By Audrey Williamson

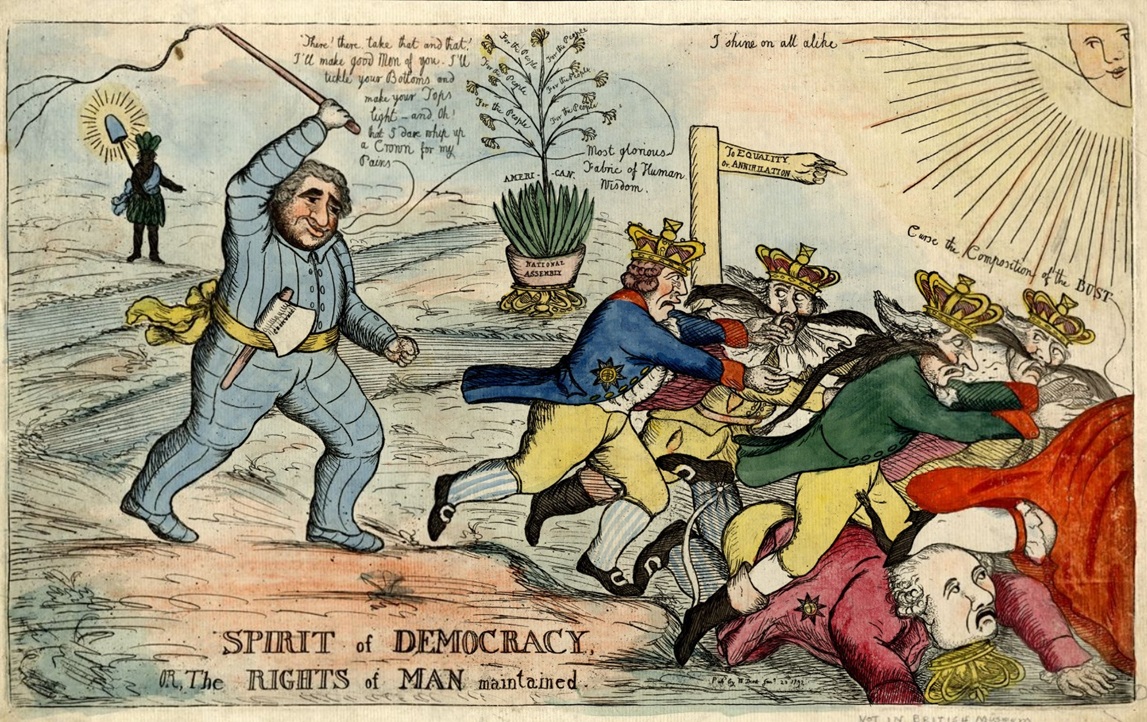

THE SOCIALISM WHICH first emerged in 19th century England was not an isolated phenomenon, but like all political movements had its roots in the past. Directly, it extended back to Chartism, and through this to Thomas Paine and his influential works, Rights of Man and The Age of Reason. Both books were censored under English law and anyone printing or selling them suffered imprisonment or transportation.

Nevertheless, Paine’s works were still sold underground on a huge scale from the 1790s, when they were written, and through to the time of the Chartists. Ri ts of. Man was known as “the Chartists’ Bible.” And although Chartism and its direct aims died out, its ideals survived in the new field of socialism, influenced both by Marx and by Paine.

Paine however was by no means the first or only 18th century radical either in politics or religion. Some would say the movement actively began with John fakes; others that Rousseau and his Social Contract as being the original inspiration. Others point to the great influence, not only in France where it helped to aspire the French Revolution, of the group called the philosophes, and of Voltaire. Voltaire and Rousseau both came to England; and Jean-Paul Marat, when a young physician, lived here and proclaimed himself a follower of Wilkes.

Actually in England some had started acting a century before. Those were the Levellers and Diggers of Cromwell’s time, and in particular John Lilburno, who in 1637 was tried and flogged for the distribution of what today we would call radical literature. “I am a free man, yea, a free-born citizen of England,” declared Lilhurne when brought before the Committee of Examination, and the literature of the Levellers poured out between the years 1645 and 1653. One of the writers, Richard Overton attacked not only the lack of a free press but suggested a Parliament freely elected by all men. Universal suffrage, no less!

Early in the 18th century certain craftsmen and tradesmen were already banding themselves together to protect their interests. Tailors and weavers were particularly active in this way, and strikes were by no means unknown in the 18th century. As yet there were no Combination Laws to prevent this incipient form of trade union.

That was lacking, and lacking almost entirely, was the average person’s right to any active intervention in Parliament. Very few had the vote, and none below a cert- ain income; while growing manufacturing towns, like Manchester, were still allowed no representation in Parliament at all.

