By Dr. Sean Cronin – Lecturer at the New School for Social Science, New York and Washington correspondent for the Irish Times, Dublin. He is also a Vice-President and editor of the Thomas Paine Society.

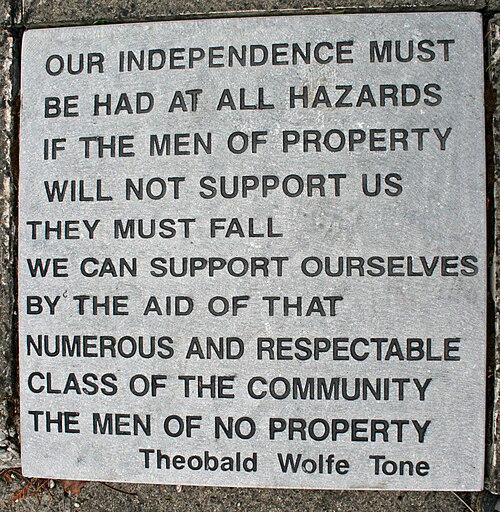

THOMAS PAINE PLANNED to visit Ireland in the summer of 1791 because it was a country ripe for revolution. Other matters intervened. Among the educated he was a household name. His Rights of Man was “the Koran” of Belfast, Theobald Wolfe Tone learned in October 1791 when he went north from Dublin to found the first Society of United Irishmen. Edmund Burke, an Irishman, lost the loyalty of his radical countrymen to Paine because of his defence of the status quo. Public opinion in Ireland, Catholic as well as Protestant, leaned to Paine. The original United Irishmen, the Presbyterian merchants and manufacturers of Belfast, saw Paine as a hero and Burke as a villain. When Tone wrote his “Argument on Behalf of the Catholics of Ireland”, to convince them that they had nothing to fear by supporting full rights for Catholics and allying themselves with the majority in an independent Ireland, with its own national government, he clinched his case with the remark, “for, after Paine, who will, or who need, be heard on that subject?”

Of the 40 to 50 thousand copies of Rights of Man sold in England, Scotland and Ireland, more than 20,000 were circulated in Dublin, which was one of the reasons why Paine wanted to visit Ireland. Tone claims that the Rights of Man, combined with the French Revolution which it explained, “changed in an instant the politics of Ireland.” This change led to the founding of the United Irishmen in Belfast, and a few weeks later in Dublin, the most radical movement in Irish history, one that has had a lasting influence on the politics of the Irish people.

Paine supported the United Irishmen’s revolutionary republicanism, knew some of its leaders, including Tone and Lord Edward Fitzgerald, the egalitarian aristocrat chosen to lead the 1798 rebellion, and befriended James Napper Tandy, a Dublin democrat and fellow exile in Paris. Tandy, a somewhat boastful man, believed that his name would spark rebellion in Ireland. He is remembered in the ballad, “The Wearing of the Green.” He and Paine could be found in the Irish Coffee House, a Paris meeting place for Irish revolutionaries, often in the company of Thomas Muir, the Scots radical who was tried for sedition because he had told someone to read Rights of Man. All three talked treason against the Crown, the Pitt government was told by its many secret agents.

Tone wrote in his diary on March 3, 1798: “I have been laterly introduced to the famous Thomas Paine and like him very well. He is vain beyond all belief, but he has reason to be vain and, for my part, I forgive him. He has done wonders for the cause of liberty both in America and Europe, and I believe him to be conscientiously an honest man. He converses extremely well and I find him wittier in discourse than in his writings, where his humour is clumsy enough. He read me some passages from a reply to the Bishop of Llandaff, which he is preparing for the press, in which he belabors the prelate without mercy. He seems to plume himself more on his theology than his politics, in which I do not agree with him. I mentioned to him that I had known Burke in England and spoke of the shattered state of his mind in consequence of the death of his only son Richard. Paine immediately said it the Rights of Man which had broke his heart and that the death of his gave him occasion to develop the chagrin which had preyed upon him since the appearance of that work. I am sure the Rights of Man has tormented Burke exceedingly, but I have seen myself the workings of a father’s grief on his spirit and I could not be deceived; Paine has no children…He drinks like a fish, a misfortune which I have known to befall other celebrated patriots. I am told that the true time to see him to advantage is about ten at night, with a bottle of brandy and water before him, which I can very well conceive”

Tone disliked The Age of Reason, calling it “damned trash.” He did not object to it on religious grounds of Anglican stock, he was likely a freethinker but thought Paine must be doting to switch from politics to theology; yet he remained an admirer of Paine.

In the summer of 1798, rebellion broke out in Ireland. Tone tried to organise a French expedition to aid the United Irishmen. An expedition under General Hoche at Christmas 1796 had reached Bantry Bay but was forced by the winds to turn back. Tone was aboard. Paine worked with Tandy to help the rebels. He sent a memorial to the Directory for a thousand men and five thousand. In August 1798 General Humbert sailed for Killiala in County Mayo with a thousand men. The Irish flocked to his flag. He defeated General Lake at “the races of Castlebar,” and broke through to the heart of the country, only to be surrounded a couple of weeks later by Lord Cornwallis at Ballinamuck. Humbert surrendered, his Irish allies were executed.

