daily life by his second excise dismissal, which came like a bolt from the beautiful sky he had admired.

Particular interest naturally attaches to the first of the articles in the form of letters that Paine addressed to the printer of the Sussex Weekly Advertiser, which in this paper is generally referred to by its alternative title of the Lewes Journal. It will now come as no surprise that Paine’s prime motivation was his sympathy with the endeavours of the Methodists, and that his object in writing it was to open the way towards a more rational appraisal of these endeavours than had recently been accorded them in the vicinity. Methodism exerted its greatest appeal in industrial districts, and it was still a contentious movement in conservative areas such as rural Sussex. The Lewes Journal in September 1772 carried a report of a Methodist preacher being harried from parish to parish by persecutors assailing him with missiles and rotten eggs. Paine showed in his first letter to the Journal that he was already the Man of Reason, opposed to mindless hostility, but seeking to counter it, not by confrontation, but by stimulating mild and thought-provoking suggestion:

Mr. Printer,

I BELIEVE, with no other instruments than plain truth and a little common sense I could dissect that paragraph in your paper which mentions the defeat of the Methodist troop in (or near) Uckfield. However, I shall only observe, that confronted and confused as they were with the all- powerful rhetoric of rotten eggs, broombats, their enemies must, at least, allow that it was only a common idea of generalship to quit the field, and make a prudent retreat. In the whole circle of Logic not a syllogism can be found that hath half the force of a missile weapon, directed at the outside of the head. People talk of convincing one another by force of argument; but ’tis all a joke, I assure you, compared to the dint of a broombat. In short, the oratory of the mob is in itself perfectly irresistible… But, by the bye, if we should ever live to see a thorough reformation take place, both in principles and practice, I am inclined to think it will never be brought about by mere dint of rioting and rotten eggs. I am told, a sensible magistrate upon the spot thought this but an awkward kind of reasoning, and therefore rationally enough desired the Logicians to desist from this species of argument. But you will say, “Are not these people in the wrong? And do not many of the Clergy oppose them?” They do, and I heartily reverence them for so doing, because I believe they do it from principle; they do it, because they suppose these people Schismatics. But we don’t know of the Clergy to go in print at the head of a mob to oppose them. No! Men of principle can’t do this. But let me whisper a word in your ear: If their discourses are really so stupid and unconnected as they are said to be, it would not be much amiss to let them convict and confute themselves; a much more rational triumph this, than one obtained by any other means whatever. (Ibid. November 2, 1772.)

Paine did not sign this letter with his name; in accordance with the custom of the time he cloaked his identity under a pen-name — one which leapt to my eye when I observed it on perusing a file of the Lewes Journal. Paine signed himself — A FORESTER.

My view that A FORESTER and Paine were the same person is based on the internal evidence in the Lewes Writings — of style and subject matter; on the logic of the pen- name, which Paine is known to have revived (without a slight variation) in America where he had no known connection with a forest; and on comparison of time factors including Paine’s known visit to London in the winter of 1772/3 to pursue his Case of the Officers of Excise. Paine’s actual departure for London appears to have been precipitate, for although he had arranged to supply a weekly feature to William Lee, printer of the Lewes Journal, he left Lewes without making arrangements for two-way correspondence, as is shown by his inserting a note in the town column of the paper for November 30th, 1772, which he knew Paine would read in the London coffee houses where the Journal was regularly circulated: “A line from Forester, acquainting the Printer where he may be wrote to, will be esteemed a favour. “

Lee was also the printer of the 4,000 copies of Paine’s Case of the Officers of Excise, which Paine was distributing about that time to his fellow officers, the Members of Parliament, and to prominent public figures, and it may be that Lee was seeking instructions for distributing some of the considerable bulk of pamphlets, which Paine may have wished to be done promptly in support of his personal efforts.

It is not practicable to include in this paper more than a selection from the Lewes Writings; those that now follow have been chosen as illustrations of my reasons for attributing their authorship to Paine, and also as examples of his thinking during his Lewes period: on religion, on society, and on his fellow men. With the welcome revival of interest in Paine, which seems to have been particularly strong in America following the bi-centennial celebrations, the time appears ripe for a new edition of his works, and if this is forthcoming, it is hoped that the Lewes Writings will become generally available in their entirety.

