By R.W. Morrell

Tom Paine: The Greatest Exile. By David Powell. 303 plus unpaginated preface. Croom Helm, Beckenham, 1985.

Biographies of Paine are not ten a penny so another to the few which are available is, one hopes, an event to be celebrated, for there is always the hope that here at long last will be a significant addition to the available information on him. Unfortunately this new book, although well written and giving a reasonably comprehensive insight into the background events which the author feels influenced the development of Paine’s thinking, I do not think it gets above the routine.

Paine did not live in an intellectual vacuum, and he seems to have had a very agile and inquiring mind from an early date, plus a dislike for the position in society his background set him. From all accounts he was able to influence various people into helping him, notably Benjamin Franklin, who was almost a second father to him and certainly enabled Paine to find a reasonable form of employment when he arrived in the colonies in America. But the more I study the various claims that this or that event “influenced him” the less convinced I become that we have discovered the main influences. Paine, as he tells us, was passionately interested in science and attended classes in various subjects, particularly astronomy, when living London. He also became friends with various scientists and teachers, and it may not be amiss to bear in mind that Franklin himself was as interested in things scientific as was Paine. Science and technology embodied radical change, and I feel that this was the primary factor which influenced Paine towards a radical and progressive stance, and it is this aspect of his life which all too many authors, Mr. Powell included, do not pay sufficient attention to, although naturally not ignoring the fact of Paine’s active interest in science and technology.

Mr. Powell spends much time, particularly when presenting Paine’s earlier years, in examining background events, though he is not the first to do this, as readers of the late Audrey Williamson’s biography of Paine will know. This technique, while being quite acceptable in historical studies, and certainly placing figures in the context of their day and age, can be dangerous as we are left wondering to what extent the authors’ inclinations are right, and whether this will lead to the creation of a degree of historical mythology. Mr. Powell ignores certain studies of Paine, such as those by George Hindmarch, which argue that Paine was an active writer in his Sussex days as well as a would-be nonconformist clergyman when based in Lincolnshire. The latter would clearly indicate Paine’s inner urge to escape from what was the position in life his birth had destined him for in the socially layered society of England in the 18th century, while the former would indicate the school from which he graduated into journalism, for above all else Paine was a superb writer in a journalistic manner.

Paine’s ideas are still in many cases advanced, far too advanced for some countries, and he appeals to people across the political and religious spectrum, though The Age of Reason does not go down with fundamentalists in the United States and other countries, which highlights the irony of the fact that it was written to combat atheism in France. Had Paine not written this book I strongly suspect he would now be accepted unquestionably in the United States as an unquestioned founding father, but Chapman Cohen was right when he claimed that writing The Age of Reason played into the hands of Paine’s political foes. Mr. Powell certainly highlights the two faced attitude, not to mention the ingratitude, of many of those who had used Paine’s abilities to further their own ends, and this was never more stressed by the almost total official indifference to his death. Times have changed, however, and in both the United States, particularly there, and Britain, recognition is now being accorded Paine at an increasing tempo, though this side of the saga is beyond the scope of this book.

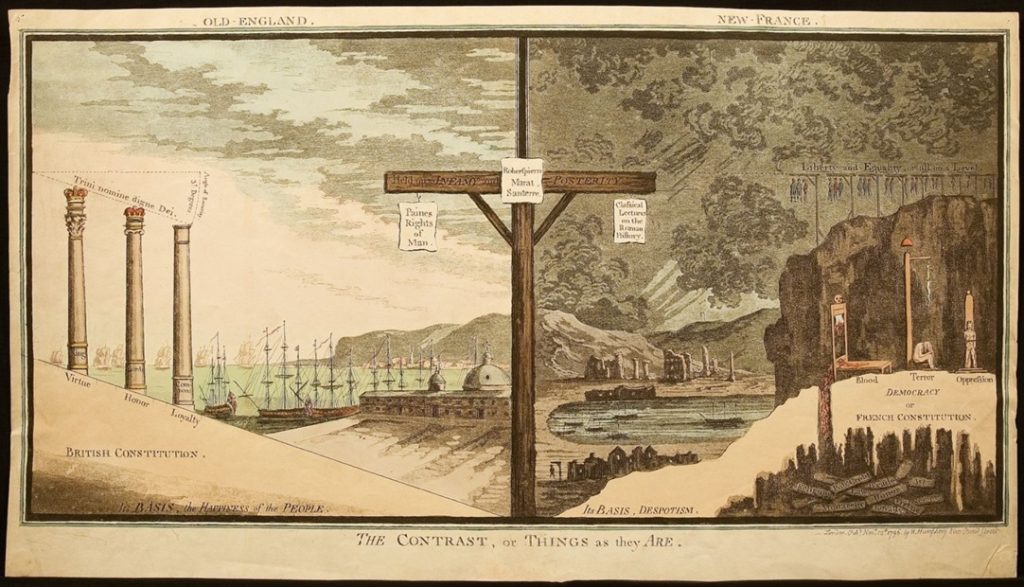

Tom Paine: The Greatest Exile is not a great book, but it is a competently written and very readable study of Paine which can be recommended. What does puzzle me is why it is so highly priced, for this will clearly place it beyond the reach of many who might otherwise buy it. There are no masses of coloured illustrations in it, indeed there are no illustrations apart from the frontis which reproduces an all too familiar portrait of Paine. The definitive biography of the great radical still remains to be written, if ever it can be in view of the all too obvious gaps in our knowledge of Paine.