By R.W. Morrell

To most people the name of Thomas Paine conjures up thoughts of the political struggle for American independence or his defence of the revolution in France against Edmund Burke’s savage and prejudiced, if not ill-informed, attack on it. Many were attracted by his programme of social and political reforms; however, to others Paine’s name is recalled as a critic of revealed religion, and it was this part of his thought which presented his many political enemies with a weapon they used effectively against him. Nor did Paine’s attack on George Washington for failing to assist him when imprisoned in France help, for the reaction this produced revealed to Paine the degree to which the public had forgotten his key role in the American revolution, and also had permitted themselves to be influenced by emotive irrationalism. Paine himself did not realise the extent to which Americans had accorded their first president an almost divine status, and those who criticised him did so at their peril. Of course Washington may have been unaware of the dangerous situation his fellow patriot had found himself in, though in fairness to Paine we cannot be certain Washington was really in the state of ignorance his supporters claim.1

Paine, the man of reason, must have been both astonished and hurt when on arrival back in the United States he discovered the extent to which his enemies had whipped up opposition to him, largely because of his authorship of The Age of Reason, but also because of the letter to Washington. Both were gifts to his enemies, and they made the most of them, as the newspapers of the time show.2 Chapman Cohen may seem to have exaggerated when he asked what was the real cause of the hatred manifested against Paine and answered it as being his authorship of The Age of Reason,3 but reading much the contemporary press treatment of Paine demonstrates all too clearly the truth of Cohen’s claim. These reactions to Paine have coloured the understanding and appreciation of him, and he has been recognised as primarily a political or religious figure, but there is an important feature of his work which has long been neglected, his interest in science. The Age of Reason brings this out vividly, and while Jim Herrick4 is right in his recent book to stress the biblical criticism in The Age of Reason was not original, even if new to many of its readers, he, should have taken note of the fact, as I did in 1968,5 of Paine’s use of science to undermine theological assumptions. Others had hinted at it, but Paine was the first writer to systematically use arguments drawn from science to support his case, and even if he failed to recognise what this would eventually lead to, perhaps because it ran directly counter to the stated aim of his book, which was to promote deism as against atheism, he nevertheless fully grasped the power scientific facts gave him. The revolution in thinking this led to is still very evident.

‘The natural bent of my mind was to science’, wrote Paine,6 but this tells us nothing about when and where this interest arose, and any search for information is hindered both by Paine’s own reluctance to tell us much about his early days as was the loss in a fire after his death of many of his papers. Nevertheless, there are some tenuous clues to be found in The Age of Reason, for here Paine mentions his father’s Quaker beliefs which resulted in him obtaining, ‘a tolerable stock of useful learning’; he was also sent to the local grammar school, though leaving early.’7 It would be interesting to have known what books Paine’s father possessed, particularly those of a scientific character, and also whether there were any teachers at the school rather more enthusiastic about science than classics. Regrettably Paine gives no information on these points; however we can deduce from his comments a hint at the possible origin of his interest in matters scientific.

The elder Paine’s trade was staymaking, so it was perhaps inevitable his son would be apprenticed in this trade; the youngster, though, does not appear to have relished the prospect of a life of staymaking, and an adventurous spirit is suggested from the fact of his running away to sea. It was a short-lived rebellion brought to a rapid conclusion after Paine senior intervened and brought his son back to Thetford. Paine was to try his hand at seafaring for a second time some years later, but this time discovered for himself its shortcomings, nevertheless, he always took an interest in maritime matters and wrote on the subject.