The following quotation foreshadows in some degree the first part of The Age of Reason. It is attractive writing, and is concluded by an incisive assessment of the fallibility of learning unsupported by understanding — which could only have been expressed by a mind as brilliant as that of Thomas Paine:

Among the various kinds of idolatry we have upon record, that of worshipping the heavenly bodies, seems of all others the most plausible and rational. Consider the Sun as an immense mountain of light and heat, ripening by his influence into life and action all the several tribes of the animal, mineral, and vegetable kingdoms, and you may, I think, easily conceive how obvious and natural it was for an uninstructed heathen to mistake such a body for the God of this lower world. I remember at school being much pleased with Herodotus’s worshippers of the Moon, waiting to hail and welcome their rising Goddess with all the festivities of music, and dancing. They were really idolaters of taste. In all the grand machinery of the creation, I hardly know so fine an object as a rising full Moon, especially in summer. After an oppressively hot day, which has thrown a languor upon both mind and body, can anything equal “The coming on of grateful evening mild,” ushered in by such a glorious harbinger? What exquisite painting! What scenery! A very luxury in nature. One of her richest repasts! Every sense seems regaled; every faculty harmonised and disposed to favour thought and reflection. And yet how lost, how utterly lost is all this to millions and millions! Why? — Because we all look through different glasses; one has the lens of his (mind’s) eye so thick and horny that he sees no objects distinctly. Some view everything through the dirty medium of gain; others through the misty glass of sensual pleasure. Some are blinded by ambition, others drunk and besotted by intemperance. But of all, none is more vexed by those who are TOO SHARP-SIGHTED TO SEE, or, in other words, who have too much learning to have any taste at all; who are so bewildered in the labyrinth of “falsely so called,” that they are lost to everything worthy of their notice. Admirable work this, to be learnedly stupid. A man in such a case is like a warrior pressed to death with the weight of his own armour. (Ibid. May 3, 1774.)

The next extract, which is also in religious vein, depicts Paine in the unfamiliar role of an apologist for revealed religion. It displays his remarkable ability to postulate an apparently strong proposition, and then to demonstrate its weakness in a few lines of concise, forceful and lucid reasoning, punching the message home by a strikingly effective homely illustration that exerts an immediate impact upon readers of all persuasions. But I think it is important to note that even when defending orthodox religion, Paine based his case not on quotations from the Bible, but upon the force of rational reasoning:

One of the solidest infidel batteries that have been played off against revealed religion is that it abounds in mysteries. “It is absurd” (say they) “to require your faith in matters confessedly above the reach of our understanding.” The objection at first sight appears formidable enough, but will vanish upon examination. It carries with it little or no force at all. Whether a thing exists and how it exists, are certainly two very distinct enquiries. Even among the objects of sense, which we may be supposed to be best acquainted with, we are every moment forced to acknowledge numberless truths, which, with the utmost stretch of our faculties, we can no ways fully conceive, nay, which we have hardly any competent idea of at all. The various modifications of matter, the exquisite mechanism and organisation of animal and vegetable bodies, &c., are (as to their first rationale) utter secrets to us, and so they will ever remain. A single blade of grass is as effectual a puzzle — with all the philosophers upon earth — as is the solar system, and twenty other systems added to it. (Ibid. November 14, 1772.)

The suggestion that Paine evinced no interest in social affairs of his day, before his emigration to America, is shown by the Lewes Writings to be quite unfounded. Paine’s consuming interest in his fellow-mortals is clearly expressed — almost off-handedly, as if such an obvious truism did not warrant taking up newspaper space to record — in a short parenthesis:

“…and (as I love to see human nature in all its shapes)…” (Ibid. February 20, 1773.) (These words might well be preserved as the standing reason why excisemen continue in their harassing and unremunerative profession, ground as they are between insensitive authority and the perplexed and resenting public.)

