By George Hindmarch

“Magna Carta is the first corporate act of the nation roused to its sense of unity.” “The na- tion in general, the people of the towns and villages, the commons of later days….had now thrown themselves on the side of the barons.” “The people….for the first time since the Conquest ranged themselves on the side of the barons against the king.

– William Stubbs, author of Constitutional History of England (3 vols), 1873-8, as quoted by Edward Jenks in his paper, “The Myth of Magna Carta” (1904).

STUDENTS OF THE life of Thomas Paine have long been familiar with the wide-spread distortion of fact used to misrepresent his personal character and message, and posterity owes a continuing debt to Moncure Conway for his dispersal of the smokescreen contrived by ‘intimidated historians’ to hide Paine’s true nature from later generations. But Conway’s exposure of the misrepresentation of history has much wider application than the life of Paine, for in order that the intended defamation should be effective and effective it was for a long time it had to be broadly based.

Recent reading by the present writer now suggests that the propaganda directed against Paine, linked as it was with efforts to counteract early favourable reactions to the French Revolution, included in its scope misrepresentations of earlier periods when the continuous struggle for human rights similarly found expression in public unrest. Of these the most important is the famous confrontation of King John by the barons at Runnymede in 1215, but the confrontation of Richard II by the peasants headed by Wat Tylor at Smithfield also figures prominently. A linking of Paine’s name with the, conventional presentation of the events at Runnymede, which took place more than five hundred years before Paine was born, may appear startlingly unorthodox, but the connection is clear enough to justify the outlining in the present paper of the path to Runnymedd, and the drawing of parallels between two victims of major historical slander, King John and Thomas Paine.

However, since an understandable immediate reaction in the reader’s mind could well be that this thesis is untenable in view of the time-gap of five centuries between the two periods under consideration, it is appropriate to draw attention to a little known fact which clearly indicates how strongly the popular presentation of Runnymede has been conditioned by influential 18th century opinion. The authority for this revelation is the eminent legal commentator, Sir William Blackstone, who, when publishing The Great Charter and the Charter of the Forest in 1759, a year when Paine was 22 years of age, disclosed that the terms of the Runnymede charter had never previously been set before the public. Indeed, as we are now able to see, its terms remained unknown, even to the most erudite of historians, for more than four hundred years after the great gathering at Runnymede had dispersed. Blackstone’s opening words to his readers were:

There is no transaction in the ancient part of our English history more interesting and important than the rise and progress, the gradual mutation, and fi- nal establishment of the charters of liberties, emphatically styled THE GREAT CHARTER AND CHARTER OF THE FOREST; and yet there is none that has been transmitted down to us with less accuracy and historical precision. There is not hitherto extant any full and correct copy of the charter granted by King John.

The character of King John has suffered from misrepresentation even longer than that of Thomas Paine, and as with Paine – a major reason for this injustice has been the revenge taken by the established church, for John continued the process of diminishing excessive ecclesiastical privilege which his father had pursued during his clash of wills with Archbishop Thomas Becket. The early church wielded such enormous secular influence that a priest could commit the most heinous crimes without facing trial in lay courts; such a criminal churchman was answerable only to the church itself, and it was this legal absurdity which was the root of the struggle between Henry II and Becket. This ecclesiastical privilege can now be set into historical perspective by a twentieth century parallel; Paul Scharfe, legal head of Hitler’s SS, declared that, no State Court… had the right to judge an SS man; this was the sole prerogative of SS judges and SS superior officers!1

Stephen Langton, Archbishop of Canterbury and chief ecclesiastical opponent of the king during the civic unrest in John’s reign, was appointed by Pope Innocent III over the head of the King. Langton knew little of England, having spent most of his adult life acquiring fame as a scholar in France and Italy, and his appointment was resisted by John until the long dispute between king and pope was resolved through the efforts of a special papal emissary, Pandulf, who thereafter figured prominently amongst John’s entourage. Innocent, who thus acquired a permanent highly-placed representative at the English court, learned in the ensuing years that he had made a serious mistake in appointing Langton, and he endeavoured to minimise the consequences of his error during the last part of his papacy by holding Langton indefinitely in Rome. But the death of Innocent on July 16, 1216, shortly before the death of John on October 18, 1216, permitted Langton to resume his position as overlord of the church in England, and to exert tremendous pressure on church functionaries; these later included the authors of manuscripts long accepted as authentic annals of the 13th century, but now largely discounted. In John’s day, churchmen enjoyed a near-monopoly of literacy, and even merchants trying to set up commercial records needed their assistance, a circumstance which caused the word clerk to denote both bookkeepers and churchmen. By a quirk of history there was no annalist active during John’s reign, and the ecclesiastical annals were compiled after his death by cloistered scribes lacking personal knowledge of the major events of the reign, who set down accounts fed to them by visitors to their monasteries. A well-known example of their virulence is the comment of Matthew Paris, a monk of St. Alban’s:

“Foul as it is, hell is defiled by the fouler presence of John.”

It has not been until well into the 20th century that the prejudices against John implanted by Matthew Paris and his ilk have been outgrown, but even today it does not seem to be generally appreciated that their excessively-biassed accounts cannot rationally be regarded as distorted only when speaking of the king. The re-appraisal of John, now in progress, needs to be accompanied by a complementary re-appraisal of his chief opponent in England, Archbishop Langton.

Henry II, first of the Angevin kings. of England, hailed from the French pro- vince of Anjou, and already ruled over other major areas of France when he completed his Angevin empire on absconding the throne of England after the death of King Stephen in 1154. John was Henry’s youngest and favourite son, born unexpectedly to a queen in her mid-forties after Henry, believing his family to be complete, had already allocated his empire amongst his older sons. Thus John, in infancy, was dubbed Jean-Sans-Terre, which historians have translated and preserved as John Lackland, although it was a foolish sobriquet with which to burden a future king who by the age of nine had become one of the greatest land-owners in his father’s dominions. Henry II is recognised as one of the great kings of England, specially notable for his introduction of a nation- wide system of common law which progressively supplanted feudal law as it was carried into the shires by travelling judges appointed by the king for this purpose. By 1181, by his Assize of Arms, Henry made another notable advance in the social progress of Englishmen by conferring upon the small but steadily- growing class of freemen en enhanced status. Henry required every freeman to furnish himself with arms and hold himself in readiness tó support the royal standard if called upon to do so, thus creating a new national militia (with greater substance than the ancient Saxon fyrd) which the king could call into being in any area of England where he needed temporary armed support.

This new militia was summoned directly by the king through his own royal officials, the sheriffs of the shires, and it was thus quite distinct from the feudal levies which the lords of the manors could raise. Henry’s subsequent summonses gave his freemen military experience, and he ensured the permanence of their martial spirit by requiring them to bequeath their arms to their sons. Feudalism was never notable for inculcating national spirit, for its kings were sometimes little more than the strongest amongst many nobles, who could not easily dissuade groups of their erstwhile followers from forming opposing armed camps. English barons, who already chafed under the greater feudal power acquired by William I on parcelling out England after the Conquest, and the diminution of their local power as feudal law declined under Henry, were now further disquieted by the emergence of an independent permanently armed yeomanry in areas they had regarded as their personal preserves, John, who spent much time with his father, probably received special tutelage in Henry’s policies and their application, and he too called upon this militia in times of need. Thus in 1213, only two years before Runnymede, he called out the freemen of the southern counties when he was girding England against a possible French invasion. But there was to be a gap of ten years after the death of Henry before his favourite son took his place, and those years witnessed the very different regal policies of Richard I.