Freedom of the press and of speech wore the other major 18th century issues, and this was the basis of the notorious John Wilkes eruption and the”Wilkes and Liber- ty!” cry which soon echoed among crowds throughout England. Wilkes was Member of Parliament for Aylesbury He had an independent free spirit and disliked corruption in high places and at Court, and with his friend, the poet Charles Churchill, he started a journal called The North Briton, which was a continual source of irritation to. the king and government. Wilkes was soon charged with “ceditious libel,” a censorship charge on which Thomas Paine read also later arraigned for writing Rights of Man.

Wilkes did not wait for his trial: he took off for Paris as Paine did in similar circumstances some years later. After four years, however, Wilkes got tired of exile and announced his intention to return and stand for Parliament. Although he was arrested and tried for seditious libel, as expected, and incarcerated in the King’s Bench prison, he carried on from there by proxy a lively election campaign and was returned for Middlesex with an overwhelming majority. The government promptly declared his election was null and void. Two further elections were held, with the same result. After which the House of Commons announced that Wilkes’ rival candidate, who had polled only a few votes, was the new Member.

All hell broke loose! “Wilkes and Liberty” crowds grew, and in spite of a military charge which killed some of them continued. Wilkes’ plight even stirred freedom- lovers across the Atlantic – the later architects of the American Revolution – who sent him letters of congratulation, hampers of food, and even live turtles. When released in 1770 he went on a triumphant tour, one of the towns he visited being Lewes in Sussex, where an Exciseman named Paine was living and working. Paine was already involved in Lewes parish affairs, sitting on the local Vestry which helped widows and orphans, and also attending meetings of the early form of Town Council.

While in Lewes, Paine was persuaded by his fellow excisemen to write a pamphlet on their behalf, The Case of the Officers of Excise. It was a clear plea for better wages, and it also set out certain principles about poverty and crime rarely made at that time. Ile who never was a hungered,” wrote Paine, “may argue finely on the subjection of his appetite….The rich, in ease, and affluence, may think I have drawn an unnatural portrait; but could they descend to the cold regions of want, the circle of polar poverty, they would find their opinions changing with the climate….”

Paine when he wrote his pamphlet was thirty-five years ago. He took the pamphlet to London and distributed it among Members of Parliament, and here met Benjamin Franklin, who had common scientific interests and gave him a letter of recommendation to his son-in-law in America. Paine’s long history as a supporter of the American Revolution, soon to break out, and of human and political rights, had begun.

He was away thirteen years, in the meantime the radical movement in England grew. Wilkes in the end won his way back into Parliament and became not only an Alderman of the City of London but in 1774, the year Paine sailed for America, Lord Mayor.

It was Wilkes who in 1776 put forward the first Motion in Parliament for a wider and more (steal representation. In 1780 a great protest meeting was held in Westminster Hall attended by Charles Fox, Wilkes, General John Burgoyne (the ‘Gentlemanly Johnny’ of Shaw’s play, The Devil’s Disciple, who after his army service in America became a very liberal M.P.) and other reformists demanding annual parliaments(they we then elected only every seven years) and universal suffrage. The same year a follower of Wilkes and later Paine, the radical parson, John Horne Tooke, helped to found the Constitutional Society. This was to revive and become an active element in the radical politics of the 1790s, when Paine came back to England and wrote Rights of ‘an in answer to Burke’s attack on the French Revolution. Similar societies proliferated and one of them, the London Corresponding Society, ran the first largely working-class society, led by a shoemaker, Thomas Hardy.

This radical activity was very much linked with the dissenting movements in religion, and also the scientific discoveries which came in the wake of the Industrial Revolution. A Unitarian chapel was opened.in London in 1774, with Franklin among the attenders. Another Unitarian present was Dr.Joeeph Priestley, the great economist and discoverer of oxygen, who was an active writer on liberty as well as chemistry and theology. In Loren, Paine had married into a Unitarian family. Radicalism spread to the dissenters because like the Catholics they had no political rights in the state; and the fight for their rights and civil liberties irrespective of religion, was a part of the 18th century Enlightenment and rebellion.

In France it had been led by Voltaire, and the philosophes whom Wilkes knew in Paris included D’Alembert and Cideret, the editors of the great Encyclopedia of human knowledge which was one of the wonders of 18th century learning. Years later, the bookseller and writer Richard Carlile published Diderot as well as Paine, and served long terms of imprisonment for doing so.

Rationalism was part of the Enlightenment, and when Paine wrote The Age of Reason he was only putting into his own original form the criticism of the bible and organised religion which had been going on increasingly throughout the century. “All natural institutions of Churches,” wrote Paine, “….appear to me no other than human inventions set up to terrify and enslave mankind and monopolise power and profit.” He thus almost literally anticipated Marx’s later famous phrase about religion being the opium of the people.