While employed as a staymaker in London, Paine attended lectures in astronomy and natural philosophy, and from his small salary purchased a pair of globes, a deed which illustrates the depth of his interest in science. One wonders what type of people his fellow students were, and the suspicion cannot be escaped from that they came from what in economic terms would be described as middle or upper classes. In such a company Paine, as a manual worker, may have felt inferior, and this could have been the stimulus to prompt him to look for employment which conferred in social terms a higher status, even if the pay was hardly much to shout about. So Thomas Paine, one-time staymaker became Thomas Paine, Exciseman and what we would now term, civil servant. This change in social status would have certainly brought him into contact with even worse people who shared his interest in science, and it was through a member of the Excise Board. L. Scott, another enthusiastic amateur scientist, that Paine was introduced to Benjamin Franklin, who has.been described as ‘the first guardian angel of Paine’s life’, and who was to dramatically change the course of it.’8 In later years when Paine had achieved fame, caricaturists like James Billray were quick to call attention to his original trade.9

The lectures Paine attended in London were given by Benjamin Martin and James Ferguson, and he later became acquainted with Dr. John Bevis, a Fellow of the Royal Society. Martin was a mathematician and instrument maker, and, as Daniels has noted,’° a ‘general compiler of information’ with thirty major publications to his name. Ferguson was an astronomical lecturer and, like Martin, an instrument maker as well as author of various books, notably, Astronomy Explained upon Sir Isaac Newton’s Principles, first published in 1756, and followed by many more editions. An active lecturer, much in demand, he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1763. John Bevis was a medical man but astronomy was his real passion, He assisted Edward Halley, and, according to Daniels,11 his favourite reading material was Newton’s, Opticks. These lectures, probable discussions and reading books recommended by the lecturers, ensured Paine becoming, like his teachers, a follower of Newton, whose vision of a systematic and harmonious universe governed by laws discoverable by human reason was incorporated into The Age of Reason. But Paine was not satisfied to limit Newton’s ideas to the scientific view of the universe and went on to extend them into the social, political and religious fields where, I doubt, neither Newton or most of his followers imagined they applied. But as far as Paine was concerned, they most certainly did, and he strongly maintained the study of ‘natural philosophy, mathematical and mechanical sciences’ to be ‘the study of true theology’.12

When Paine departed for what were then still England’s American colonies, he took with him a letter of recommendation from D. Benjamin Franklin. This is an interesting document for it clearly presents Paine as a person well versed in matters scientific. The recommendation suggests Paine could be employed, among other things, as an assistant surveyor. A surveyor in the 18th century could well be a geologist, for this was not then a recognised profession. William Smith, who has been dubbed, ‘the Father of English Geology’, serves as an example, for he was a surveyor. The actual name ‘geology’ was itself not coined until 1778 by J.A. de Luc. Survey work, then, could imply some geological knowledge, and we know Paine took an interest in the subject for he published an article in the Pennsylvania Magazine in February 1775 under the title, “Useful and Entertaining Hints on the Internal Riches of the Colonies”, which discussed the potential mineral wealth available to America if the nation expanded. Aldridge,13 says this article was written after Paine had paid a visit to “the fossil collection” in the Library Company of Philadelphia. At the time, though, the term; ‘fossil’ and ‘mineral’ were treated synonymously, and it was not until the 19th century before the two terms were fully divorced.14 Paine refers to the collection as being mainly European in origin, with the American specimens consisting of ‘earth, clay, sand,” etc,,, along with descriptive information and locations.’15

The text of The Age of Reason shows Paine to entertain a vision of a long period of geological time. His list of friends and acquaintances included most of the scientific luminaries of the new nation, and he discussed science as well as conducted experiments with a number of individuals, including George Washington, when the two of them did some work on marsh gas. Whether he met J.D. Schopf,16 who wrote the first important work devoted to the geology of part of the United States, we do not know, Schopf, who as a Hessian fought on the British side during the war, stayed on for some time after, but as the book was written in German and published in Germany in 1787, it is to be doubted if Paine knew of it, for he certainly did not read German. He was not alone in being unfamiliar with this important work for it was not until the first English translation appeared in 1972 did many American geologists wake up to the book’s existence. As an editor, Paine published articles on salt, soil and saltpeter. It was an article on the latter, written jointly with Thomas Prior, and published in the Pennsylvania Journal on November 22, 1775, which was the first in America to carry Paine’s own name. The next issue carried a further article on the subject by the two writers, Saltpeter, important in the manufacture of gunpowder, occurs generally in frost-like crusts on the surface, and it was the scarcity of these natural deposits which concerned Paine and Prior, and their joint articles gave particulars of experiments they conducted to produce it. Prior was an army officer, as, indeed, was Paine for a time. Paine knew Charles Wilson Peale, who established the first important public museum in the United States, which was opened in Philadelphia in 1786,17 the year before Paine departed for Europe to promote his iron bridge scheme. He also knew C.F. Volney, who was the author of an important work on the United States which included many observations of a geological character, and who had formed a collection of geological specimens which he took with him when he returned to France. Fossils included in the collection, which were termed ‘petrifications’, exited great interest amongst a number of French scholars. Paine met Volney many times in France and it would be odd indeed if the two, who were both radical in politics, did not discuss geology.