The brothers Richard and John were as different as they have been depicted, yet neither king has been accurately described in popular history: While John has been held to typify all that was evil, Richard has been lauded as the embodiment of chivalry, but the mask of chivalry hid an ugly face. At Acre, during the crusades, Richard callously butchered more than two thousand hostages in sight of the Saracen tents, and in England he hanged Englishmen in front of Nottingham Castle to induce its garrison to surrender. During his ten-year reign he spent only a few months in England, but inflicted continuous harsh taxation upon the English to fund his military adventures abroad. To raise money, he sold every property, office and privilege for which he could find an affluent buyer. Scotland bought independence from him for ten thousand marks, and whole counties of England were sold for exploitation by their purchasers. It is to his reign that tradition understandably attributes the exploits of the legendary Robin Hood against the oppressive sheriff. But the heaviest levy the English people ever endured was inflicted on them after Richard, through foolhardiness, had allowed himself to be captured; then every Englishman of substance suffered a levy of one quarter of the value of his goods and rents, as a contribution towards the king’s ransom.

Consequently, John inherited the crown of England along with the vast resentment provoked by Richard’s excessive taxation, and baronial resentment included opposition both to military service abroad in the service of the king, and also to payment of soutage (or shield money) which had become the traditional alternative payable in lieu of service in arms. It was John’s demand for scutage in 1214, a demand quite legitimately made in accordance with the customs of the times, which was to be the spark causing the long-smanouldering resentment of the barons to flare up in a revolt by a minority of their number.

John was a capable and successful military commander, who also displayed great naval foresight by laying the foundation of the future of the future Royal Navy. He shared the fierce Angevin temperament, which could find expression in outbursts of violent rage as well as in energetic and determined pursuit of an aim, but first and foremost John was a negotiator who did not resort to force unless he had exhausted the possibilities for resolving difficulties by peaceful means. This characteristic earned him another nick-name from his barons, John Softsword; centuries later another famous national leader was to epitomise this attitude: jaw-jaw is better than war-war.

John soon had good reason to feel pleased with his policy of diplomacy, for at the end of the first year of his reign he seemed stronger on the continent than Richard had appeared after ten years of conflict. John now turned his attention to England, and at once embarked upon a new pattern of kingship. His novel technique called for greater contact and confidence between monarch and common people than had ever previously existed; John achieved this by long journeys across the length and breadth of his kingdom in all seasons of the year. His subjects soon became aware of the greater royal interest in their lives, and they quickly reciprocated; when John elected to sit on the bench of local courts along his way, his initiative drew numerous appeals from his more humble subjects as soon as it became known that small disputes as well as great ones could now be submitted to royal jurisdiction.

John’s extensive and arduous journeys could not have been accomplished had he remained burdened with the extensive train of royal officials who had accompanied previous kings. John, therefore, hived off many officials to permanent quarters in London where they employed the Great Seal to authenticate degrees issued under his directions; he introduced a small Privy Seal for business personally conducted in the shires. Because he fully appreciated the need to retain adequate supervision of the newly separated bureaucracy, he required the permanent officials to keep detailed records on permanent rolls which he scrutinised on his return to London. It is from modern study of these rolls a much more demanding task than facile reading of distorted annals that reassessment of John’s kingship is being made. And these new studies have revealed that John employed a system of authenticating important instructions by confidential countersigns known only to himself and his trusted dignitaries; for obvious reasons these were not written down, and we have learned of them only because occasions arose when they could not, be operated as arranged, but were operated inversely by being overtly declared and cancelled; thus John might order that a messenger need no longer produce a pre-designated royal ring before an instruction was put into operation. The importance of this royal and secret system cannot be over-emphasised in consideration of the later events of John’s reign, notably Runnymede, for it means that John had ample time during the earlier stages of the dispute to arrange with key sheriffs that any instructions issued under duress (or other circumstances rendering them illegal) would not be put into practice unless confidential counter-signs, unknown to the rebels, were also employed by the king. John used this system from the early days of his reign, and that he did so is another example of his exceptional administrative skill in the particularly difficult art of kingship in feudal times, when the loyalties of lesser nobles were notoriously fickle.

Feudalism operated through interlocking alliances at all levels of society, cemented by paths of fealty. These had first been devised in an endeavour to combat invaders, such as the early Vikings, but in later times the more important feudal alliances arose from military truces, and reflected the balance of power at the cessation of hostilities. Such feudal arrangements persisted as long as that balance lasted, but when a lesser party saw a promising opportunity he frequently revoked his oath, and the greater party would then attempt to re-impose a new agreement under a fresh oath. But continually changing local relationships could make this process lengthy, and sometimes centuries passed before a major relationship could be effectively restored.2

Henry IIs vast possessions in France came to him through parentage and marriage, and the conventional term Angevin empire is misleading; he was no emperor, but ruled each of his separate French provinces individually as a duke or count, and he owed fealty for every one of them, directly or indirectly, to the King of France, whose over-riding ambition was to regain control of them all and re-unite France under direct royal authority. Henry’s great problem, which his sons inherited, was to maintain control of each separate province although necessarily absent from it for long periods during which unrest was skilfully fomented by the French king. During the long contest of royal ambitions, meetings took place from time to time between the rival kings to re-negotiate their feudal relationship; but the tide of history flowed with the kings of France. Although nobles and knights would rally behind their liege lord to repel an invader from their home territory, they increasingly declined to support him in regions other than their own, and this growing resistance was a European phenomenon, influencing · French nobles as well as English barons. No-where was its effect to be more strikingly illustrated than in Normandy, notwithstanding its strong historical ties with England.

In the year 911, Charles the Simple, King of France, had ceded control of the province to the Viking chieftain Rollon under the treaty of St. Clair sur Epte which established Rollon as Duke of Normandy, but as a vassal of the King of France. Strong resident Norman dukes had no difficulty in retaining their dominant position, but after the Conquest the personal authority of the duke and chief nobles became much more variable as the affairs of England and other autonomous regions absorbed more of their attention. By Angevin times, the duke was no longer Norman, and his forces were increasingly mercenaries who further estranged the Norman people, and correspondingly strengthened the old attachment to the French crown. It was John’s lot to be Duke or Normandy when increasing rever- sion to the French cause tipped the balance, and restored to Phillip Augustus in 1204 the province wrested from the French king three centuries before.

No one saw more clearly than John the trend underlying his loss of Normandy; no one appreciated more keenly than he the need to re ?n the loyalty of his nobles if his position elsewhere was to be retained. Preservation of his nobles’ oaths of fealty became his over-riding concern; he watched vigilantly for signs of disaffection and strove to remedy any justified grievances; any rebel who resumed fealty was generously welcomed back into the fold. In the international field too, co-operation became his strategy, as he showed when he endeavoured to stem the tide of French success by engineering a pincer movement against the French king which merits an important place in the history of English military development. John himself headed a successful campaign from Poitou, but his allies failed in the complimentary offensive through Flanders. Once again John conferred as a great French noble with the King of France, and returned to England with the promise of five years peace between them. He was to devote the rest of his life to an endeavour to unite the English people behind their king in an increasingly just society with greater human rights for all.

It was to be the tragedy of John’s reign that his vision of the new England was to be anathema to a minority of his lesser nobles, who could envisage nothing finer than a land of small domains where the common people lived as serfs of the lords of the manors. Dissident nobles, honk after greater privileges protected by royal guarantees against reform, and further bolstered by feudal powers to coerce upstart serfs in their own local courts. One of the great thorns in their flesh was the presence of the independent armed freeman, whom they yearned to reduce to subservience to themselves if they could. But a freeman now enjoyed a water-tight legal defence against the re-imposition of serfdom; once he had taken his oath to the king as a member of the royal militia, no noble could set aside in a local court the freeman’s royally sanctioned independence.3 And it was to become a major objective of the rebel barons to force the king to abandon his direct link with the freemen, and to make him order them to transfer their allegiance back to the local lords.

