By Harry H. Pearce – President of the Secular Society of Victoria, Australia

This paper was given as Pearce’s Presidential Address to the Society on July 17, 1979.

THERE IS NOT only a problem, but many, about Paine’s early life before he went to America, when 37 years old, a mature man. Yet Moncure Conway, the recognised standard biographer of Paine, in a work of nearly 500 pages devoted only 31 to Paine’s formative years in England. This can largely be due to the following circumstances that he details in his Life of Paine:

“In 1802 an English friend of Paine, Redman Yorke, visited him in Paris. In a letter written at the time, Yorke states that Paine had for some time been preparing memoirs of his own life, and his correspondence, and showed him two volumes of the same. In a letter of January 25, 1805, to Jefferson, Paine speaks of his wish to publish his works, which will make, with his manuscripts, five octavo volumes of four hundred pages each. Besides which he means to publish a miscellaneous volume of correspondence, essays and some pieces of poetry.’ He had also, he says, prepared historical prefaces, stating the circumstances under which each work was written. All of which confirms Yorke’s statement and shows that Paine had prepared at least two volumes of autobiographical matter and correspondence. Paine never carried out the design mentioned to Jefferson, and the manuscripts passed by bequest to Madam Bonneville. This lady, after Paine’s death, published a fragment of Paine’s third part of The Age of Reason, but it was afterwards found that she had erased passages that might offend the orthodox (My emphasis – H.H.P). Madam Bonneville returned to her husband in Paris, and the French Biographical Dictionary states that in 1829 she, as the depositary of Paine’s papers, began ‘editing’ his life. This, which could only have been the autobiography (my emphasis – H.H.P.) was never published. She had become a Roman Catholic (same – H.H.P.). On returning to America in 1833, where her son, General Bonneville (also a Catholic), was in military service, she had personal as well as religious reasons for suppressing the memoirs. She might naturally have feared the revival of an old scandal concerning her relations with Paine. The same motives may have prevented her son from publishing Paine’s memoirs and manuscripts (same H.H.P.). Madam Bonneville died at the house of the General in St. Louis. I have a note from his widow, Mrs. Bonneville, in which she says: ‘The papers you speak of regarding Thomas Paine are all destroyed, at least all which the General had in his possession. On his leaving St. Louis for indefinite time all his effects – a handsome library and valuable papers included – were stored away, and during his absence the storehouse burned down, and all that the General stored away were burned.’

“There can be little doubt that among those papers burned St.Louis were the two volumes of Paine’s autobiography and correspondence seen by Redman Yorke in 1802. Even a slight acquaintance with Paine’s career would enable one to recognise this as a catastrophy…” (Conway, x-xi).

A similar catastrophe occurred to Lord Byron and Sir Richard Burton and our own Bernard O’Dowd. Is it any wonder that a modern writer says that, “considerable mystery surrounds (Paine) and his career. One can begin with the paradox of Common Sense….written by a man with only the briefest experience in this country (America). Until now historians have failed to explain either the unique impact or the roots of the ideas expressed by Paine.” (Foner, Eric. Tom Paine and Revolutionary America. Oxford University Press, 1976. p.xii.)

THE ROOTS OF THE IDEAS EXPRESSED BY PAINE:

The same author says, “The problem of Common Sense, however, is only one facet of the larger problem….Biographers have always faced an unenviable task, and not only because of the complexity of Paine’s personality and the fact that most of his correspondence and papers…were accidently burned over a century ago. To depict Paine in his entirety requires a knowledge of the History of America, England and France in the Age of Revolution and familiarity with Eighteenth century science, theology, political philosophy and radical movements. Paine’s connections must be traced among the powerful in Europe and America, and also in the tavern-center world of political artisans in London and Philadelphia. The questions central to an understanding of Paine’s career, in fact, do not lend themselves to exploration with the confines of conventional biography” (p.xii).

“We can only speculate about Paine’s contact with the coterie of nonconformist artisans, clergymen, and intellectuals who made up Franklin’s ‘Club of Honest Whigs’ in London… Among the members who seem to have influenced Paine were three writers: James Burgh, a London schoolmaster, Richard Price, a dissenting minister and teacher, and Joseph Priestly, a dissenting clergyman and scientific and political experimenter.” (Ibid. p.7.)