Shortly after Humbert sailed, Tandy set out for Ireland on a fast ship, the Anacroon, landing on the Donegal coast north of Mayo. He learned that Humbert was a prisoner, the rebellion defeated. He scattered a few proclamations, then sailed back to the continent via the Orkneys and Norway with the British hot pursuit. Tandy eventually reached Hamburg and asked for asylum. He held the rank of Major General in the French Army, but despite this was handed over to the English in October 1799. Tried, convicted and sentenced to death, he was reprieved after Napoleon, then First Consul, threatened reprisals, and was ordered transported beyond the seas. And then he was permitted to return to France a free man. Up to now the reason for this has been a mystery. The explanation, it turns out, was Paine.

Robert Livingstone, Secretary of Foreign Affairs under the Continental Congress, was Thomas Jefferson’s Minister to France. Paine’s letter to Livingston for Tandy came to light in the summer of 1979 when Paul O’Dwyer, former President of New York City Council, a great admirer of Paine, found it among Livingston’s papers. The letter, dated “25 Brumaire Year 10,” reminded Livingston of an incident during the American Revolution in which both were involved. An English officer, Captain Charles Asgill, was sentenced to death by the Americans as a reprisal. The French court was shocked, especially the Queen. Livingston enlisted Paine’s polemical skills, first to explain the matter publicly, secondly to have Asgill reprieved. Paine blamed the English for Asgill’s plight, then wrote to Washington a plea for Asgill’s life. Congress lifted the death sentence and everyone’s honour was upheld.

Paine’s letter for Tandy opens with the salutation, “Dear Friend, “and went on to explain the reason for writing, “to engage your benevolence, and, as far as you can give it, your assistance in behalf of an honest unfortunate old man whom you know by name, Napper Tandy, who after several years of imprisonment is now sentenced to Botany Bay.

“You remember that at the time of Asgill’s Affair you were Minister for Foreign Affairs, and you will recollect a conversation you had with me respecting Asgill, in consequence of which I published a piece upon the subject and wrote to General Washington to engage him to suspend the execution of the sentence upon Asgill.

“During that suspension the letter of Vergennis (sic) arrived asking in the name of his Court (or rather that of the Queen) a remittance of the sentence, which terminates the affair, and relieved us all from a painful sensation.

“Now as you were an instrument for saving Asgill, I think you might find aid to way, without involving your diplomatic character, to throw in your relieve poor Napper Tandy. What I wish to be done for him is to let him tran- sport himself, in which case I suppose he will go to America, because that our Government is reformed, the honest and the unfortunate will find Asylum there.

“Neither Talyrand (sic), nor any person in the government here, knows anyt- hing of the case of Asgill, and I think you might very consistently write private note to Talleyrand to inform him of it, and to engage him to make government acquainted with it, and to ask in return a remittance of the sent- ence of Napper Tandy, for though it is not now the same government, it is the same nation.

“Cornwallis, you know, was in America while the affair of Asgill was perding, and I cannot see any impropriety (keeping the Ministerial character out of the question) in your writing a note to remind Cornwallis of the circumstance and to hint to him your wish that he would be as friendly to Tandy as you had been to Asgill.

“So far from there being any inconvenience in this, I think the contrary will be the case. It will most probably happen that you and Cornwallis will meet either in company or at a public audience, and this preliminary introduction will take off the awkwardness which might otherwise take place at a first meeting, and furnish a subject of conversation when it might be cult to start a political one and hypocritical to propose a friendly Nothing brings people more easily together than a joint endeavour to do a good thing.

“If you are much engaged and have not leisure to turn the whole of affair in your mind I will throw a few thoughts together for the purpose forwarding it; and if, while I stay here I can render you any auxiliary aid, you know there is nobody more disposed to do it than myself – In remembrance of former times and former friendships, I remain

Your fellow-labourer

Thomas Paine.”

Cornwallis was Viceroy and Commander-in-Chief of the forces in Ireland during and after the rebellion of 1798 and the Act of Union with Great Britain thirty months later. He acted on Paine’s request, though how he received it we do not know. Tandy went to France and died shortly afterwards. Even at the end of his eventful life he still dabbled in conspiracy and was loosely involved in Robert Emmet’s plans for a rising in July 1803. Emmet was hanged.

Robert Emmet’s brother, Thomas Addis Emmet, a founder of the United Irishmen, went into exile in America after the Peace of Amiens, March 1802, and became Attorney General of New York. He was a friend of Paine during the lonely final years. He was Paine’s executor and was named in his will. There is a statue to Thomas Addis Emmet in St. Paul’s churchyard, Lower Broadway, New York City.

Wolfe Tone, like Tandy, set out from France for Ireland in the autumn of 1798 to join the revolution and after a sea battle was captured by the English. Tried by court martial in Dublin, he was sentenced to death by hanging in November 1798. He committed suicide in prison, although some Irish mintain he was murdered. He had asked to be shot because he was an officer in the French army, but they refused his request. “In a cause like this,” he said, “success is everything Washington succeeded and Kosciusco failed.” He was prepared for the sentence of the court and would discharge his duty, he added: This cryptic remark may well explain his death. Paine’s Rights of Man explains his life.