As individuals, rebellious barons could do very little against the strong Angevin king, and before they could muster effective opposition as a group they needed an astute and determined leader. Such a leader was supplied unwittingly by Innocent III in the person of Stephen Langton. For years Langton had been excluded from Canterbury by John’s opposition, and in the course of time his resentment against the king had hardened into hatred; once Langton donned the archbishop’s robes after the reconciliation between John and Innocent, he lost no time in organising the baronial resentment against the king. Innocent realised in time that the baronial revolt against John had taken on substance only after Langton had acceded to Canterbury.4 He was later to suspend Langton from office, and was dissuaded from dismissing him only by the influence of senior papal advisors. But it took considerable time before a pope could be convinced of the necessity to reverse an attitude previously supported with. tenacity, and during the period of time necessary for Innocent to change his mind, events occurred which have been amongst the most misrepresented in English history.

It is likely that John saw from the outset of his new relationship with Innocent that admission of Lanton to Canterbury involved a serious threat, for he followed up the reconciliation with a swift master-stroke, which makes strange reading to modern eyes; as King of England, John voluntarily surrendered his realm to the pope, receiving it back in fief as a papal vassal. To understand the brilliance of John’s manoeuvre, it is necessary to appreciate that the feudal oath he exchanged with Innocent’s proxy, sub-deacon Pandulf, cemented a feudal alliance which bound Innocent to support John equally as it bound John to support Innocent. In John’s day there was nothing unusual in a ruler being a vassal; Henry II, Richard and John were all vassals of the French king, Henry had been a vassal of the pope as had been Willian the Conqueror, and a few years earlier the supposedly indomitable Richard the Lionheart had surrendered England to the Emperor of Germany in fealty, as part of the price he paid for release from captivity.5 All the barons of England already accepted the pope as their spiritual overlord, and none saw cause to object to the new relationship entered into by John. Pope and king both faithfully complied with the terms of their reciprocal oath, and to assist in the smooth operation of this co-operation, Pandulf, the Pope’s proxy, seems to have been given a special commission which enabled him to shuttle between London and Rome as a confidant promoting continuous understanding and co-operation.

The great world-wide importance accorded human rights in our own day has tended to represent the struggle for personal liberty as a characteristic of the 20th century, but in England individual liberty has been the subject of a continuous struggle stretching back into our history. Anglo-Saxon kings had sworn a tri-partite coronation oath promising their people just government, and the Norman kings had continued this practice. At the beginning of his reign, Henry I issued the first charter of liberties which has survived in English constitutional history; it is not an extensive document, but is notable for regal promises to quash all ‘evil customs’ and revive the legal standards of Edward the Confessor, who had come to be regarded by nobles smarting under the Norman yoke as the embodiment of a just ruler. Although this early charter had survived in English archives, few English nobles would have been familiar with its terms during the next hundred years during which illiteracy was normal even in the higher ranks of laic society; and when Langton theatrically flourished a copy before an assembly of the discontented barons, the emotional appeal of a sentimental return to the halcyon past, with all evils customs abolished, had a great effect upon his dupes.It was to be a little while before they realised this document, which few except the archbishop could read, promised them little beyond an obligation to serve their king in arms in return for freedom from taxation borne by non-military subjects. But it provided an excellent starting point for their deluded campaign against John,for in the selfish view of both ecclesiastic and laic lords, John had introduced ‘evil customs’ which certainly had not been practised in the days of Edward. For example, when assessing (in accordance with the reconciliation agreement) the financial compensation due to the church for revenues from vacant sees, who could say from personal experience the true extent of losses suffered. Even worse, the ‘wicked’ king had decreed that his Great Council of the (word lost) should be enlarged by the admittance of lesser men from each shiro to proffer advice to the Crown; to some historians, this order of John’s dates from the beginning of English parliamentarianism, but to the reactionary barons it introduced an ‘evil custom’ of unparallelled magnitude which threatened the very basis of their entrenched privileges.

When John retumed from Poitou in 1214, and demanded scutage from those nobles who had declined to follow him in arms a perfectly legitimate demand by accepted practice the dissidents, schooled by Langton in the king’s absence, refused to pay, and some of their representative insolently appeared before the king in full armour. John could easily have responded to their show of armed resistance by crushing them by force, as his father had crushed previous revolts; but John was not seeking their humiliation, but their allegiance. He played for time, hoping for reconciliation through two sided discussion, and there ensued a lengthy period of negotiation conducted by intermediaries, amongst whom Langton was prominent; and the barons became increasingly truculent under the archbishop’s influence. John, reading the signs. with his customary acumen, further strengthened his claim on papal support by taking the cross as a crusader. Just as British servicemen were guaranteed their jobs when called to the colours during the second world war, so a crusader was guaranteed retention of his domestic situation by the Church; respect for this papal guarantee throughout Europe had been a major factor in saving Richard I from the loss of his continental domains during his absence abroad. Communication with Rome was conducted by the rebels also, but they were not interested in following the pope’s advice that they should resolve their differences by arbitration under papal chairmanship, an offer which John made to them.

The minority of the baronage which had rebelled against the king assembled in arms carly in 1215 and sent demands which he dismissed as calling for his surrender of his crown. Under a leader grandiloquently styled Marshal of the Army of God and Holy Church – an indirect admission that they were ranged behind Langton since Innocent certainly did not support their insurrection, they marched against Northampton Castle, and impotently squatted before its walls for weeks before moving to another castle held by a sympathiser who opened its gates. In search for easy revenues, the rebels now headed for London and its warehouses, and now they met with a stroke of great good luck the wealthy London merchants saw no profit in waging civil war in defence of the king, but discerned the prospect of tax-reduction if they joined the rebels in a joint attempt to limit the king’s power to demand revenue. Secret emissaries from the merchants informed the barons when the gates of London would be open, and the rebels marched unopposed into the capital, Thereafter the Mayor of London figured amongst the rebel leaders, and reduction of royal power to tax London and other towns was added to the list of rebel demands.

