By Theodore Sizer

Reprinted from an unborn source

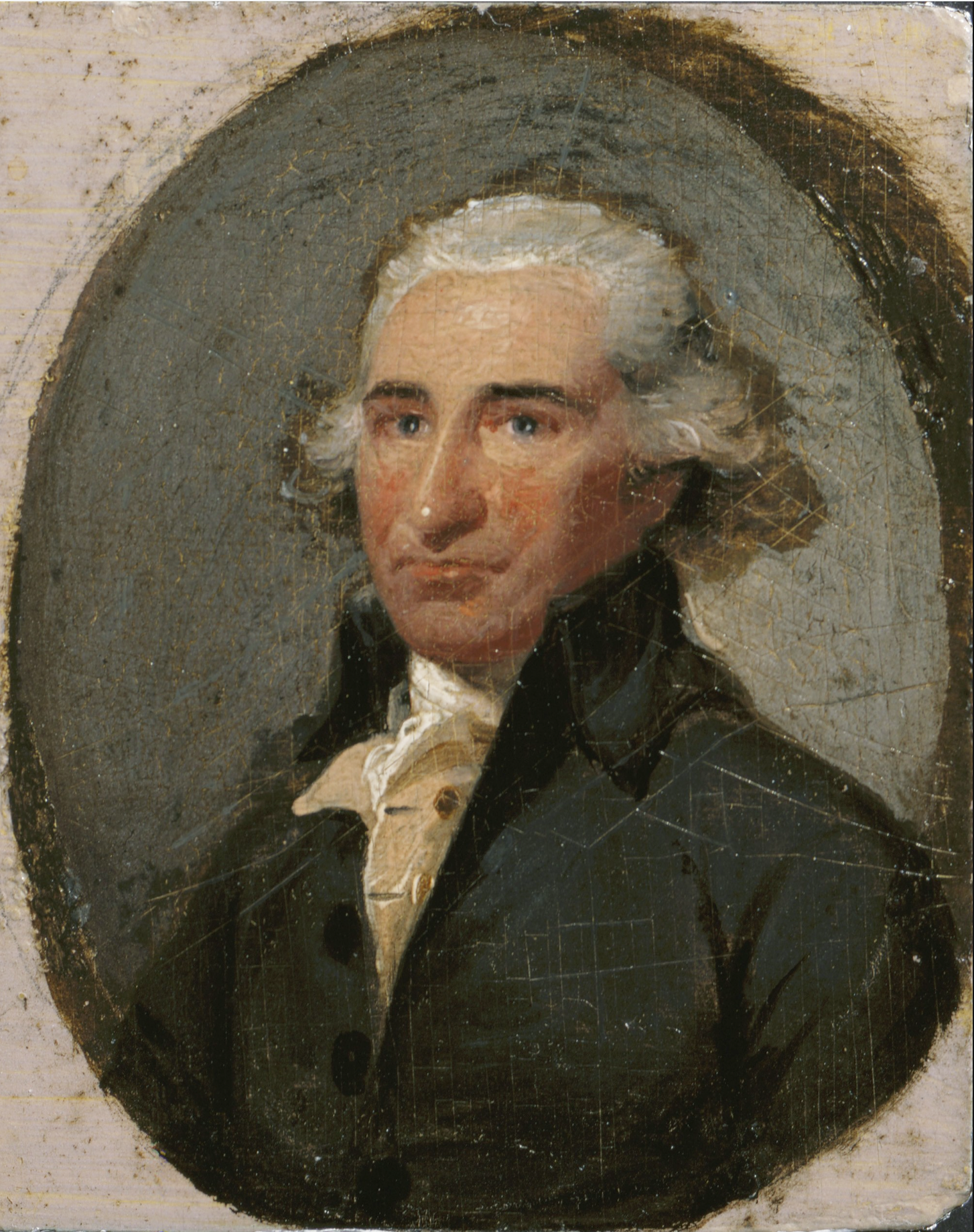

THE tale of the recent discovery of the portrait of the celebrated propagandist, Thomas Paine, painted by the “Patriot-Artist,” Colonel Trumbull, for Thomas Jefferson—a picture which dropped out of sight over a century ago—is worth telling in some detail.