In another extract, Paine makes observations on humanity in much greater detail, and demonstrates that notwithstanding the apparent wide differences between the great and the lowly, there is much less real difference between them than many suppose:

I have sometimes thought that a work in which all the various movements of pride should be fully discussed, would consist at least of twenty volumes in folio; and I believe then, after the publication of the twentieth volume, the writer would find fresh matter starting up in his way. High life and low life are both equally full of it. Has a nobleman his attitudes, his peculiar manner, gait, &c.? So has a carter; I have seen it clearly in the carriage and conduct of his whip, and in his tone and manner of address to his horses… People may be poor, but they won’t let lords and ladies have all the pride to themselves. The villager has a world of his own (of which his cottage is the centre), and there he strives to cut a figure, as your great folks do in a higher sphere. The barber (forgetting himself) rises into a politician, trims the balance of Europe, and talks of Kings and Princes with all the freedom of a prime minister. (Ibid. October 20, 1772.)

Paine’s range of sympathetic interests extended beyond human affairs into the animal kingdom, and beyond that again into the domain of insects:

…Life is life, though it be in miniature, and it’s nothing but ignorance and prejudice that makes you think a creature beneath your notice, only because it’s less than yourself. To crush with your foot an inoffensive reptile, or otherwise needlessly maltreat any of the creatures that are put in your power, is the triumph of a little mind, and a species of cruelty which it will more than puzzle all your philosophy to justify. (Ibid. October 1772.)

But in reflecting upon creatures other than man, Paine was quite capable of pointing to the moral that man was by no means the vastly superior being he was popularly represented to be. The following reflection on the community life within an ant hill is an example of this, and it carries a sting that could have found some uneasy victims:

There’s not a state in Europe, I move, half the harmony that subsists in this little republic. Every individual Ant there is a patriot, I warrant him, and has the good of the community warmly at heart. Every individual Ant supports the character assigned him with equal dignity and propriety. And if such little beasts are susceptible of many passions, I dare affirm, they are well governed, all under due regulation and restraint, and all subservient to the public cause. Can you conceive of an Ant statesman selling his country and betraying the interests of the hillock to the enemy? I can’t. Can you form an idea of an Ant, whether peer, commoner, or what not, idly basking in the sun, and living at the expense of the public, without bringing in a single grain to the stock? There is no such to be found… And if I were to give you a list of human follies and extravagances, and then ask you if you thought each any place in this hillock, I think you must necessarily answer me in the negative. (Ibid. October 25, 1773.)

One aspect of Paine’s character which is well known, but for which he has been given too little credit, is his lack of personal greed, and his willingness — indeed his anxiety — to forgo pecuniary gain from the major works he envisaged as altruistic contributions to human philosophy. There have been many writers whose efforts have led to amelioration of want, or even to improvement in human conditions, and there have been many men and women of wealth who have generously contributed to charity. But if there have been philanthropists — other than Thomas Paine — who have donated the rewards from their literary successes to the community they sought to serve while they themselves remained in modest circumstances, there has been no listing of them that has been generally brought to notice. Paine declared the dangers of over-valuing worldly wealth while he was in Lewes, and at a time when he was actively proclaiming the hardships inflicted upon excisemen by the constraint of fixed salaries in inflationary times. His declamation on this point is one of the indications that inclines me to the view that he may well have seen himself as a possible minister inculcating the desirability of a broad rather than a narrow approach to human values. And Paine’s subsequent dispersal of the rewards from his own literary successes shows that his views were genuinely held, and not mere rhetoric.

My good friends: however difficult it may be to persuade many of you to think so, yet certain it is, that the universal veneration men have for the mineral call’d Gold is highly absurd and preposterous. To be sure it’s a useful thing in its place. It is found to be a good viaticum enough upon a journey, and to answer many other purposes in social life. But because it answers some purposes, is it therefore to answer all? Suppose it to be a convenient medium in the business of commerce, to reduce wares to a balance, is this any reason it should be made the common measure and standard of everything else? If they are, then, when we see a child in raptures over a piece of gilt gingerbread, we see a PICTURE OF THE TIMES. (Ibid. September 28, 1772.)