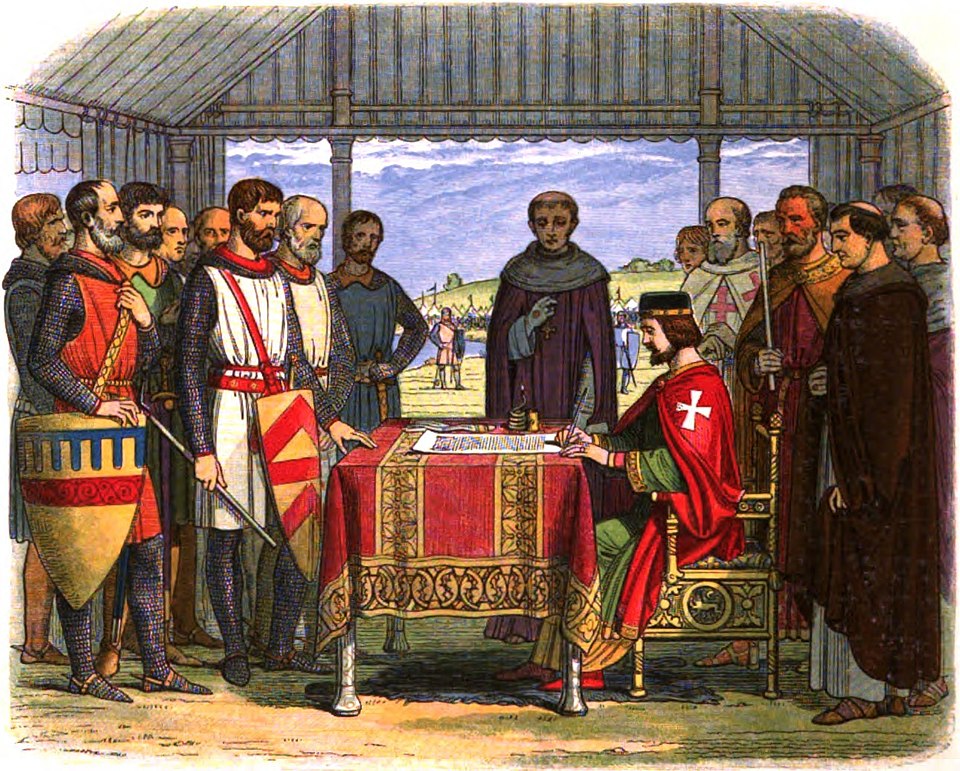

John was never again to enter London, and in his chancery there, took into his hand his Great Seal of the Kingdom. His Great Seal disappeared; how, when and why, remained unanswered questions. John bided his tino quietly in the shires, still the undisputed ruler of the majority of the baronage, and the great bulk of his people; and there he had ample time to arrange with trusted sheriffs and other loyal subjects whatever safeguards and secret counter-signs he deemed necessary. He sent an invitation to the rebels to meet him at the ancient consulting field of Runnymede, and after some delaying they came – supported by a host of thousands. John met them with only a handful of advisers, and then by force of personality and brilliant kingship won a great victory for his people. He even turned their vast military strength into a factor telling against them, for the enormous disparity in numbers ensured that in any future impartial appraisal of the outcome John might be held to have been constrained by the illegal use of force to make the concessions he granted in the course of feudal bargaining.

A digression is now necessary to comment on two important factors in the situat- ion which have received scant attention in conventional accounts. The first is the special role played by Pandulf, the shadowy papal diplomat so influentially placed between king and pontiff, whose name occupies an important place in the documents of Runnymede. It was Pandulf who was to suspend Langton, and later defeat him in an argument before the pope in Rome. In 1214 Pandulf had been appointed bishop-elect of Norwich, but reluctant to put himself in a position subservient to Langton caused him to delay taking up his appointment for many years. No biographer has yet risen to the challenge of adequately presenting the career of this remarkable man, whose origins remain obscure, but who was to rise to become the effective (and highly efficient) ruler of England during the minority of John’s son, Henry III. Pandulf died in Rome but so strong was his connection with England that his body was carried across Europe to interment in his own cathedral of Norwich.6 We need to know a great deal more about Pandulf, the pope’s proxy, and of his communications with Innocent, both by letter and in person, before an adequate account of the Runnymede saga can be written.

The second factor is the curious history of the documents of Runnymede, which were never invested with legal authority, but are of great importance as witnesses to the magnificent battle waged by John to advance the social security of his common people. These documents survived partly through luck, and partly through the activities of Sir Robert Cotton, one-time M.P. for Thetford, the birthplace of Thomas Paine. Cotton achieved such a great nation-wide reputation as a collector. of historic documents, that any which turned up were sent to him almost as a matter of course. And in due time his collection was passed to the British Museum at its foundation in 1753.

On January 1, 1629, Cotton received from a certain Humphrey Wyems, of the Inner Temple, the first copy of John’s charter to turn up; where it had lain for the past four hundred years is not known. In 1630 he received from the Warden of Dover Castle a second copy, which bore what seems to have been a small seal, perhaps John’s Privy Seal, but after surviving the centuries without damage it was rendered ille- gible by a fire in Cotton’s which melted the seal into an unrecognisable Both these copies had amendments added below the main text, but two further exemplifications which were later found in cathedral archives at Lincoln and Salisbury had the amendments fully incorporated into the text which was more carefully written, presumably by scribes no longer writing under pressure. But the Salisbury copy soon disappeared again, and Gilbert Burnet, bishop of Salisbury, who had been granted special facilities to pursue his own historical studies, was suspected of purloining it. But Burnet had come into possession of another, and more important document, now known as the Articles of the Barons; it is permanently exhibited in the British Library, but there is no known corroboration of the general belief that the impression of John’s Great Seal which is exhibited beside it was originally attached at its base.7

One further important document has surfaced; it remained in oblivion for so long that when it was found in the Public Records Office in London in 1893 it was called The Unknown Charter of Liberties. The title was apt, for it had been published in France thirty years earlier, yet remained unknown to English historians who had always neglected John’s continental position in their pursuit of him as the evil English king.

Thus there are four main documents that figure prominently in the Runnymede story the originating Charter of Liberties of Henry I, which has always been available to scholars, and the three main documents dating from John’s reign, the Unknown Charter, the Articles of the Barons, and John’s Charter, which were all lost for centuries and have been rediscovered in reverse chronological order. The present paper enjoys the great advantage of treating them in their correct order.

The reality of their situation had begun to dawn upon the rebels as they squatted impotently before the walls of Northampton Castle, passing the weeks in gloomy assessment of their weak military position, and discussing possible sources of support. Whilst help from Scotland and Wales was welcome, by far the most effective ally in the field would be Phillip Augustus, the king of France, who was known to have prepared an invasion of England only a short time before. But Phillip now needed an inducement before he would revive his plan of invasion, and so to the French king went the Unknown Charter as an indication of the concession the rebels hoped to wring from John, and the benefits such concession would confer on Phillip. Of particular interest to him would have been limitation of the rate of scutage levied to fund John’s war chest, and restrictions of baronial support to armed campaigns in Normandy and Brittany. Such constraints on John would greatly have increased Phillip’s chances of regaining regal control of the regions of France still held by John. But Phillip was precluded from supplying armed assistance to the rebels (no matter how fervently he wished them success), by the papal guarantee to crusaders which required him to respect John’s position at the time of donning the Crusaders’ Cross.

The style of the Unknown Charter is of considerable interest. It is prefaced by a copy of the Charter of Liberties of Henry I, and then begins, ‘Concedit Rex Johannes…..,’ which may be translated, ‘King John concedes…. Thus the Unknown Charter, as in the Charter of Liberties of Henry I which served as a model, the king speaks in the first person singular, but the royal plural had become standard legal practice during the reign of Richard;8 the Unknown Charter, therefore, was not drafted by a hand versed in the legal terminology used in John’s chancery.

As negotiations between king and rebels continued, and particularly after the unexpected surrender of London gave the rebel confidence a temporary boost (which induced them to issue an unsuccessful nation-wide appeal to uncommitted nobles and towns to join them in revolt), the Unknown Charter was displaced as the expression of rebel aims by a more exhaustive document which increased its scope as the arguments developed. It was drawn up. by a more clever mind, and written by a more practiced scribe. From its separate heading (usually translated as ‘these are the Articles that the barons seek and the King concedes’) this document has acquired its conventional title, The Articles of the Barons. It is a very informative document which, to date, has been too little studied.

There are several distinctive features of the Articles which mark its difference from the prevailing form of charters. It is a lengthy strip of parchment, 21 inches long and 10 inches wide, and whereas charters were written in a continuous text without paragraphs, the Articles comprises forty-nine separated items; they are unnumbered, but nowadays are usually treated as numbered in sequence, for ease of reference. The handwriting appears uniform, but the ink varies in intensity from one section to another, strongly suggesting that the document was built up by the addition of groups of items over a period of time. The calligraphy is good, and the Latin scholarly, but again the style is not that of John’s chancery, for the king is made to figure in the third person. The probability is that the document was prepared by a scholar who had not kept in touch with the development of English regal expression. Stephen Langton, who had been out of England when the royal plural was introduced during Richard’s reign, is a strong candidate for authorship, but the text may have been inscribed by one of his scribes at his dictation.