The little portrait was first and last publicly exhibited in Boston two years after Jefferson’s death, appearing in “A Catalogue of the Second Exhibition in the Athenaeum Gallery Consisting of Specimens by American Artists . . . May 1828”, under the notice, “The following are a part of the Collection formed by the late PRESIDENT JEFFERSON . . . [and] are for sale . . . [Item] 316—Thomas Paine,—an original on wood,— Trumbull.” It then faded into oblivion. When the writer’s The Works of Colonel Joint Trumbull, Artist of the American Revolution, was published in 195o by the Yale University Press, it contained the fol- lowing unsatisfactory entry: “THOMAS PAINE (I737-1809), Revolutionary pamphleteer, author of Common Sense; on wood, before 1809, once belonging to Thomas Jefferson; unlocated.”

The Editor of “The Papers of Thomas Jefferson”, Julian P. Boyd of Princeton, was responsible for the first clue to the lost portrait. In March 1955, he brought to the writer’s attention both sides of correspondence which established the date of the sitting and reaffirmed the connection of the three principals, Paine, Trumbull, and Jefferson. The first letter (now in the Pierpont Morgan Library) was written by the Colonel from London to Jefferson in Paris, 19 December 1788:

By the Diligence which leaves town tomorrow morning, you will receive a Box cont’g your Harness & Saddles. The Box likewise contains what further’ Books of your list Payne has been able to procure . . . a little case with two pictures, one of which I hope you will do me the honor to accept, & the other I beg you to be so good as offer to Miss Jefferson:—I almost dispair of its meeting her approbation, but it is all I can do until I have the happiness to see you again:—you would have rec’d both long since for the Vexation I have had with my larger picture, which has left me little Spirits to attend to anything else. .. .

Jefferson replied (letter now in the Princeton University Library) to Trumbull on 12 January 1789:

Thank you a thousand for the portrait of Thomas Paine, which is a perfect likeness, and to deliver you for the other, on the part of my daughter.

The “larger picture,” which was causing such vexation, was, most probably, the “Declaration of Independence,” for which the preliminary sketch was prepared in September, 1786. The artist referred to this subject in these words:

I resumed my labors, however, and went on with my studies of other subjects of the Revolution, arranging carefully the composition for the Declaration of Independence, and preparing it for receiving the portraits, as I might meet with the distinguished men, who were present at that illustrious scene. . . . In the autumn of 1787, I again visited Paris, where I painted the portrait of Mr. Jeffer- son in the original small Declaration of Independence. (The Autobiography of Colonel John Trumbull, Patriot-Arlin (New Haven. Yale University Press, 1953) pp. 146-147. 152.)

From this original portrait in the “Declaration” the artist promptly made three replicas, all in miniature: the first, for Miss Jefferson, which has descended in the family and is now owned by the Estate of Mrs. Edmund Jefferson Burke and is on loan at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; the second for Mrs. John Barker Church, daughter of Philip Schuyler, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; and a third for Jefferson’s friend Mrs. Richard (Maria Had-field) Cosway, wife of the miniaturist, left by her to the Collegio Maria S. S. Bambina at Lodi, Italy. The first of these, one of the two pictures in the “little case” sent to Jefferson in December, 1788, for his daughter, offered, therefore, the best stylistic parallel for its companion, the lost Paine miniature. It should be noted that the present to Miss Jefferson was apparently painted rapidly and on an oblong piece of mahogany upon which the oval was inscribed. This is rather unusual; the sixty Trumbull miniatures at Yale are all cut in oval shape.

