By R.W. Morrell

The Adam Of A New World. Documents illustrating radical political activity in England, 1789—1805. Helio Osvaldo Alves. 334pp. Paperback. University of Minho, 1985.

The sub-title of this work indicates its nature and scope, for by far the bulk of the book is taken up with extracts from the literature which charts the political ferment in Britain, rather than simply England, as the author states, generated by the revolution in France. Many of the writers of these works are well known, or should be, to students of social and political change in Britain, and their influence, although here offered in a geographically restricted context, was far more widespread than many readers may think to be the case. Paine looms large in these pages, as rightly he should for his works had an enormous popular impact, but the first extract offered is taken from a letter written by Burke, and this is followed by a galaxy of the famed and the not so famous, indeed some of their rues we may never know as they wrote anonymously. One and all, though, they contributed to what was a furious debate and in some instances reflect what we might now term ‘grass-roots’ opinion.

Of course debate and action went hand in hand, with the authorities taking most of the action through the application of bans, prescriptions and harsh laws which penalised open discussion at a popular level, for it was the mass of the people being influenced to demand change which authority most feared. Paine would never have been prosecuted had his work been restricted in circulation to a certain strata of society and written in intellectual jargon, perhaps even Latin. The ‘feel’ of the debate comes over to the reader from Professor Alves’ pages, and one also sees how relevant much of it still is when reading of events in certain nations today, notably South Africa. In some respects despite the harsh penal laws of 18th century Britain the governmental response to popular agitation for reform, though harsh, could be said to be rather sore humane than in the South Africa of the 1980s.

The extracts given bring out the complexity of the agitation for change, and the material presented in the book gives the stance taken by the opposing factions. The issues being argued over were not simple for in many respects the demands being made for change were quite drastic, as can be seen by glancing at some of Thomas Spence’s ideas. If Paine was seen by the establishment as a dangerous radical he was moderate by Spence’s standards, indeed Spence did not spare Paine any criticism. Whatever else it was the debate reflects deep human feelings – in most instances there was nothing artificial about it, though the sincerity of certain individuals, notably Burke, is suspect.

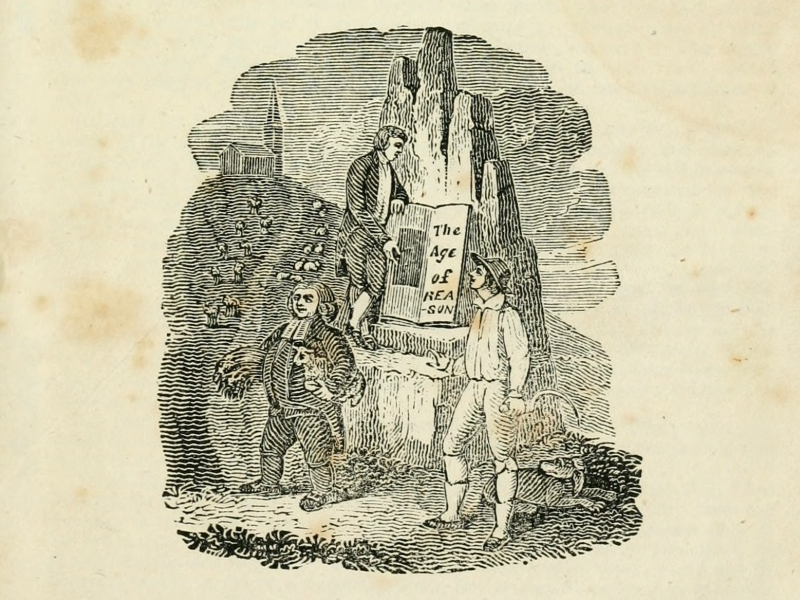

The book is divided into eight sections, each having a brief but adequate introduction, which chart the development of the debate. The section titles are worth noting: The impact of the French Revolution; 1789-1191, The Spring is Begun: 1791-1792, The Conservative Backlash: 1792-1793, The Radical Response; 1792,1793, The Treason Weis and Beyond; 1291-1795, The Age of Reason; 1794-1800; Transition; 1796-1799, The Adam of a New 1797-1805.

There is a valuable set of chronological tables dated from 1789 through to 1805 (pp, 297-308) followed by a series of biographical sketches which commence with Joel Barlow (1754-1812) and finish with William Wordsworth (1770-1850), the whole section taking up eight pages. The book is completed by a select bibliography and an index.

Of course the work leaves off with the debate unresolved, thus making the final extract, from Blake’s poem beginning, ‘And did these feet in ancient time’ rather apt, for it suggests further conflict, and as students of British social history well know, this case in plenty before many of the radical reforms being promoted became realities; some still remain to be achieved.

It would be difficult, if not impossible, to present within a single volume fully comprehensive coverage of the literature which the French Revolution generated in Britain, and Professor Alves himself drays attention to the exclusion of most examples of Whig radicalism on the grounds that this material is relatively easy to find in modern printed fora, though also noting the focus of his book to be popular radicalism. The selection of material for inclusion in a book of this character must, in the last analysis, be a rather subjective process. Personally I find the material Professor Alves selected offers a very balanced group which serves to introduce its readers not simply to the debate itself, but perhaps even propel them further. Unquestionably this is an important work not just of value to university students, for which it is intended, but also to historians, educationalists and the general reader. It deserves a wide circulation, and as the text is all in English it should hopefully achieve this.