But Paine, like other human beings, must inevitably have been influenced at times by the happenings — and any bitter experiences — which had befallen him in person. It was possibly the injustice of his first dismissal from the Excise which lay behind his plea for proper consideration being given to matters which involved the public interest:

“When any thing is upon the carpet, in justice to the public, as well as yourself, do suspend your judgment a little; assert the distinguishing privilege of a rational being, which is, to think, before you determine; otherwise you are liable to injure society, you commit an outrage against common sense, and in so doing, glaringly insult your understanding.” (Ibid. June 14, 1773, and September 27, 1773.)

Although Paine could not have known so, these words were opposite not only to his first excise dismissal, but also to his second. Whilst the full circumstances of this second dismissal are best reserved for separate discussion elsewhere, it is consistent with the general purpose of this paper to delineate them broadly, so that the substance of new information may be recorded.

A new reading of Paine’s excise career now suggests that in early 1774 Paine was recommended for promotion by the Excise Commissioner George Lewis Scott, who has long been recognised as a patron of Paine. It may be wondered why Scott should have delayed more than a year after Paine’s visit to London to take this step, but again the Lewes Writings provide a clue, as there are indications that Paine suffered an illness — possibly serious enough to be counted a breakdown — after his return to Lewes. (Customs and Excise Library, reference.) This illness caused a break in the continuity of the Writings, and it also explains the cessation of Paine’s participation in urban affairs in 1773, although he did not leave the town until the following year.

A recommendation for promotion from Commissioner level could not fail to carry strong weight, and it would have commanded immediate attention. Paine is seen, from his known correspondence, to have been favourably disposed towards promotion, and it is conceivable — to judge by his actions — that he had been assured promotion was certain. But promotion carried an inevitable consequence; it necessitated removal from Lewes and cessation of his activities in the town. Paine accepted this. The *Lewes Journal* of April 11th, 1774, carried an announcement of the sale by auction of business and household effects near the West Gate, the sale to be conducted on April 14th and 15th. The substance of this announcement was published by Oldys; but he refrained from detailing its suffix:

F.B. The Dwelling House with a good Warehouse, Stable and pleasant Garden, to be LET and entered on immediately.** (A minor point that may be mentioned here is that the announcement spelt *Paine* with the final *e*, showing that the alternative spelling was in use before Paine emigrated.)

No indication has so far been found of how much notice was required for the insertion of an announcement in the *Lewes Journal*; it is highly probable that several days at least would have been required, as is the practice today, and it follows that the decision to quit the Westgate premises must have been taken several days before Monday, April 11th. Since the Commissioners dismissed Paine from Lewes 4 Outride on Friday, April 8th, and their decision must have been physically carried to Lewes, it is apparent that the decision to sell up the business was taken before Paine was dismissed.

What seems to be clear is that Paine was in line for promotion in March, and that he arranged to sell up his business some days before April 11th. It happened that an opportunity to contrive Paine’s second dismissal arose about this time, when his Supervisor was granted leave; a substitute official named Edward Clifford, whose movements were controlled from London, was sent temporarily to Lewes, and on April 6th he lodged a complaint that Paine was absent without leave, and imputed debt as Paine’s reason. Under the standing rules of the service, such a complaint should have been passed for investigation to the highest local official, the Excise Collector for Sussex, who was also based in Lewes town. The Collector would have been the official who had arranged Paine’s prolonged visit to London the preceding year, and he would have known Paine very well; he would have known Paine’s promotion position, he would have been personally familiar with Paine’s shop, and he would have known, in all probability, why Paine was selling up. He would in fact have been ideally placed to investigate Clifford’s complaint and to report fully upon it to the Commissioners, as was his duty. That no such investigation was made is shown by the terms of the Board’s minute dismissing Paine on April 8th:

Thomas Pain, Officer of Lewes 4th Outride Sussex Collection, having quitted his Business without obtaining the Boards leave for so doing, and being gone off on account of the Debts which he hath contracted, as by Letter of the 6th instant from Edward Clifford Supervisor and the said Paine having been once before Discharged; ORDER’D that he be again Discharged, that the Supernumerary or a proper officer supply the vacancy… (Foner, P. S., Writings, Vol. 2, p. 1131.)