We are told that Lewes was “a center of political disaffection,” and that Wilkes at one stage visited The Wilkes movement, played an important role in engaging the political energies and broadening the political education of the artisans, shopkeepers and humbler professional men among whom Paine moved. (Ibid. p.11.)

So it is with this man, so well known of, but so inadequately known or the makings of him are, that I wish to give some account of in so far I have been able to gather from the biographies of Paine that I have, and think that half the trouble is due to the historic religious hatred, lies, sla- nder and libel by Christian apologists that has helped to prevent the preservation of documentary and oral records that escaped destruction in the fire mentioned. Christians did all they could by all means they had to wipe every vestige of anything favourable to the memory of Paine. To advise anyone even to read Paine was a treasonable offence, and even to mention his name was enough to be thought treasonable (Thomas Muir had among the charges laid against him one that asserted that he had advised a person to read Paine).

Paine burst out upon the world with his Common Sense in support of the American colonists after he went to the colonies in 1774. But what was his English background that gave him the astounding ability to write that pamphlet and have it published by January 1776? He was just forty years old.

Despite the importance and influence of Paine on America and England there is no in-depth study of his first thirty-nine years. Even Moncure Conway has only 31 pages devoted to this period. It is about time the situation was rectified. I have half-a-dozen Lives of Paine, the authors of which also skip over his early years in a similar manner, with only passing reference to the most significant events without examining the vital implications they could, or did, have in forming Paine’s ideas. At 39 years of age it must be obvious that he would have formed very definite and mature opinions to have been able to write Common Sense so soon after landing in America.

So I can only take what has already been published as I have no means in Australia of making original research. But in this paper I hope to set the pattern for someone to follow-up. In doing so I can only take what seem to me to be the most significant events in Paine’s early life. A lot of other things I must pass over.