Paine invented what he maintained was a smokeless candle, sending samples to Benjamin Franklin along with an enthusiastic covering letter describing the invention, Hawke claims the invention stimulated no commercial interest and nothing more was heard of then.18 However, smokeless candles made according to the method devised by Thomas Paine were sold in shops in Britain until just after the 1914-18 war, for the late Ernest Smedley, a retired miner living in Hucknall, Nottinghamshire, who collected books on Paine, had preserved one of the labels from the packets of candles and showed me it, so unless there was another Thomas Paine who invented a smokeless candle, there was a very definite commercial interest. Whether the candles were actually more efficient than the none-smokeless variety is uncertain. Paine’s candles had holes in it to permit the passage of air, which, he told Franklin, allowed the smoke to leave at the opposite end to the flame. Paine’s biographer, W.E. Woodward conducted some experiments with candles made to Paine’s design but found they possessed no advantage over solid candles.19

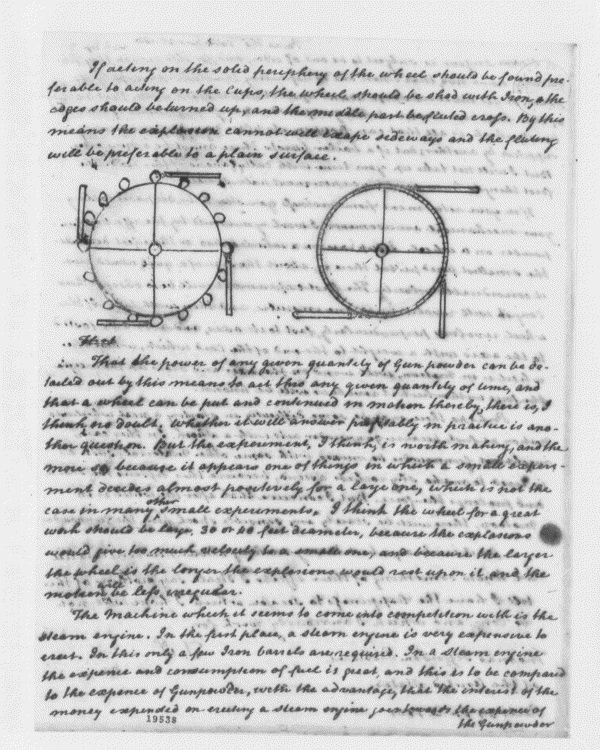

Another of Paine’s scientific interests, which probably followed from his research into the manufacture of saltpeter, was testing the explosive power of gunpowder harnessed to an engine designed to drive paddles on a boat. This ‘internal combustion engine’ was not a success.