Not only was Clifford’s complaint uninvestigated by the Collector, but it must have been rushed post-haste to London; otherwise it could not have been decided by the Board — or by the advising official — two days later. The wording of the minute gives no indication that Clifford was only temporarily at Lewes and had only slight knowledge of Paine; further, the minute reads as if Clifford was an established Supervisor when he was in fact an Examiner — an apprentice Supervisor employed on head office duties when not officiating for Supervisors absent on leave or for other causes. The speed with which the unsupported complaint by a temporary official at Lewes was rushed to the Board and irregularly dealt with, is strong circumstantial evidence of the desire to contrive Paine’s ruin at Lewes.

In the space of a few days, Paine, who had looked set for an advancement in the Excise, was deprived of his livelihood and robbed of his reputation in Lewes. No evidence has ever been produced that the sale of his possessions was other than voluntary, and there is no evidence that the business was not satisfactorily wound up. Oldys has told us that Paine continued to enjoy the confidence of the Commissioner, G. L. Scott, who supported his appeal for restoration, but the grounds of Paine’s appeal have never been ascertained. We know from other sources that Paine entered into legal articles of separation from his wife, whom he set legally free without dissolving the marriage; and we know Scott enlisted the aid of Benjamin Franklin to give Paine a good start in a new life in America when Paine decided to emigrate. Scott, in fact, did his very best to mitigate the disastrous results that followed his well-meaning attempt to promote Paine’s interest in the Excise.

Until recently it was believed that the first thirty-seven years of Paine’s life formed a self-contained episode that bore little relationship to the spectacular career that was to follow; the truth is far different, for it was on the experience of those years that Paine was to build, and he left clues that enable the continuity to be traced.

Paine’s personal life during his first year in America seems to be no better known than much of his early life in England, but information continues to be gathered about the structure of society in Philadelphia, in which he moved. The most detailed account to date of Paine’s early journalistic activities in America is to be found in D. F. Hawke’s biography Paine, which appears to lay surprising emphasis on scurrilous comments by Paine’s detractors, which are not impartially assessed; but Hawke, like Oldys, supplies information on some points which are not found elsewhere, and which allows an independent opinion to be advanced.

Hawke’s account of Paine’s connection with the Pennsylvania Magazine seems to me to be of particular importance, for his description of Paine’s editorial practices reveals — to a researcher who has looked through the files of the Lewes Journal — that these were modelled upon the practice in Lewes. More important, Hawke quotes the motto of the magazine, Juvat in sylvis habitare, the significance of which I think he misses. Literally it means ‘It is of use to live in the woods,’ which is surely a strange sentiment with which to launch a new magazine in an environment which has no specific sylvan associations; however, when this motto is expressed in the Paine idiom, it becomes, ‘It is useful to be A FORESTER,’ and this exactly summarises Paine’s situation on taking over the practical control of the magazine.

Paine’s letter to Benjamin Franklin dated March 4th., 1775, (Aldridge, A. O. Man of Reason, p. 41.) gives a reasonably clear explanation of Paine’s position; in it he says ‘Robert Aitken, has lately attempted a magazine, but having little or no turn that way himself, has applied to me for assistance.’ This suggests that Paine could have found himself in charge of a first number unprepared editorially for printing, and that he pulled it into shape for production; in other words that he may have played no part in the first number as a contributor, but may have edited in part. The position regarding the first number is not clear, but it may be made clearer by a detailed examination of surviving copies of the magazine. The intriguing point is the allocation of the motto to its instigator, for whereas it has no apparent relevance to the printer of the magazine or its readers, it seems to have a very clear relevance to Paine.