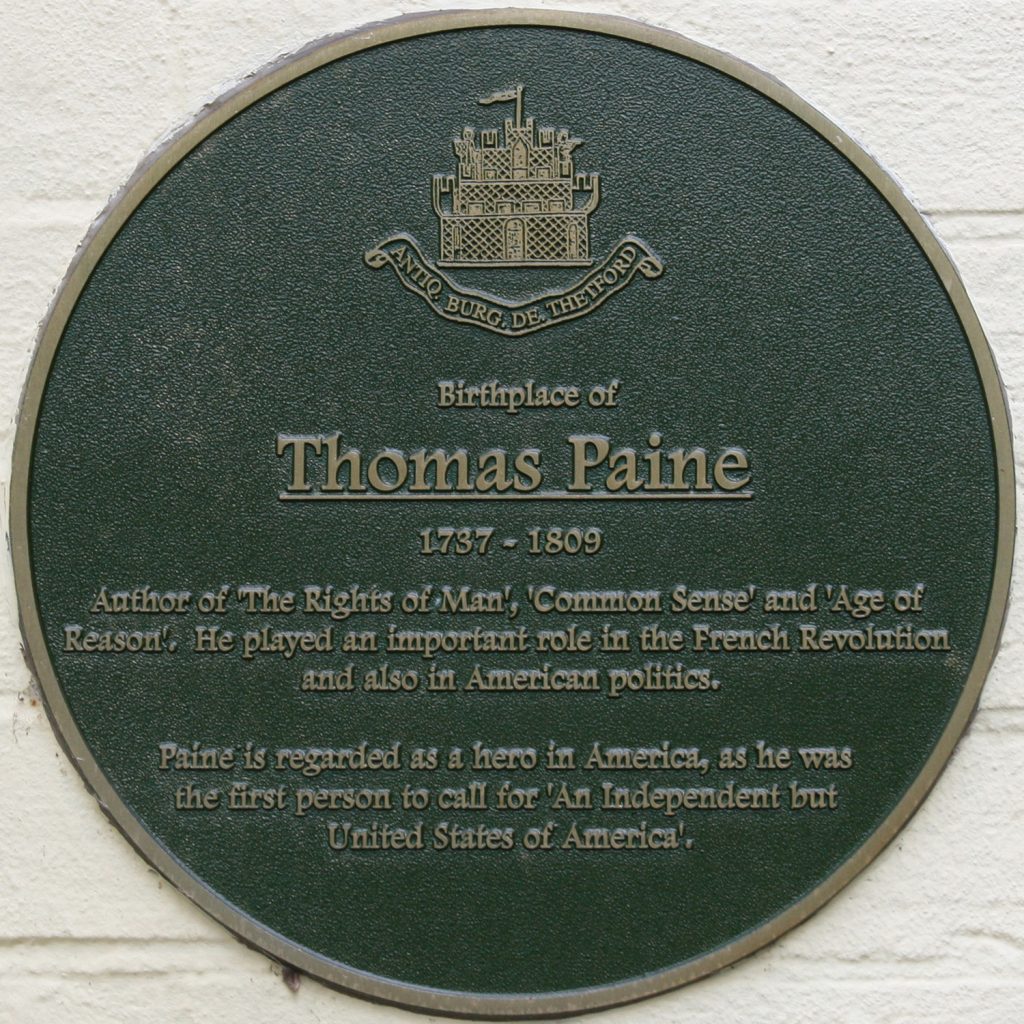

Paine was born in Thetford, Norfolk, 29th January, 1737, of Quaker/Anglican parentage, and went to the Thetford Grammar School, which he left at years of age. Now, here is the first significant thing, the implications of which have been completely missed. This school was not an ordinary one depending on parish support, as its name “Grammar” school should indicate. It was founded in 1566 on a legacy left by a Sir Richard Fulmerston, and did not depend on public funds, and taught such things as history and the sciences, which would, almost for certain be along the lines of what would then called Natural Philosophy, which is now divided up into the various branches of study such as astronomy, physics, chemistry, etc., including mathematics. (Woodward, W.E. Tom Paine: America’s Godfather, 1737-1809. Secker & Warburg, 1946. p.34.)

Knowing, as we do, the interest that Paine took in these things, here have at the very outset of his life, a form of education that has not followed up. I need only just mention at this point his interest in designing iron bridges. With the teaching of “history,” whatever its nature have been, the implications of it we might validly suggest, could have set Paine’s thinking along social and political lines, or led onto these, or stood him in stead, when he took up political thinking, as a background.

After leaving school he ran away to sea. Even the “implication” of this suggests an independent, self-reliant and bold character that he displayed throughout his life. It was short-lived, but he went to sea a second time, and later told Clio Rickman that during his time at sea he learned a lot, and that there was hardly a period in his life that he was not learning something. (Rickman, Thomas Clio. The Life of Thomas Paine. Rickman, London, 1819. p.37.) Paine said, “I scarcely ever quote; the reason is I always think.” (Collins, Henry. Introduction to Rights of Man. Penguin Books, 1976. p.12. 7. Robertson, J.M. Biographical Introduction to Rights of Man. Vol.1. A. and H. Bradlaugh Bonner, 1895. p.vii.) The implication again being the education he received at the old “Grammar” School, in “the sciences,” which would be based in the principles reasoning, ie. thinking, and its expression and understanding in clear intelligent “language,” which, again, his whole literary work shows how well he learned its principles.

After his second return from the sea, when he was 20 years old, in London, employed as a staymaker, his father’s trade, for two years, “in which time he zealously studied astronomy and attended the lectures of Martin Ferguson.” This is quoted by Paine himself and repeated in a number of biographical notices, and where Paine says that he bought himself a pair of globes and some instruments. Woodward, quoting Paine, draws attention to him becoming acquainted with Dr. Bevis “of the Society called the Royal Society, then living in the Temple, and an excellent astronomer…” (Woodward. p.30. Rickman. p.37.)

Adam Ferguson was a professor of Natural Philosophy. He wrote a book Civil Society, and another on Refinement, defending the morality of stage plays that were under attack at the time. He had a reputation in the classics, mathematics and metaphysics, and was a friend of David Hume and had visited Voltaire. His lectures were attended by a number of non academic hearers.