Another rather radical society to which Priestley belonged was the Lunar Society of the Midlands, a kind of middle—class club formed partly of manufacturers such as the potters Josiah Wedgwood and Matthew Boulton, and the scientists and writers such as James Watt, inventor of the steam engine, and Erasmus Darwin, grandfather of the evolutionist Charles Darwin. At this time there was still hope that the Industrial Revolution might be used to benefit the workers as well as the management.

William Godwin, author of Political Justice (1798), actually believed that social justice would eradicate all crime. Dr. Richard. Price was another of this school, believing in the ‘perfectibility’ of man. It was his discourse hailing the French Revolution which sparked off Burke’s bitter rejoinder, “Reflections on the Revolution in France” or “Reflections on Behalf of the English Government,” as they might be called: for Burke received a pension for this work. Price was also an economist of long standing, whose Observations on the Nature of Civil Liberty had been a bestseller in 1776. He was well-known in America, where he received an Honorary Degree alongside George Washington.

Dr. John Jebb, who died in 1786, was another Unitarian founder of English radicalism. “Equal representation, sessional Parliaments and the universal right of suffrage, are alone worthy of an Englishman’s regard,” he wrote. He was a real revolutionist, believing that reform would not come through Parliament but through “the active energy of the people.” Another was Major John Cartwright, who ruined his naval career by refusing to fight the Americans.

The political principles at the base of the radical societies came largely from Rousseau. “It is contrary to the law of nature,” Rousseau had written, “that the privileged few should gorge themselves with superfluities, while the starving multi- tude are in want of the bare necessities of life.” This was in 1755, in a work called A Discourse on the Origin of Inequality. A few years later his Social Contract opened with a cry that went around the world: “Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains.”

Godwin’s Political Justice attacked government, imprisonments and transportations, private property and organised religion, but escaped suppression because it cost three guineas, which the government believed was far too dear for the book to reach the lower classes. Rights of Man sold cheaply, and reprinted by the revolutionary societies, was more dangerous. So was Paine’s practical analysis of the economical possibilities of equality, education, the unionisation of workers and a welfare state. The government launched a campaign of vilification against Paine and in his absence (he had gone to France to take a seat in the National Convention) tried him for seditious libel, and won.

In 1794 they instigated trials for treason against Horne Tooke, Holcroft, Hardy, Cartwright and eight others. In this case they failed for lack of evidence. But next year the government under Pitt repealed Habeas Corpus and soon afterwards the new Combination Laws prevented any congregations of workers, or indeed ordinary people, whatsoever. England became virtually a police state.

The amazing thing is that despite this, the movement continued to flourish underground. So did the subversive literature. Pig’s Meat was the title of one of the workers’ journals — one of many to describe lampoons on Burke’s notorious reference to the “swinish multitude” in his Reflections. Over a century later Bernard Shaw wrote in his Preface to Man and Superman: “Tom Paine has triumphed over Edmund Burke, and the swine are now courted electors.”

Another democratic journal was Politics for the People, and yet another Tribune: a name resurrected by Aneurin Bevan and Jennie Lee when they founded the journal for which many left-wing politicians write today. Even the radical poet, Robert Burns,’ The Tree of Liberty, took its title from a piece of the same name written by Paine.

Burns was not the only poet to echo popular radical ideas. Much of William Blake’s elaborate poetic symbolism was invented as a cover for his radical ideas when these became subject to prosecution. And in the next generation Byron and Shelley, who was the son-in-law of William Godwin and Mary Wollstonecraft, author of Vindication of the Rights of Women – carried on the radical tradition. “That great and good man”was Bhelley’s description of Paine, at a time when Paine was still reviled in his native country.

What we owe to Paine, and those who kept his works in circulation in spite of per- secution, is incalculable. He first set working men on the way to genuine participation in government, and the poor on the path to the welfare state. He suggested family allowances, old age pensions, and set out economic schedules for these things. He attacked slavery almost on setting foot in America, almost a century before Lincoln, and attacked war as an outmoded form of settling international disputes. “The conquerors and the conquered are generally ruined alike.”

All disputes, he said, should be settled by arbitration treaties. It was this idea or Paine’s that consciously inspired President Woodrow Wilson when he founded the League of Nations. The United Nations today is inherited from Paine’s suggestion.

Basically, like all the greatest writers on liberty, Paine was a humanitarian. “My country is the world and my religion is to do good,” he wrote, and it is one of the inscriptions on the base of his statue in his native Thetford. Freedom, in Paine’s view, could not be dissociated from political morality, and he sounded a warning note which still carries a message:

“He that would make his own liberty secure, must guard even his enemy from oppression…”