Increased interest now attaches to the known fact that Paine originally intended Common Sense to be published as a series of letters in the newspapers (Ibid. p. 29.) for this is now seen to be merely an intention to continue his Lewes practice of submitting regular articles for continuing publication in successive editions. Hawke tells us that Paine began journalistic activities in the first days of his American experience, and It now appears to me that Paine’s intention on emigrating to America was to continue his career as a journalist which had been well established in England. This would have been a bold intention for an inexperienced immigrant, but Paine cannot have expected to support himself by writing from the first. Ordinary prudence would have suggested an alternative approach would be necessary initially, and tutoring would have seemed a good choice for this temporary expedient. Benjamin Franklin’s letter recommending Paine to his son-in-law, Richard Bache, may be read as seeking to secure for Paine some such provisional employment:

…If you can put him in a way of obtaining employment as a clerk, or assistant tutor in a school, or assistant surveyor, till he can make acquaintance and obtain a knowledge of the country….(Lewes Journal, December 28, 1772.)

When newspaper correspondence followed the publication of Common Sense, and Paine became involved in the debate, he found himself in a similar situation that which prompted his first letter in the Lewes Journal, which had also defended the preaching of a new doctrine. While it was natural, in these parallel circumstances, for Paine to revive his first pen-name, it must also have been a deliberate decision, for by that time he had been long enough in his new environment to know how unusual the pseudonym The Forester would appear there. The minor variation in the pen-name is easily accounted for for whilst on penning his first article in the Lewes press Paine had been t one of the many local residents who could regard themselves as foresters, the success of his articles was such that he had quickly become known as The Forester, and indeed he occasionally so referred to himself in the Lewes Writings. (Ibid. November 1, 1773.) But there is another point relating to Paine’s revival of his first pen-name which is of greater interest and importance; at one time in Lewes Paine found himself being regarded as the author of many more letters to the Journal than he had himself written; this situation provoked from him a special letter to the Journal which was penned in humorous vein, but which concluded with an undertaking that Paine might have felt himself bound to respect even in his new life in America:

It is a common remark that people are seldom very fond of being called upon to father other folks’ children. And indeed I see no reason why they should. If a man provides for, and take care of his own, it appears to be all the claim the community has upon him in that respect. And yet, we find, this won’t always serve his point neither. But to come to the point. I am (it seems) the reputed, author of many Letters that have appeared in your Paper, besides what I have acknowledged for my own. Nay, at one time, not a single literary bantling could put its head into the world, but it was immediately laid to my charge. To be sure when a Hen roost is robb’d, it is so natural to suspect an old offender, that I had but little room to be angry. If the imputation was designed me as a compliment, I acknowledge the obligation; but I must confess, I am not a very passionate admirer of such compliments, because they may involve a man in difficulties, which all the friends he has can’t extricate him out of. I have no ambition to be called upon to eat another man’s words, nor to defend any opinions but my own. The maxim in these affairs seems to be, Res tuas tibi habeto, et ego habeto meas. I have made this an invariable rule. You may call mine indeed a kind of Bush-fighting, because I always take my stand in the Wood; but it deserves that name in no other sense whatever, because I have never discharged a single bolt (however wildly it might be aim’s) without first setting my mark to it. However, to guard against all misunderstandings for the future, in A MATTER OF SUCH MIGHT IMPORTANCE, I take upon me to affirm, and I can affirm it with truth, that as I never have, so I never will send any thing to the Paper, but under one and the same Signature, namely, that of

– A FORESTER. (Foner, P. S., Writings, Vol. 2, p. 463.)

There is an obvious implication in Paine’s (presumed) respect for this Lewes Journal undertaking that his American writings might have been known – or were expected to become known – to some of his friends in Lewes; there is some evidence that he kept in touch with Lewes whenever he could. We know for certain that Paine read the Lewes Journal when he eventually returned to London, for he clearly stated as much in his letter to the Sheriff of Sussex dated June 30th., 1792; (Lewes Journal, July 9, 1792.) (this letter was produced at the meeting in the Town Hall at Lewes, but was ‘cast unopened upon the table, and torn to pieces with distinguished marks of contempt,….’ but not without some sounds of protest from the assembly) (Ibid. January 25, 1773.) In my view, Paine deliberately linked his old and his new journalistic careers by his revival of the Forester identity, but he did so in a manner which did not make the link immediately apparent to his contemporaries, although the connection is clear to any impartial researcher in our own day.