The most important feature of the Articles is a considerable gap near the bottom, beneath which appears only one item, the last; this is the ‘security clause,’ set at the base to ensure that it covered all the items which might be inscribed above it. The addition of further ideas ceased before the available space had been used up, and this gives an important indication of the point in the argument between king and rebels at which the phase represented by the Articles reached its conclusion. The security clause obviously was inscribed at an earlier date, for had it been the last item to be written there would have been no gap above it.It is a long and complicated clause, produced by much thought and careful choice of words, and designed to ensure that it remained applicable in a variety of subsequent circumstances. Its importance is very great indeed as an indication of the rebel position before the confrontation at Runnymede was arranged, yet it has rarely been reproduced in a form comprehensible to the general reader. It would certainly be an instructive exercise if it could be ascertained what percentage of the readers of the present paper were previously familiar with its terms, and for this reason it is here reproduced in full in translation:

This is the form of the security for observing peace and the liberties between the king and the realm. The barons shall choose twenty-five barons of the realm, whom they will, who should with all their power observe, keep and cause to be observed, the peace and liberties which the king mth granted, and confirmed by this charter; so that if the king or his justiciaries, or the king’s bailiffs, or any of his servants, offend against any one in any particular, or transgress and of the articles of peace and security, and the offence be shown to four barons out of the twenty-five aforesaid barons, these four barons shall go to our lord king or his justiciary, if the king be without the realm, declaring to him the misdeed, and they shall pray of him that the misdeed shall be corrected without delay; and if the king or his justiciary does not correct it, if the king be without the realm, within a reasonable time to be fixed in the charter, the aforesaid four shall bring that case to the remainder of the twenty-five barons, and these twenty-five, with the commonality of the whole realm, shall distrain and distress the king in allways that they can, to wit, by the capture of his castles, lands, possessions, and in other ways that they can, until right be done according to their will, the person of the king, the queen, and his children being saved, and when it be corrected they shall obey the lord king as before; and whoever of the land wills, shall swear that he will obey the commands of the aforesaid twenty-five barons to carry out the aforesaid, and will distress the king as much as he can with his, and the king shall publicly and freely give leave to swear to anyone who wishes to swear, and shall forbid none from swearing; but all those of his own land who of their own accord and by themselves will not swear to the twenty-five barons about distraining and distressing the king with them, the king shall cause them to swear to his command as is aforesaid. Also if any of the aforesaid twenty- five barons dies, or quits the land, or be restrained in any other way from. ‘following out the aforesaid, those who remain of the twenty-five shall elect another into his place at their discretion, who shall be sworn in the same way as the others were. In all matters which are committed to these twenty-five barons to be carried out, if by chance these twenty-five are present and disagree on any topic, or any of them when summoned will not come, or are unable to be present, that shall be had to be decided and fixed which the greater part of them has provided or ordained, just as if the whole twenty-five had agreed; and the aforecased twenty-five shall swear that they will faithfully observe all the aforesaid, and to the best of their power cause them to be observed. Besides, the king shall keep them secure by the charters of the archbishop and bishops, and Master Pandulf, that he will get nothing from our lord pope, by which any of these engagements shall be revoked or diminished, and, if he shall seek to obtain any such thing, it shall be deemed void and vain, and have no effect.9

By this verbose but carefully-worded security clause, Stephen Langton, Archbishop of Canterbury, sought to shackle King John, attempting to coerce the monarch by the threat of the military power of the rebel barons he headed; and this rebel power was to be reinforced (he planned), by oaths of fealty to the twenty-five – voluntarily given or enforced from the common people, including the freemen who were thereby to lose their freedom from baronial domination acquired by royal guarantee when enlisting in the royal militia. This absurd committee of twenty-five rebels, chosen from the ranks of the declared enemies of the king, answerable only to themselves, and self-invested with almost unlimited powers to humiliate the crown, was to decide on its own authority what constituted an offence and how severe was to be the retribution exacted. And when its members were not actively punishing the king for an alleged unproven offence, they were to pretend to be his loyal subjects for as long as this suited them. The whole security clause bespeaks the delusions of a scholar dreaming of temporal power, but totally unversed in the practical problems of formulating and enforcing legislation in times when any considerable nobleman could call upon his personal army to back him in rebellion arising from personal pique.

Dimly, through his crazy vision, Langton glimpsed the power of the pope, the feudal overlord of England. Displaying ineptitude as a practical churchman, he sought to isolate John from the protection of Innocent by requiring his bishops to join him in guaranteeing that any intervention by the supreme pontiff should be “void and vain, and have no effect.” But Pandulf was not yet the bishop of Norwich, he had not accepted the yoke of Canterbury, he remained the pope’s man, true to his master, and incorruptible by the archbishop’s blandishments. No moral course was open to Pandulf other than to report fully to Innocent on the proposed three-part pact, to be incorporated into a royal charter, whereby the church was to act as guarantor of arrangements illegally extracted from the crown by the rebels under threat of duress. And John, the possessor of the keenest administrative brain in England, was perfectly well aware of the impracticability of the security clause, and of the tremendous bargaining power it conferred upon him in his negotiations with the rebels. When the pope later set the charter aside as he was bound to annul such an affront to his overlordship – the revocation would be made by papal, not regal, authority; but the barons would remain bound in principle to any arrangement they had made of their own free will, since revocation of the agreement would not have come from them.

Once the silly security clause was known to have been incorporated into the still growing text of the Articles, John was master of the situation and could bargain from a very flexible position for the ends he sought, namely the resumption by the rebels of their oaths of allegiance after agreement had been registered, and a guarantee of the continuing social advancement of the common people, upon whom(as John had long discerned) the security of the crown was increasingly coming to rest. It is with this situation in mind, and with the benefit of hindsight, that the Articles may now be examined as the basis for the great concourse which gathered at Runnymede at John’s invitation.

The Articles begin with a section devoted to the long-debated feudal rights over heirs and widows; they progress into legal procedures and the increasing part played by the king’s court in determining disputes; guarantees to merchants and freemen are followed by financial clauses including control of taxation; and after a section relaxing John’s disciplinary hold over his adversaries, appears at last the clause that deserves to be permanently sculpted in the green field of Runnymede as the nation’s grateful, but belated, tribute to an outstanding leader and defender of his people. For it is an unprecedented and revolutionary clause, introducing a new era for the commonality of England and severely curbing the autocratic nobility which had for so long held the great bulk of the people in thrall.

This last clause to be inscribed into the Articles marks the conclusion of the pre-Runnymede phase of the bargaining; it expressed the critical concession wrested from the rebels by the king, upon receiving which John decided that the moment had come for an invitation to a formal meeting at Runnymede at which the Articles should be transcribed into a royal charter, a charter which, though itself bound to be swiftly set aside, would initiate a new basis from which the social status of his people would advance. It is a clause which establishes King John as the predecessor of Thomas Paine, as the crusader for the Rights of Man in feudal times as Paine crusaded in the same cause under the Hanoverians. It is a clause identified, to date, only by the number 48 adduced to its position on a. parchment sheet; but it merits a title commensurate with its importance. It is now suggested that it become known as the Equity Clause. Translated from the form in which it was expressed by John’s chancery, it reads:

All these customs and liberties that we have granted shall be observed in our kingdom in so far as concerns our own relations with our subjects. Let all men in our kingdom, whether clergy or laymen, observe them similarly in their relations with their own men.10

No longer was liberty to be a concession to the privileged; whatever the nobles obtained for themselves they should henceforth bestow upon their own men. Never before had so few simple words presaged such a profound advancement in the social standing of the common people of England. Notwithstanding the qualifications and vicissitudes that were yet to come, King John had lit a lamp that was to light his people out of mediaeval serfdom long before similar freedom was acquired by the commonalty of other European countries. Men like Wat Tyler would still need to throw down the gauntlet to resisting authority, and shed their blood for their cause, but the determination of authority to withstand their just demands had already been undermined by John in an undertaking that was to endure.

There was no call for John to seal the Articles, which were but the basis for a charter that was yet to be drawn up, as the security clause made clear; if the Great Seal was ever attached at the base, this was probably done in the London chancery where the seal was normally kept, and which was now under rebel control. The next act in the drama was to take place at Runnymede, where the charter was to be agreed.