In 1947, through the good offices of Alexander Wahl, Director of the New York Historical Society, Mrs. Arthur M. Greenwood brought to the writer’s attention a loosely painted miniature, oval on a rectangular piece of mahogany, said to be of Trumbull’s friend and companion-in-arms, Philip Schuyler. It was published in the Works (on p. 68), under “Unidentified Men” as a “Miniature of an Unknown Man” (Possibly Phillip Schuyller; Estate of Dr. Arthur M. Gleenway, Marlboro. Mass.” (containing a mistake in transcription, for the name was Greenwood). And there the matter rested.

When the Trumbull-Jefferson correspondence was brought to the writer’s attention, he searched his files of “Unidentified Men” and was immediately struck by the stylistic affinity to the “Unknown Gentleman,” from the collection of the late Dr. and Mrs. Arthur M. Greenwood of “Time Stone Farm” (built in 1702), Marlboro, Massachusetts. The miniature had been acquired before 1912 by Dr. Greenwood from a family living in Concord, Massachusetts, who had kept it for years in a button box. Sometime in the past both eyes had been mutilated—done, possibly, by a child or by one who might have hated the rabble-rousing radical, atheistic Paine.

The writer, doubting the Schuyler attribution (Trumbull’s one miniature of Schuyler, painted in 1792 at Philadelphia, is now in the New York Historical Society), turned to the study, at the Frick Art Reference Library, of every known portrait of Tom Paine. The Greenwood miniature came closest to the destroyed portrait of Paine painted by George Romney in 1791-92, known through the fine engraving of 1793 by William Sharp. He next appealed to Colonel Richard Gimbel, United States Air. Force, Retired, Curator of Aeronautical Literature at the Yale University Library, a great collector of Paine’s work. After studying abundant prints, photographs of portraits, Paine’s death mask, and even caricatures, and comparing them with the borrowed Greenwood miniature, the Paine attribution was more or less convincing. It should be mentioned, parenthetically, that Paine left America for England in 1787 and that it is a simple matter to get artist and sitter together during that and the ensuing year, and that all of Trumbull’s miniatures, with but one exception are painted in oils on wood (mahogany).

Still unsatisfied, Colonel Gimbel and the writer went to the Boston Museum and there laid the Jefferson family miniature alongside the still questionable Paine. They fitted like two peas in a pod. Both were painted on rectangular pieces of mahogany, (unusual for Trumbull), which appeared to come from the same plank, though the Greenwood one was on a slightly smaller piece. The painted ovals, however, were identical in size, 4 and ? inches by 3 and ¾ inches.

Even the character of the stains on the backs were the same for both. Stylistically, both were identical, the pigment and the manner of handling it coinciding exactly, except that the Jefferson had been cleaned and newly varnished and the other was dirty, dry, and mutilated. Both were painted in a more sketchy manner than Trumbull ordinarily employed, but then both were intended as presents and were not to be incorporated in historical compositions (as were the sixty at Yale), which were ultimately destined to be engraved. The crackling on the surfaces of both—unusually large—was the same. Both were examined under the ultra-violet light—from the front, back, and sides; similitude was conclusively demonstrated. Greatly enlarged photographs were also studied. The writer is convinced that the Greenwood miniature—in oils on mahogany—is not only the work of Colonel Trumbull, but is the missing portrait of the political agitator, Colonel Gimbel concurring fully in this last. The “perfect likeness,” as Jefferson put it, of Tom Paine, which disappeared in 1828, has been found.

The little unframed miniature, which has the appearance of never having been framed, has been recently lent by Mrs. Greenwood to Colonel Gimbel. It is now on exhibition at the Yale Library, with the 1828 Boston Athenaeum catalogue and photostats of the letters in question, together with a small selection of Tom Paine’s celebrated pamphlets from the Gimbel Collection. Colonel Trumbull, who was born at Lebanon, Connecticut, on 6 June 1756, was a proud, punctilious, and somewhat vain man, concerned alike with his mortal and posthumous fame. It is pleasing that the discovery of the charming little portrait of Tom Paine, long hidden away in a button box, coincides with the coming celebration of the two hundredth anniversary of the birth of the “Patriot-Artist.”