Benjamin Martin was a mathematician, instrument maker, astronomer, and travelled giving lectures on Natural Philosophy; he was the author of several books including, “Philological Library of Literary Arts and the Sciences”.

Dr. John Bevis, is said to have had Newton’s Optics, as his “inseparable companion,” and was a proficient astronomer, being a friend of Halley, and himself had discovered a new comet in 1744. He was elected to the Royal Society in 1765, and to the Berlin Academy of Sciences. He was the author of numerous publications. Both Hawthorn and Edwards say that Ferguson introduced Paine to Bevis. (Hawthorn, Hildegarde. His Country was the World, A Life of Thomas Paine. Longman’s, Green and Co., 1949. p.6.) (Woodward. p.30.) (For information on Martin, Ferguson and Bevis see the Dictionary of National Biography, where much information about them appears.)

This clearly shows that Paine, at 20 years old, was for a period of up to two years on intimate terms with at least Ferguson and Bevis, and, we may assume, not only attended their lectures, but read their literature. I obtained my biographical data from the National Biographical Dictionary. When 24 years old, in 1761, Paine decided to become an exciseman. His wife’s fa- ther had been one (she had died some time earlier) and the project found favour. Conway says that Paine “after passing some months of study in London, returned to Thetford in July 1761. Here, while acting as a Supernumerary officer of excise, he continued his studies, and enjoyed the friendship of Mr. Cocksedge the Recorder of Thetford.”(Conway, Moncure D. The Life of Thomas Paine. Watts & Co., London, 1909. p.7. 13. Rickman. p.36.) Rickman says that Paine 1761 “went back to Thetford for 14 months to study for an examination. “This would seem to suggest that he “went back” for one of two reasons, or both, to stay with his father, and/or utilise the facilities of the Thetford Grammar School.

Here, again, we must notice the educated class of person Paine so easily got acquainted with. I might also mention here Benjamin Franklin, though I will leave it as just an aside until I come to deal with him later. But mixing in such company so freely indicates that Paine was fulfilling his claim to have always been “learning” something. It indicates to me that he combined a natural learning capacity combined with a strong desire to take every opportunity that was offered or was available.

He passed his examination for the Excise and took up various stations for a few years until in 1768 he was stationed at Lewes in Sussex. (Conway, p.9.)

Paine was born into a poor family and stated, “My parents were not to give me a shilling, beyond what they gave me in education, and to do this distressed themselves.” (Ibid. p.5.) He also said, “the natural bent of my mind was to science.” In his almost continuous condition of poverty, it highlights a determination to educate himself beyond what his father could do for him, and it emphasises his ability to impress those above his own position in life.

The condition of the people of England at these times was a deplorable one, and that of the excisemen no better, if not worse, if that was possible. So it would seem that because of the better education and ability of Paine, he took on the work to state their case for a rise in salary by a petition to both Houses of Parliament, and so came about his first publication, The Case of the Officers of Excise, which was written in 1772 and published in 1773, an edition of which I possess was published by W.T. Sherwin in 1817. (Rickman. pp.40-41.)

Here we see Paine at 35 years of age already in possession of the fundamental powers of strong logical reasoning, clear observation and understanding of the case he was presenting; a command of language and expression, and a co-ordinated presentation of the points he wished to bring to the attent- ion of his readers.

If there is any problem about his writing Common Sense after he went to America, it is right here that it should start in his Case of the Officers of Excise. Right through the pamphlet of 16 pages there is unmistakably the basis for all his writing that followed. He marshalls the points of case in the same way as in his later works.

Paine takes the various seasonal conditions under which the excisemen worked, their living expenses in detail, their duties, temptations to bribery, lack of incentive, details of the particulars of their work when away from home, maintenance of their horses, the time away from home, the total cost of their expenses as against their salary, and arrives at one shilling and nine pence farthing a day for a man on 50 pounds per year. The case for an increase in salary he builds up would do credit today to a union advocate before the arbitration court, and not only on the physical side, but on the moral and human side.