The Runnymede Charter, which Blackstone with his immense authority termed merely the charter granted by King John, bears at its conclusion the date June 15, 1215, but by the practice of the times this made clear that only on this date was the great conference in session.11 It was to continue over many days, and during that time the forty-nine items of the Articles were reviewed and re-drawn as necessary by the chancery draftsmen, who expanded them into a continuous text which modern commentators have broken down into no less than sixty-three separated items. There were notable alterations, but the king’s domination of the situation is clear; there is no suggestion of the concessions being extracted to the advantage of the baronial class, the charter is designed as a grant of liberties to all free men of the kingdom and their heirs, from John and his heirs, in perpetuity. There are concessions to the disappointed rebels and their allies, the London merchants; London alone is cited as entitled to reasonable levies of taxation, the other towns which declined to follow London’s lead receiving no mention; and the general council of the realm which is to approve taxation levies is to be drawn from the major dignitaries of the realm, the lesser men from the shires no longer being summoned. But the Equity Clause is maintained, being merely re-expressed in formal legal terms. Justice for the great is to be mirrored in justice for the commonalty. John would brook no relaxation of his great principle of equal justice under the crown throughout the realm.

The security clause, no longer last but numbered 61 out of 63, was modified, for royal cognisance could not be given to the delusion that Pandulf might be called upon to obstruct communication between king and pope, since Pandulf himself has accepted (as the pope’s proxy) John’s oath of fealty to Innocent and Innocent’s successors that: “Their harm, if I know it, I will strive to remove, and do it if I can; otherwise, as soon as I can, I will communicate, or tell to such a person, as I certainly believe will tell it to them.” Instead the security clause now incorporated a general undertaking that John would not seek, directly or indirectly, to have the charter revoked. John had no need of such action, its revocation by Innocent was inevitable, and had probably already been initiated by Pandulf. But Pandulf’s name still appeared, in the following clause, this time as guarantor that John would take no punitive action against the rebels for their actions between Easter and the restoration of peace; there would have been nothing for Pandulf to do had peace been restored, for John was ever generous to rebels who recanted and resumed feudal allegiance to him as their king.12

But there was to be no peace, only a temporary lull in the conflict, even though John sealed the Runnymede Charter, probably with the Privy Seal he carried with him into the shires, for the tapes that remain attached to the original charter are not long enough to accept his Great Seal, and the mass of the fire-melted wax suggests that it was only large enough to accept the impression of a much smaller seal.

Any belief that, at Runnymede, John was coerced by the great rebel army into making peace on their terms, fades as the facts of the situation emerge from the false legend. Modern scholars, even those still bemused by the prejudice that John was an evil king, now concede that before the end of the conference they had begun to slink away. Disgusted by their lack of success against the seemingly-defenceless king, they sulkily refused to re-take their oaths of fealty to him. An alarmed Langton now saw his dream of power dissolving as the prospect of renewed unity faded, for he could not hope to exercise power from the king’s shadow, through the committee of twenty-five (now nominated as twenty four rebels and the Mayor of London), if that committee did not conform to his basic concept of being the king’s men except when adjudicating against him.

In a desperate attempt to revive his dream of power, Langton called upon the rebels to resume fealty to the king; it was to be one of his last acts as John’s archbishop, and it was ineffective. Instead of gathering again into a composite group under the king, easily influenced by the archbishop from his as one of the greatest dignitaries of the realm, the rebels stood aside and watched as Langton was himself deprived of his position, and with it his capacity to fish in troubled waters. Innocent moved strongly against the rebels, and when Langton failed to comply with the papal directive he was suspended by Pandulf, notwithstanding that the archbishop was on the point of setting out for Rome. He was never to return during John’s reign.

A number of copies of the Runnymede Charter were distributed, but if they had any effect it was to confirm that John remained in control; no action followed in the shires, probably because the authorising counter-signs had not been sent out with the charter. On June 27, John went so far as to decree the seizure of the lands of any who declined to swear allegiance to the twenty-five; he could have issued a hundred such decrees without any action being taken in the absence of the counter-signs. But John, in his capacity as king, made great concessions to the rebels, even seriously weakening his own military position in the process, in an endeavour to draw them back to his side. It was in vain, the twenty-five members of the committee were now absorbed in formulating demands against the king, each for himself, and none for the realm. The outcome was inevitable. In the face of continuing rebel obstinacy and selfishness, John re-grouped his military forces, and the civil war he had striven to avoid came to pass. The rebels remained based on London; the king held all the major fortresses, including Dover Castle, where, as he now lacked the facilities of the London chancery, he seems to have deposited the sealed Runnymede Charter.

John’s military successes against the rebels soon demonstrated that he could have crushed their revolt with ease, had he not been minded to seek their return to his standard through negotiation. But soon an ugly new development complicated the situation; Phillip Augustus had devised a means of circumventing the papal guarantee to John as a crusader! An absurd claim was made that John was not the rightful king of England, and a pretender was put forward – Phillip’s son, Prince Louis. The pretender’s claim deceived no-one, but it was not put forward as a serious claim, only as a pretext, and it served to excuse Prince Louis’ landing in England at the head of a French army, to be welcomed by the rebels into London, where, according to French sources, he was crowned king, and where he took over the trappings of kingship which remained in John’s capital.

The military situation was to be complicated by the sudden death of John, a death which (typically) was to be misrepresented by his detractors as due to gluttony. But this darkest hour was to prove the fore-runner of the dawn. The general nobility was deeply shocked by the consequences to the nation which had stoned from the revolt of a minority of their number; they closed ranks around the person of John’s heir, the nine-year old Prince Henry, who was taken into the care of William Marshal, Earl of Pembroke, and the greatest noble in the land, and hurriedly crowned him as Henry III at Winchester; a simple gold ring was employed for this ceremony in place of the Crown of State. Erstwhile rebels now joined forces with the earl, and helped him win a decisive victory over Louis at Lincoln. At the ensuing Treaty of Lambeth Louis abandoned his false claim to the English throne, and undertook to return the belongings of the king to which he had helped himself. The Great Seal of King John was not amongst the items returned, it may already have been destroyed, or perhaps Louis tucked it away as a souvenir of his short-lived spurious occupancy of the throne of England.

In accordance with the tradition of the preceding centuries, the accession of Henry III was marked by the issuing of a promise of good government, but the boy king can have played little part in its formulation. Under his father, the great King John, good government had become a vastly expanded term, too wide-ranging (as the great nobles now seem to have decided) to be expressed in a single charter. And so the two charters were issued, the smaller, the Charter of the Forest, hived off forest matters, the larger charter, which by virtue of its greater size was called the Great Charter, or in the official legal latin, MAGNA CARTA, listed the remainder. That Magna Carta, which first was granted during the reign of Henry III, has been misrepresented by historians, is a major distortion of historical fact.

Of course, as Magna Carta is properly located in the succession of charters of liberties, it bears resemblances to the Runnymede Charter and also to the Charter of Henry I, but it also displays major differences, including the exclusion of the absurdities which mark out the Runnymede Charter as originating in ecclesiastic dementia, for the security clause disappeared for ever, as did the limitation of the support the king could call upon from the nobles, both military and financial. But the Equity Clause survived, and was incorporated unchanged into both charters; however, the tragic lifting of the strong hand of John had unfortunate consequences for the common people of England, for the Equity Clause was now qualified by a new clause which conflicted with its spirit, and which reserved to ‘archbishops, bishops, abbots, priors, templers, hospitallers, earls, barons, and all others persons as well ecclesiastical as secular, all the franchises and free customs they previously had.’