Another point of interest is that Oldys described the American Forester letters as written by A Forester, although – since he was a student of American newspapers – he might have been expected to use the later form of Paine’s pen-name. Since Oldys had access to Paine’s excise records, which probably detailed Paine’s literary activities in Lewes, it is likely that Oldys was aware of the Lewes Writings, but preferred not to publicise them. Yet by using the first form of the pseudonym, he put himself in a position to defend his own reputation as a researcher if he ever needed to.

Discovery of the Lewes Writings seems to me a major advance in our knowledge of Paine, but their impact is bound to vary from reader to reader, for, as is to be expected of the early work even of so gifted a writer as Paine they differ in subject matter, in style, in interest, and in importance. My own impressions, as set out in this paper, can only be presented as starting points for further consideration. Within this context, I may perhaps be permitted to record that on first perusing them I reflected that possibly the most important single item therein is a short passage in which Paine describes his approach when seeking to convert a man to a fresh opinion:

….but one thing I seem to be clear in, viz. that the best way to convince a man, or (if you make a metaphor of it) to conquer him, is to meet him in his own way, and fight him with his own weapons. David might well say of the arms they furnished him with, “I cannot go with these, for I have not proved them.” People do not love to have instruments put into their hands which they have not been used to, they always seem awkward to us, and ’tis but natural to throw them away with disdain. (Foner, Eric. Tom Paine and Revolutionary America, pp. 111–13.)

These words, like much of Paine’s writing, seem to express the opinion of a simple man, but the thinking behind them is profound. I think they embody the secret of Paine’s vast popular appeal, and show his blending of many sources of experience into his advanced technique of persuasion. Who could have learned better than the exciseman who never needed to refer a contentious matter to the Lewes Justices that the way to overcome a trader’s reluctance to pay revenue was to reason with him from his own point of view? Who but a man who loved ‘to see human nature in all its shapes’ and who was familiar with manual practice in many trades, would have appreciated the general reluctance to accept unfamiliar tools (and novel ideas) thrust into unwilling hands (and minds) by misguided well-wishers, and the astonishing results that could be achieved by adapting familiar ones to new circumstances? Who could know better than an itinerant lay preacher the force of biblical precepts aptly quoted to match a human situation and resolve a human dilemma? And who knew better than Paine, the architect of social democracy, the number of potential Davids in any worthy community capable of emerging as giant-killers when effectively called to battle?

With hindsight, it is now possible to see Paine’s technique employed even in his first letter to the Lewes Journal, but the finest example of Paine’s mounting an argument for change from the standpoint of his audience must surely be Common Sense. And Common Sense is a masterly display of the Methodist approach being adapted to a secular situations Methodism had been popularised in America, not by John Wesley, but by George Whitefield, whose vigorous Calvinistic preaching ignited the religious fervor of the American settlers, during the period known as the Great Awakening. Eric Foner has related that the evangelical religious fundamentalism flowing from that time was still a potent source of the social climate Paine found on his arrival in the New World. (Foner, P. S., Writings, Vol. 1, p. 12.) In Common Sense, after stating the broad outlines of his subject, Paine launched into strong biblical declamation. He thus met the ordinary Americans in their own way, and he fought their conservative reluctance to break with monarchical government with their own familiar weapons of biblical quotations:

Paine may well have moved away from the religious attitude he adopted in Common Sense in his own thinking, but it was not his object to present his own current religious views in his anonymous pamphlet; yet it is to be carefully noted that when punching home the message that the Almighty had entered a divine protest against mon- archial government in the scriptures, he presented this not as a single conclusion, but as one of two possible conclusion, the alternative being ‘or the scripture is false.’ (T.P.S. Bulletin, No. 1, Vol. 6, 1977, pp. 5–19.) Paine was not at that time the only advocate of American independence, but he was the only one with sufficient understanding of ordinary people coupled with the essential gift of lucid rational exposition, who was able to lead them towards indep- endence from their own positions, which were their inevitable starting points when he brought them into the political debate. Thomas Paine, who seemed to some American leaders to be a man of inferior intellectual talents, was in fact already the master of psychological warfare, an advanced technique scarcely dreamed of in those days. Paine not only understood its basis, but was its skilled and experienced practitioner; his enemies could never forgive his clearer vision of social democracy, and his greater wisdom in applying it to the purpose he was immediately concerned with.