He punctuates his case by such remarks as forecast those that he presents in Part 2 of his Rights of Man, such as (he is referring to the temptations to bribery): “The bread of deceit is the bread of bitterness; but alas! How few in these times of want and hardship are capable of thinking so? Objects appear under new colours, and in shapes not naturally their own; sucks in the deception, and necessity reconciles it to conscience.” “He who was never an hunger’d man may argue finely on the subjection of his appetite; and he who never was distressed, may harangue as beautifully the power of principle. But poverty, like grief, has an incurable deafness, which never hears; the oration loses all its edge; and To be, or not to be,’ becomes the only question.”

In this last extract there is an internal link in his thinking with a similar expression in his Crisis No.1. – “POVERTY, LIKE GRIEF, HAS AN INCURABLE DEAFNESS.” Right at the opening of Crisis No.1., we have the words: “TYRANNY, LIKE HELL, IS NOT EASILY CONQUERED.”

“The Woodward says, “Paine spent the whole Winter of 1772 in trying to get Parliament to take some action,” but the Case was a complete failure. Commissioners of Excise said there were so many applicants for places in the service that any officer who was not satisfied with his pay was welcome to quit, and they would be able to fill his place immediately.” (Woodward. p.51.)

I have already mentioned that Paine had made the acquaintance of Franklin, to whom he was introduced by Oliver Goldsmith. Franklin represented the American Colonies in London from 1764 to 1775. Samuel Edwards says, “Through Oliver Goldsmith (Paine) had become acquainted with…Benjamin Franklin. But when, in the period mentioned, is not stated. It seems that Paine kept green in his thought contact with Goldsmith, as he seems to have done with Franklin, who enough of his ability to give him a letter of introduction to friends in Philadelphia and advise him to migrate there.”(Edwards, Samuel. Rebel! A Biography of Thomas Paine. New English Library, 1974. P.33. Conway, p.15.)

While at Lewes, in the meantime, though, and where Paine settled for years, 1768-1774, (Rickman, 1768, p.37 to 1774, p.41.) He became a notable, even being elected to the Town Council. (Collins, note p.13.) Collins says that he “became something of a celebrity Lewes, not only through his work on the Council, but mainly as a and well-liked member of the Headstrong Club, a discussion-cum-social society which met at the White Hart tavern, a few yards from his lodgings” was also appointed one of the two constables for Lewes. (Ibid. p.13.)

I have written of Paine’s biographers failing to follow-up the implications before of what is known, however vague, about the early days and activities he went to America. I feel that tremendously important implications were not followed up sufficiently by such as Conway, Gilbert Vale, and Clio Rickman. Conway says that after Paine left Lewes he went to London, but it is not known how he lived physically, but he quotes from a letter by Paine indicate how he lived mentally. It is written later than the Rights of Man, which is mentioned in it. (Conway, p.15.) It is written to John King, “a renegade,” and refers to when he and Paine met. In it Paine writes: “I was pleased to discuss with you under our friend Oliver’s lime tree those political notions, which I have since given to the world in my Rights of Man (here we have a valuable piece of evidence that while at Lewes Paine was discussing “political notions” that he later gave the world in his Rights of Man) You used to complain of abuses, as well as me, and write your opinions of them in terms what then means this sudden attachment to Kings?”

Conway says that this Oliver was “probably” the famous Alderman of London who was imprisoned in the Tower during the great struggle of that city with the government when John Wilkes was Lord Mayor. Now, if this was so, Paine discussed with King “those political notions” later incorporated the Rights of Man, Raine must have already developed these before going to America, and under their “friend” Oliver’s lime tree, who in turn was intimately mixed up with the Wilkes business to have been confined to Tower of London? And yet Conway leaves it here without further investigation.

Conway tells us that Paine in early life “cared little for POLITICS, which seemed to him a species of jockyship.” There is a very vague, even meaningless statement, “How early in life?” And does politics include systems of government? But Conway does go on to say that, “the contemptuous word (jockyship) proves that Paine was deeply interested in the issues which people had joined with the king and his servile ministers. (Ibid. p.15.) Did Paine by “jockyship” simply mean the “art of playing politics”? I think so.

Collins in a footnote says, “The discovery that Paine served on the Lewes Town Council was made as recently as 1965 by Leslie Davey of Lewes, member of the Thomas Paine Society. (Collins. p.13.)