Thus Magna Carta, when it eventually appeared at the outset of the reign of Henry III, far from initiating a great advance in the freedom of Englishmen, actually gravely retarded the great forward surge of human rights initiated by King John and incorporated by him into the Runnymede Charter in 1215. But the principles of human rights could no more be permanently expressed in one or two royal charters in the 13th century than they can be in the 20th. The revising of Magna Carta was to be a continuing process as English constitutional law developed. It was the revision of Magna Carta in 1225, when Henry reached his majority, that was to be placed on the statute book and become the bedrock on which the liberty of Englishmen was to rest. And still the Equity Clause of King John endured, and the passage of centuries merely brought an ever-increasing appreciation of its importance; thus Sir Edward Coke, the great legal commentator of the 17th. century was loud in his praise of John’s great gift to the common people of England, lauding the Equity Clause, he wrote:

This is the chief felicity of a kingdom, when good laws are reciprocally of prince and people (as is here undertaken) duly observed.13

But the day has yet to dawn when this enlightened view sheds credit upon the author of the clause, King John, one of the greatest kings ever to occupy the throne of England, and perhaps one of the most concerned to advance the cause of his people against the oppressions of his day.

The Treaty of Lambeth, by establishing peace in England, satisfied the final condition Innocent had set as requisite before Langton could be freed from restraint in Rome. The archbishop returned to England, and resumed his position at Canterbury, but he was never to attain the secular eminence achieved by his predecessor, Hubert Walter, or wield the temporal power Walter had enjoyed, and after which Langton lusted. Power, during the minority of Henry III, lay first with the Earl of Pembroke, and after Pembroke’s decease with Pandulf. To assuage his bitter continuing hate for John, the king who had exposed and humiliated him. Langton resorted to a cowardly vendetta mean enough to satisfy his twisted mind. As Thomas Paine, after his death, was to be assailed by a scurrilous biographer, so the ecclesiastic annalists were primed to prepare scurrilous accounts of the deceased King John, and to accompany the denigration of John with the lauding of Langton.

The myth of the evil King John was deliberately created, but it was not yet the myth of Magna Carta, for Coke and Blackstone recognised, studied and wrote of the true Magna Carta, the charter granted by Henry III, in their commentaries. But the myth of King John was to provide a ready-made basis for the myth of Magna Carta when it was deemed expedient for this to be propagated during the 18th century by the defenders of privilege who stood in direct line with those ‘archbishops, bishops….. etc., who had degraded the Equity Clause of King John by introducing into Magna Carta the conflicting clause which preserved their privileges to the detriment of the free-men of England.

The arch-defender of privilege in the 18th. century was Edmund Burke, and there are strong similarities between the careers of Langton and Burke. Both exercised their facility to misrepresent historical fact in a period when a great opportunity had arisen for the advancement of the commonalty, and each threw his weight behind the faction concerned to retain effective power in the hands of the privileged.

Both Langton and Burke succeeded in their defamatory campaigns, which were not only believed at the time they were launched but were given credence in later centuries. For far too long have the names of the great reformers, King John and Thomas Paine, been besmirched by malicious slander. It is perhaps fitting that as the light of truth strengthens they should share an opportunity to have their later places in history re-appraised, just as they have shared the ignominy or character-assassination.

The first published re-appraisal of the fanciful popular presentation of John’s charter seems to have appeared in November 1904 when Edward Jenks published in The Independent Review his challenging paper, “The Myth of Magna Carta.” Jenks’ paper was noticed by W.S. McKechnie in his book, Magna Carta (1905), and it has remained in the bibliography of John’s charter, but it has never been accorded its proper importance, possibly because Jenks did not follow it with a detailed analysis of the myth he exposed and debunked. Thus even G.M.Trevelyan, who in his History of England made comments which underlined the part played by 18th. century politicians in the creation of the myth, nevertheless accepted the myth, although his history appeared more than twenty years after Jenks’ paper.

Jenks was a lawyer, rather than a historian, and it was as a man of law that he had long accepted and taught the prevailing view that Runnymede witnessed the culmination of a popular revolt against the king, spearheaded by the barons, which laid the basis of civil liberty for all degrees of Englishmen. But when Jenks ha reason to look carefully at John’s charter, he was appalled to discover that it had done nothing of the sort, it being mainly the outcome of selfish action h barons to promote their own interests; and he found the Runnymede charter had proved a stumbling block in the path of progress.’

Jenks laid the blame for the unquestioning general acceptance of the myth at the door of Dr. William Stubbs, doyen of English constitutional historians, whose monumental work became the standard work of reference when it was published in 1873- 8, and Jenks began his paper with the quotations from Stubbs which head the present paper also. Jenks speculated briefly on the reason why Stubbs had been led into error, and thought that Sir Edward Coke, whose celebrated Second Institute had appeared in 1642, was the culprit. But here Jenks fell into another long-persisting error, that of confusing John’s charter with the Great Charter of Henry III:

As J.C. Holt has declared in his scholarly study, ‘In the 17th.century, Coke never used the charter of 1215. His commentary was based on the re-issue of 1225. He only seems to have known of the 1215 charter from the chronicle of Matthew Paris.’14

The crucial part played in the unveiling of the relevant historical documents by Blackstone’s publication of 1759 strongly suggests that the origin of the myth should be sought after that date. But the decades following 1759 did not blend into a placid period facilitating re-thinking by influential opinion of the lessons of Runnymede. On the contrary, those decades witnessed the domination of the domestic scene by a series of overseas events of shattering impact. In 1759 the British people leapt for joy, but not in their reception of Blackstone’s revelations, of which the great mass of Britons have always remained in total ignorance; public jubilation in 1759 was centred on the thrilling ascent of the Heights of Abraham by the forces of General Wolfe to overwhelm the French army and capture Quebec. In 1762 France conceded all her territory in Canada to Britain, but the political climate on the western shore of the Atlantic, which might then have been expected to grow calmer, instead grew tense as the British government sought to ease the burden on the British people, the most heavily taxed in Europe, by imposing tax levies on the American colonies. Friction between the colonists and the Home government escalated through acts of reprisal, such as the Boston Tea Party, into bloodshed. In 1776, shortly after the publi- cation of Paine’s sensational pamphlet, Common Sense, the dispute was brought to open conflict by the American Declaration of Independence. During those seventeen years it would have taken greater political courage than was possessed by the public figures of the day to warn the British nation in clear terms of the close parallel between the path to revolt, along which an increasing number of resenting Americans were being driven, and the progression to Runnymede of the rebel barons protesting against John’s last imposition of scutage. At least one Member of Parliament did see this parallel, but he carefully stopped short of spelling out the obvious dangers and possible consequences of contemporary goverment policy. In 1775, in a speech to parliament on American affairs, Ednund Burke remarked:

Abstract liberty, like other mere abstractions, is not to be found.Liberty inhere in some sensible object; and every nation has formed to itself some favourite point which, by way of eminence, becomes the criterion of its happiness. It has happened, you know, Sir, that the great contests for freedom in this country were from the earliest times chiefly upon the question of taxing.

That Burke was a notable contemporary of Paine, at one time a personal friend and later an uncompromising enemy, is common knowledge. But although Burke has attracted great interest as a political commentator, Burke the man has been studied less than might be expected, and his most authoritative modern biographer, Professor C.B. Cone has pointed out that his voluminous papers did not become available to the public until the surprisingly late date of 1949. Burke’s address to parliament on American affairs has naturally endeared him to American opinion, and his advocacy of the American cause in the face of the accepted imperial right of the home country to control the colonies at first seems to mark him out as a statesman more courageous and far-sighted than most of his fellows. But at the time he made his speech, his advocacy was rendered less effective in parliament by a circumstance then well known but now rarely mentioned; in December 1770 the New York Assembly had unanimously elected Burke its agent in London, thus effectively making him an ambassador to Britain charged to represent American interest, and he retained this post until it was liquidated by the outbreak of the war. For his part-time services as agent Burke received a salary of £500 a year, ten times the amount received by Paine for his full-time service as an Excise Officer, a criterion which sets the modern equivalent of Burke’s stipend at about £70,000;15 and in addition Burke received expenses, which in 1774 had amounted to 140. On second thoughts, therefore, it becomes surprising that Burke did not give better value to his American sponsors by advocating their cause with greater vigour. This surprise becomes greater when it is appreciated that Burke was already the author of an outline of English history up to the reign of King John, that he was a skilled latinist who quoted at length from authors of antiquity, and that he was a student and historian of English statutes which in early times were written in the latin language. No other Member of Parliament was better qualified than Burke to understand the implications of Blackstone’s publication and to warn parliament of the likelihood of history repeating itself.