Perhaps Paine’s most notable scientific, or technological, project was the promotion of the use of iron in bridge building. Most of Paine’s biographers, not excluding his critics, attribute the second iron bridge to have been erected in England to his design, as set out in his patient. This bridge, which was built to span the river Tyne at Monkswearthmouth, was demolished in the 1920s, but many illustrations of it exist. It was sponsored by a local Member of Parliament. Rowland Burdon, who, like Paine, had taken out a patient for the use of iron for bridge building. Recent examination of the Paine and Burdon patients have established the specifications in both differed fundamentally. Those in Burdon’s patient describe the use of metal blocks for the construction of bridges, indeed, the title of the patient reads; ‘Application of Metal Blocks etc,, to the Construction of Arches’, and in his specifications Burdon notes his invention consists in applying metal on ‘the same principle as stone is now employed, by a subdivision into blocks easily portable’. Paine, in contrast, and in far less precise terms than Burdon, as Stuart T. Miller noted20 compares his design to the web of a spider, presumably having in mind an orb web, and goes on to refer to the curved bars of the arch as being composed ‘of pieces of any length.’ Burdon’s voussoirs, as his blocks are technically termed, have a specific length. Paine, it seems, was fully aware of the difference between his ideas and those of Burdon, for he discusses the differences between his system and the one used in erecting arches in stone in a letter he wrote to Sir George Staunton on May 25, 1789.

Paine’s patient specifications show his ideas to have been far more advanced than most of those who have discussed the second iron bridge seem aware. Burdon’s bridge, as we have seen, was based on iron used as though it was stone; the first iron bridge, the still extant structure at Ironbridge in Shropshire, duplicated in iron the principles of wood construction. Miller, quite rightly holds Paine’s ideas to reveal ‘a far greater appreciation of the potential of iron in civil engineering’, a point which allows him to call into question the claim that parts of an iron bridge made for Paine were incorporated into the Ronksvearmouth structure.21 He argues that the type of iron used in Burdon’s bridge was of the cast variety whereas malleable iron would be required for Paine’s, had it been built. In 1905, Charles Sneider, in his presidential lecture before the American Society of Civil Engineers, summarised the situation when he called Paine’s bridge ‘the prototype of the modern steel bridge’.

But where did Paine first get an introduction to the possibilities for the use of iron in bridge building? His training as a staymaker would have given him an early introduction to the use of tools, and we know at least two of the science lecturers he was acquainted with in London made implements out of Metal, something most would-be scientists had little option but to do themselves. Paine knew and cooperated in America with John Hall, a skilled metal worker originally from Leicester. However, perhaps we must look towards the Sussex town of Lewes as being the place where Paine received his introduction to the potentials inherent in the use of iron, for here a local schoolmaster, Cater Rand, resided and conducted his school at 160 High Street, almost opposite Paine’s own home. But Rand was not only a schoolmaster, he was also an engineer and mechanic, who included the subject amongst a series of lectures he gave in the town. As these classes are not recorded before 1775, the year after Paine left Lewes, it seems unlikely he could have attended, however, Paine was a close friend of the Verral family, who ran the White Hart, which seems to have been one of the intellectual gathering points in the small town. Lucy Verral, the daughter of the landlord of the White Hart, was Carter Rand’s mother. So an introduction through the Verralls was possible. Perhaps, then, it was Rand who first planted the idea for the use of iron in bridge building into Paine’s receptive brain.

What may be claimed as Paine’s most important scientific work, though not without social, hence political, content, was his essay on the cause and elimination of yellow fever, entitled, ‘Of the CMS: of the Yellow fever; And the Means of Preventing it in Places not yet effected with it.” The work was very well received by medical and other scientific opinion and ran to several editions, and despite the general ban on Paine’s works in Britain there was no restriction placed on its publication here. Paine did not discover the cause of yellow fever, which was carried by infected mosquitoes, though in a letter to Thomas Jefferson written in 1803, he suggested it came ‘barrelled up’ in ships from the West Indies, which was near the mark as infected insects were brought into America this way; the discovery that mosquitoes were responsible did not take place until 1887, many years after Paine’s death. But he did accurately identify the breeding habitat of the mosquitoes without, of course, knowing this to be the case, and the introduction of methods to increase the volume of water flow, which would have flooded the stagnant, muddy areas, would have destroyed these breeding grounds thus limiting the number of infected mosquitoes, consequently Paine’s ideas if put into effect, could have played a significant role in helping to control the disease, though perhaps not to eliminate it completely. It is interesting to note his ideas were similar, if not identical, to those of Sir Patrick Manson, an authority on the disease, in.his famous textbook on tropical diseases.22