Paine’s technique in seeking conversion, as he set it out in the Lewes Writings at the outset of his career, explains the great difference in approach in the first and second parts of The Age of Reason. The first part was specifically aimed at the growing band of French atheists who had already rejected dogma and placed their faith in reason; Paine started from their chosen ground and wrestled with them on the basis of of the incontrovertible evidence in the heavens above as explored and interpreted by their own new priests, the scientists of the day. When the practitioners of orthodoxy became sufficiently alarmed to enter the debate from a different point of view, and on the quite different premises of biblical authority, Paine accepted their challenge; he wrote the second part on the basis of the ground chosen by his challengers, and he fought them with their own chosen weapon – the reliability of scriptural writings.

Discovery of the Lewes Writings will inevitably revive, and in more acute form, the question why Paine disclaimed writing in England. Since no evidence has emerged that Paine benefited financially from them, the Lewes Writings do not diminish the previous suggestion that Paine was merely denying writing for pecuniary profit. I do not find this suggestion convincing, and I suggest that a more positive approach to the problem is to consider the position which would have arisen if Paine had acknowledged his English writings. He would then have identified the author of Common Sense as an exciseman from Lewes who had produced the Lewes Writings and the Case of the Officers of Excise, both of which were known to the Establishment.

The inference seems to be that he was concerned to avoid being so identified, and it appears that he may have been successful in this endeavour until the publication of Oldys life many years later. Since Paine himself would have had nothing to lose in America by such identification, my conclusion is that Paine sought to avoid a resulting consequence which would not have fallen upon himself, but upon his wife and parents left behind in England. In other words, Paine was already a political refugee at the time of his emigration, and – like similar tragic figures in our own times – he was concerned to shield his relatives back home from persecution in revenge for his contribution to the American Revolution. Paine’s wife would have been particularly vulnerable to officially-inspired abuse, and it could have been to minimise this possibility that be set her free before emigrating; and we know from the persistence of the anti- Paine lobby in Thetford that his parents could have been made very uncomfortable indeed in their old age.

Paine’s position on his-return to England was quite different. He was then a famous: and influential American citizen, whom the Establishment would not attack until it managed to diminish his stature, a manoeuvre which was attempted by commissioning Chalmers to write the Oldys biography. And it is quite clear that Paine still continued to shield his associates, and set himself to draw the recriminations of the Establishment onto himself alone. It almost seems that – he courted martyrdom, perhaps because he could see no other effective way of impressing his case upon history. That he changed his tactics was due to the introduction of a new factor into the situation which offered him a chance to play a continuing part in the events which were changing the Western World, Achille Audibert arrived in London to acquaint Paine that he had been elected as representative for Pas de Calais,. and Paine accompanied Audibert back to France to continue his career on the world stage as a member of the French Convention.

To readers who find difficulty in crediting that an exciseman and his family could become subject to persecution in England, I offer a single cold legal fact. Two centuries of continuing human progress were necessary before the Age of Human Rights arrived; the Parliamentary Commissioner Act of 1967 then empowered an English Ombudsman to enquire into action taken on behalf of the Crown. But the Act incorporates a third schedule which excludes from its benefit a vast range of public servants, including excisemen, no matter how gross the maladministration practised against them is claimed to be. This schedule is conveniently forgotten when the clamour arises for Human Rights to be respected in other countries. Yet were this Principle of exclusion from protection of individuals directly under the contract of the State, to be restated in kindred terms in the legislation of monolithic societies, complaints of abuses against individuals in those societies would be ruled out of court by the precedent of the legal provisions of the United Kingdom! This is a sobering thought which others are free to debate and to contest; but, in the words of A FORESTER, “no controversy, let matters go as they will.”