The American War of Independence was formally concluded in 1783 by the Treaty. of Paris which recognised the United States of America internationally, but hardly had the British people settled down to the new situation when another and even greater conflagration brought the groundswell of popular rebellion swirling close to the southern shore of England. In 1789 the greatest economic crisis of the century in France, attended by widespread shortage of food and consequent rioting, erupted in the French Revolution, which swept away the French aristocracy. And now Edmund Burke, who in his twin capacity of paid agent of the New York Assembly and Member of Parliament had displayed professional sympathy with the American resentment of autocratic government, recoiled in horror from the French activists who looked to the American precedent.

Initially there was much sympathy in England for the French rebels, and for a while Burke remained silent; but as the exuberant Frenchmen set themselves up as the originators of a new European order, which could easily cross the Channel, Burke projected himself to a new prominence as the spokesman for anti-revolution reaction by publishing his Reflections on the French Revolution, to which Paine replied with his immensely-popular first part of Rights of Man, which set ablaze. the emergent reformatory enthusiasm of working-class opinion. It is in the ensuing period of bitter ideological dispute, waged between the supporters of privilege broadly following the standard raised by Burke, and the more numerous but less articulate aspirants towards a more equitable society who hailed Paine as their spokesman, that we can now discern the origin of the myth of a nation-wide popular rebellion, headed by the barons extracting justice from a tyrannical King John.

The Burke-Paine controversy has come to be accepted as a classic illumination of the crisis of public conscience in England during the initial stages of the French Revolution, but this controversy is usually considered only in the context of the first round, which comprised the publication of Burke’s pamphlet and Paine’s reply, and the reception accorded them. The present paper will extend consideration of this controversy to its less discussed second round; but it may first be commented that even the first round, extensively debated though it has been, has not been accorded a generally-agreed assessment. Continuation of disagreement is probably inevitable, since the attitudes of the two chief disputants and their political heirs appear irreconcilable. At the time they clashed, Liberty was a word on every man’s lips, but with varying connotations; to some, the French Revolution represented the greatest advance in history towards civic justice for the common man, but others saw it as a victory for tyranny. Burke still has supporters, but Michael Foot has recently written:

‘Government is for the living, not for the dead, had been Paine’s reply to Burke in 1791; forty years later, England marched on, in company with France and America, along the road which Paine, not Burke, had mapped out for her.16

One man who seems to have accepted that on the limited showing of the first round Paine had proved to be the more successful disputant, was. Burke himself, who made no attempt to continue the controversy by open debate, and in parliament, as well as in popular opinion, Burke was worsted, for as he has himself recorded, the Morning Chronicle of May 12, 1791, carried the following notice of the impending cessation of Burke’s parliamentary career:

The great and firm body of the Whigs of England, true to their principles, have decided on the dispute between Mr.Fox and Mr. Burke; and the former is declared to have maintained the pure doctrines by which they are bound together, and upon which they have invariably acted. The consequence is that Mr.Burke retires from Parliament.17

This newspaper report, as Burke wryly pointed out, was premature; Burke was not yet extinguished as the chief apologist for entrenched privilege, within parliament or without, but he had been compelled to review his strategy and revise his campaign in its defence.

The consequent change in tactics by the Burke faction was swiftly scented by the sensitive political nose of Thomas Paine, and he was quick to combat this new challenge, meeting it on its own ground, as was his practice. He did so in a long footnote appended to the second part of his Rights of Man, and began it with a reference to the contemporary circumstances which necessitated it:

Several of the Court newspapers have of late made frequent mention of Wat Tyler. That his memory should be traduced by Court sycophants and all those who live on the spoil of a public is not to be wondered at. He was, however, the means of checking the rage and injustice of taxation in his time, and the Nation owed much to his valour.18

Paine’s words, published in 1792, evince a campaign intended to denigrate popular leaders emerging like Wat Tyler, and by implication like the French revolutionaries, from the broad mass of the people; and they show that this campaign was being carried on, not by a pamphlet such as Burke’s Reflections to which Paine had made his immensely successful reply, but by a series of co-ordinated derogatory references calculated to influence informed opinion without providing a platform from which Paine could launch a second devastating counter-attack. Paine did reply, and in the permanent form of this footnote to one of his best known works, which continued by setting out the view then generally held of the incident which rocketed Tyler to the leadership of the Kentish below in 1381 (this was an indecent approach by a collector of poll tax to Tyler’s daughter under pretext of verifying whether she had reached the qualifying age of fifteen years, which provoked a violent reaction from her enraged father, resulting in the death of the revenue officer). But it was his conclusion to the footnote in which Paine fitted together the pieces of the contemporary jig-saw:

All (Tyler’s proposals) were on a more just and public ground than those which had been made to John by the Barons, and notwithstanding the syncophancy of historians and men like Mr. Burke who seek to gloss over a base action by the Court by traducing Tyler, his fame will outlive their falsehood. If the Barons merited a monument to be erected in Runnymede, Tyler merits one in Smithfield.18

To identify and collate the ‘frequent mention of Wat Tyler’ in court newspapers, to which Paine referred, would involve arduous research, and might produce little substance in view of the oblique nature of the campaign; Paine seems to have been of this general view since he did not identify any particular comment. Newspaper research may eventually fill in a few details, but the general tenor of Paine’s opening to his footnote is already well substantiated by authoritative comment, as will appear below, and it is more conducive to the present thesis to concentrate on Burke’s second pamphlet in defence of privilege which has long been available in his published writings. Although referred to much less frequently than his Reflections, this second essay was in fact a continuation of his first pamphlet, as becomes apparent when the shortened title by which it is usually identified is expanded to its original length: An Appeal from the New to the Old Whigs, in Consequence of some late Discussions in Parliament, relative to the Reflections on the French Revolution.

Burke’s Appeal is a lengthy document, nearly half the length of his Reflections, and written in a curious style which appears to have had the object of restricting its circulation to the well-schooled; ‘Mr. Burke, is frequently spoken of in the third person, but the first person is also frequently employed, thus conveying the general impression that it was written by one of Burke’s supporters; and it is laced with quotations in Latin and Greek, which are not translated, and hence obscure his line of argument, and make critical appraisement extremely difficult for general readers. The author is not identified, but Professor Cone opinions that Burke’s authorship would have been clear to the readers to whom the Appeal was directed.19 It is not surprising, in these circumstances, that Burke’s Appeal has not hitherto been greatly studied by general readers as a commentary on the practical politics of his faction.

Little of the first part of the Appeal bears upon the present theme; mid-way Burke complains that the new Whiggism has been imported from France, and significantly remarks on the growing use of the term the people; and it is only in its last third that Burke develops his new manoeuvre. Here he inserts quotations from Paine without acknowledging them, and pointedly comments that Paine’s opinions call for no refutation other than that of criminal justice an indirect admission, perhaps, that he was privy to the anti-Paine measures to be undertaken by the establishment. And at last Burke comes to the nub of the matter, the meaning to be applied to the term so prominently employed in the contemporary dispute, the PEOPLE.