I do not think anyone would wish to present Thomas Paine as being an outstanding figure in the history of science. His scientific work, varied and interesting, even original, as in the case of his observations on yellow fever, was rather in the nature of grasping the practical implications of ideas. Thus Paine recognised, but did not discover, the value of the use of iron for the construction of bridges, and here his vision was far more advanced than any of his contemporaries. No, Paine’s greatness in the history of science rests more with his literary ability than anything else, for he was the inventor of popular scientific journalism. Many a writer had produced popular books on scientific subjects, at least two have been mentioned earlier in this paper, but where Paine differed from them was in the broad scope of his science and in the presentation of it in a style understandable by the common man. He was, too, the first to fully grasp the dangerous implications scientific discoveries presented in respect to theological claims, and he applied this discovery tellingly in The Age of Reason, however, this fact was lost sight of in the fury of the later dispute between Darwinian evolution and biblical creationism, which has been seen wrongly as the first major dispute between science and religion. Paine laid the foundations of popular scientific journalism and is worthy of being remembered for this, even if his other claims to fame are of far greater consequence.

References

- Hawke, David Freeman. Paine, Harper A Row, NJ. 1974. P.320.

- Ibid, p.53.

- Cohen, Chapman, Naas Paine, Pioneer of Two Worlds, Pioneer Press, London, Nd, pp,50 -52.

- Herrick, Jim, Against the faith, Soto Deists, Sceptics and Atheists, Glover h Blair, London, 1985, p.124.

- Morrell, R,V, “The Relevence of The Age of Reason for Today’, PS Bulletin (1968), 2,3, 10-14.

- Foner, Philip S, Editor, The Life and Major Writings of Thomas Paine, Citadel Press, Secaucus, N,J., 1974, 096 (hereafter Foner).

- Foner, Ibid, p.496.

- Williamson, Audrey, Thomas Paine, His Life, Vork and Times, George Allen and Unwin, London, 1973, p.62.

- Gillray’s, Fashion before Ease; – or, – A good Constitution sacrificed, for a fantastick Fora, of January 2, 1793 illustrates Paine pulling the stay laces of Britannia, Another is, Rights of Man – or – Tote Paine, the little American Taylor, taking the Measure of the Crown, for a new Pair of Revolution Breeches, which was published on May 23, 1791.

- Daniels, R.G. ‘Thomas Paine’s Astronomy’, TM Bulletin (1975), 2, 5, 29-31.

- Ibid.

- Aldridge, Alfred Doan, Man of Realm, The Life of Thomas Paine, The Cresset Press, London, 1960, p.31.

- Edwards, V.N. The Early History of Palaeontology, British Museum (Natural History), London, 1967, pp.40-41.

- Paine, Thomas, Miscellaneous Letters and Essays on Various Subjects, Sherwin, London, 1817, p.9.

- W.A.S., Sarjeant (Geologists and the History of geology, Macmillan, London, 1980) renders the name as Schoepf (Vol.3, p.2068).

- In his book, Mammoths, Mastodons and Man, (Scientific Book Club, 1972, 05), Robert Silverberg gives the year the museum opened as being 1785, More recently, Rudolph H. Weingartner, in a paper, ‘What Museums Are Good For’ (Field Museum of Natural History Bulletin (1984), 55, 8, 17-25), gives the opening date as 1786, which I accept here.

- Hawke, Ibid; p,163.

- Woodward, W.E. America’s Whiner, Secker & Warburg, London, 1946.

- S.T. Miller, ‘The Second Iron Bridge’, MS Bulletin (1975), 2, 5, 5.

- See also the same writer’s, ‘The Second Iron Bridge at Sunderland: A Revision°, Industrial Archaeology Review (1976), 1, 1, 70 72.

- Miller, Ibid.

- R.G.,Daniels, “Thomas Paine on Yellow Fever”, ZPS Bulletin (1971), 2,4.