The White Hart “Headstrong Club,” says Rickman kept a book of activities called the Headstrong Book, which was no other than an old Greek Homer which was sent the morning after a debate to the most obstinate haranguer of the Club. (Rickman, pp. 38-39.) In it was a statement that it had been “revised and corrected by Thomas Paine,” and it contained the following:

Eulogy on Paine

Immortal Paine, while mighty reasoners jar

We crown thee General of the Headstrong War;

Thy logic vanquished error, and thy mind

No bounds, but those of right and truth, confined:

Thy soul of fire must sure ascend the sky,

Immortal Paine, thy fame can never die:

For men like thee their names must ever save

From the black edicts of the tyrant grave.

Rickman says that Paine as an excise man at Lewes was a Whig in politics, and “….notorious for that quality which has been defined as perseverance in a good cause and obstinacy in a bad one. He was tenacious of his opinions, which were bold, acute and independent, and which he maintained with ardour, elegance and argument.” (Carlile, Richard. The Republican. Vol. V. 1822. See article pp.291-296, where there follows a full reprint of Wilkes’ famous article from No.45 of his North Briton.)

One series of events that Paine became interested in, but a silent spectator of, was the fight by John Wilkes against the British Parliament for the right to report and criticise the proceedings of Parliament. Years later Paine said that he had been deeply moved by the ideas which Wilkes had expressed in his writings (Conway, p.16.) Wilkes’ platform was, 1. Reform of Parliament. 2. Enfranchisement of the lower classes. 3. Suppression of rotten boroughs. 4. Protection of individual liberty.

To completely understand Paine one must understand the political, social and living conditions of the people from whom he came and among whom he grew up. His whole life and writings show this.

Wilkes was elected to Parliament when Paine was 17 years old, in 1757. Wilkes was a Whig and fell out with the Government over his criticism of the King’s Speech, which traditionally was recognised as having been written for him by the Prime Minister, who had been a friend of Wilkes. To have a platform for his criticism, Wilkes established a paper called the North Briton, in number 45 of which he severely criticised the Speech under the impression that it would be taken as a criticism of the policy of the Government. But not so. Wilkes was charged with high treason, but escaped France, and was outlawed, and his seat in Parliament declared vacant. The developments became too complicated to detail here. The public took up the cause of Wilkes, who later was elected Lord Mayor of London amid a series of public demonstrations, riots, petitions, etc. Three times Wilkes stood for Parliament and was three times elected, and three times the seat declared vacant, until elected again for a new seat no action was taken to unseat him, and which has been acclaimed a victory for the right and freedom of the press to report and criticise proceedings of Parliament. Wilkes became the hero of the people. Richard Carlile said, “No other name, hor the conduct of no other person, save the late Queen, ever agitated the country so much as the name and conduct of Mr. Wilkes did after the publication of the North Briton…..such was the clamour for ‘Wilkes and Liberty’ that the phrase was common within the walls of the palace…” The events must have had an important influence on the formation of Paine’s ideas and attitude to the Government of his day.

Conway says that Paine’s “studies of the Wilkes conflicts (were) a lasting lesson in the conservation of despotic forces. “Franklin witnessed it. Paine grew familiar with it. And to both the systematic inhumanity and injustice were brought home personally. “Franklin recognised Paine’s ability.”

Eric Foner, in his Tom Paine and Revolutionary America, says (p.6), “Like so many other figures of the eighteenth century, Paine’s thoughts about the political and social world were influenced by Newtonian science. (Foner, p.8.) The Newtonian universe was one of harmony and order, guided by natural laws. And “Newton was not orthodox, being some kind of Unitarian,” as disclosed after his death. He wrote in a letter on the “Corruptions of Scripture” relating to the doctrine of the Trinity. (Robertson, John M. History of Freethought, Ancient and Modern to the Period of the French Revolution. Watts, London, 1936. pp.668-9.)

With the picture I have presented it is easy to see why Benjamin Franklin became interested in Paine. Franklin founded the Philadelphia Library in 1721, and established the American Philosophical Society in 1744. He obtained degrees from Oxford and Edinburgh in 1762, and was elected to the Royal Society. His style of writing and expression was expressed by a fellow scientist, Sir Humphrey Davy, thus, “The style and manner of his publication on electricity, are almost as worthy of admiration as the doctrine it contains. He has endeavoured to remove all mystery and obscurity from the subject. He has written equally for the uninitiated and for the philosopher, and he has rendered his details amusing and perspicacious, elegant as well as simple. Science appears in his language, best adapted to display her native loveliness. He has in no instance exhibited that false dignity, by which philosophy, is kept aloof from common applications.” (Amacher, Richard E. Benjamin Franklin. College & University Press, New Haven. PP.144.)

I must compare that with what Rickman says about the style of Paine’s writing. Paine is speaking: “In my publications I follow the rule I began, that is to consult with nobody, nor let anybody see what I write till it appears publically” (Rickman notes that Paine was so tenacious on this subject that he would not alter a line or word, at the suggestion even of a friend. “I remember,” notes Rickman, “when he read me his Letter Dundas in 1792, I objected to the pun MADJESTY as beneath him; ‘Never mind,’ he, said, ‘they say MAD TOM of me, so I shall let it stand MADJESTY.” Rickman continues, “were I to do otherwise (let others influence me) the case would be that between the timidity of some who are so afraid of doing wrong that they never do right, as if the world was a world of babies in leading strings, I should get forward with nothing. My path is a right line, as straight and clear to me as a ray of light. The boldness (if they will have it so) with which I speak on any subject is a compliment to the person’s address; it is like saying to him, I treat you as a man and not as a child. With respect to any worldly object, as it is impossible to discover any in me, therefore what I do, and my manner of doing it, ought to be ascribed to a good motive. In a great affair, where the good of man is at stake, I have to work for nothing; and so fully am I under the influence of this principle, that I should lose the spirit of pride, and the pleasure of it, were I conscious that I looked for reward.” (Rickman, pp.64 & 66.) This illustrates how sure Paine was about what he wanted to say.

Paine’s personality is given by Rickman, who knew him both at Lewes before he went to America, and when he returned to England, and in whose house in London Paine lived and wrote some of his famous works. He was, Rickman tells us, about five feet ten inches tall, rather athletic, shouldered, stooped a little. His eye had “exquisite meaning,” was brilliant, singularly piercing, and had in it the “muse of fire.” hair “cued” (a twist of hair at the back of the head), with side and powdered, like “a gentleman of the old French school.” Easy and gracious manners. “His knowledge was universal and boundless.” Among friends his conversation had “every fascination that anecdote, novelty and truth could give it.” In mixed company and among strangers he said little, and was no public speaker. (Ibid. p.xv.)

Paine’s character I would say was clearly studious, highly intelligent, logical, scientific, self confident, a consecutive thinker who thought out an idea from premise to conclusion. He knew what he wanted to say and said it fearlessly. He had strong human sympathies, great powers of observation and penetration to get to the heart of a problem. In these and other characters he was very similar to Benjamin Franklin, which I think was the key to Franklin’s interest in him, particularly after he had read his Case of the Officers of Excise, in which Paine’s ability to gather together, sum up and state the excisemen’s case. In fact Franklin’s style of writing was similar to that of Paine. Franklin was long sighted as to the future of the American colonies, and I feel sure that there was some deep-seated purpose in him advising Paine to go there. Everything in Philadelphia seemed all set-up for Paine when he arrived there, ready for him to fall into, with a job as editor of the Pennsylvanian Magazine which Conway says was a “seedbag” for Paine to “scatter the seeds of great reforms….” In about fourteen months he had actually published Sense, with the assistance of Franklin. Paine had arrived in America November 1774, and the following October he said that Dr. Franklin proposed giving him such materials as “were in his hands towards completing a hist- ory of the present transactions…I had the formed the outlines of Common Sense, and finished nearly the first part…” (Conway, p.27).

Paine, I am sure, was never “just” an exciseman, a teacher, staymaker, or storekeeper. His mental activity, interest in science, government and human relations, implied that there was far more bigger and grander things for him to do. But, his meeting with Franklin, seems to me, to have been the turning point that led on to those things.