By Bernard Vincent

The 1987 Thomas Paine Lecture, University of East Anglia

As it happens, it was through Thomas Paine that I became interested in early American Freemasonry. While working on my biography of Paine, I was intrigued from the outset by the fact that all of sudden, within just a few weeks or months, as if by magic, he jumped from his obscure humdrum existence in England where he worked as an Excise officer and a corset-maker onto the American literary-political stage, there to became, at the age of almost forty, one of the leading lights of the Revolutionary movement.

How was it that a man who was little short of a failure in his native country became acquainted so rapidly with the met prominent figures in the Colonies, even becoming a friend of theirs in many cases? How can one account for the quickness of his ascent and the suddenness of his glory?

One way of accounting for this, one hypothesis (which has several times been made), is to consider that Paine had become a Freemason and that, as such, he enjoyed, first in America, and then In England and in France, the kindly assistance of certain lodges or of certain individual Masons.

Some time before he left England in 1774, Paine met Benjamin Franklin in London. Franklin, the founding father of Freemasonry in Pennsylvania, and future Venerable of the famous Lodge of the line Sisters in Parte where he was to preside over Voltaire’s initiation on April 7, 1778. In his Revolution and Freemasonry, the French historian Bernard Pay goes so far as to say that it was Franklin himself who then converted Paine to the Masonic creed. But he does not give any factual evidence in support of his assertion. The only thing we know for sure is that on September 30, 1774, on the very eve of his departure from London, Paine was given by Franklin a letter of recommendation for his son-in- law, Richard Bache, himself a Mason and a wealthy businessman in Philadelphia. It was Bache who guided Paine’s first steps in that city where he was to live until 1787 – and where he met, among many other colonial Masons, John Witherspoon, Frederick Rullenberg, Benjamin Rush, David Rittenhouse, William and Thomas Bradford – and, some time later, Henry Laurens, the Lee brothers, General Roberdeau, Robert Norris, Nathaniel Greene (also a Quaker !), Joel Barlow, Thomas Jefferson (whose membership is not proven), and of course George Washington. And who were to become his friends in revolutionary France? Denton, Condorcet, Lafayette, Sieyes, Brissot, Rochefoucauld, Duchatelet, all Masons. And where did he stay after his release from prison in Paris ? First with Nicolas de Bonneville and then with James Monroe, both of them known as notorious Freemasons.

Paine’s interest in Freemasonry was such that toward the end of his life, in 1805, he wrote a lengthy piece entitled An Essay on the Origins of Freemasonry in which he traces back the birth of Masonry to the ancient rituals of druidism.

But this does not prove, any more than any other detail or fact that we know of, that Paine was a Mason. There is indeed no formal trace of his initiation or membership in England, none in America, and none in France. Questioned about Paine’s membership – questioned because non-Masonic scholars cannot have direct access to English Masonic archives -, the United Grand Lodge of England had only this to answer : “In the absence of any record of his initiation it must, therefore, be assumed that he was not a member of the order’. Whether or not he was initiated, it is most unlikely that Paine ever became a member of a British lodge, if only because English Freemasonry was at that time closely connected with aristocracy and even with the king or his entourage : thus the Duke of Cumberland, Grand Master of the United Grand Lodge until 1790, was succeeded by the future George IV!

In France, although Philippe-Egalite and the future Charles X were also Freemasons, the situation was somewhat different. French lodges (and Paris had no less than 81 lodges) seam to have been socially and politically sore open. During the Revolution the French capital even had an ‘American Lodge” ( known as “la loge des Amerlcains”) which numbered no less than 143 members – but in whose records Paine’s name never appears. Nor does it appear on any of the lists recently established by Alain Le Bihan regarding the respective memberships of ‘le Grand Orient’ and “la Grande Loge de France”.

And yet Bernard Fay maintains that Paine was a Mason. And so do Dr. Robinet in his “Danton emigre” and Franck Alengry in his biography of Concorcet, And Brissot himself alluding in his “Memoirs” to his ‘friend Bonneville and Thomas Payne … who pride themselves on possessing every single secret of the Order*. But Brissot’s remark is no proof: studying the secrets of Freemasonry, or even “possessing” them or some of them, does not necessarily imply that one is a member (I am not a member). In such the same way, Ignace Guillotin, the humanitarian inventor of the guillotine, recorded in his diary that be ‘attended Lodge in company with Mr. Jefferson and Mr.. Paine from the American states’. But this again is no proof, for there were, and there still are today, two types of Masonic meetings: some open to non-members and others tiled (i.e. with the tiler or warden, standing outside the outer door to keep off “cowans” (uninitiated people and eavesdroppers and other unauthorized persons).

More convincing perhaps is the testimony provided by R. Le Porestier in his famous book on the Bavarian Illuminati, a subversive secret society founded in 1778 at Ingoldstadt by an enlightened and ambitious eccentric called Adam Veishaupt. Le Forestier writes that in 1794 (at a time when Thomas Paine was a member of the Convention in Paris), Count Lebrbacb, imperial ambassador in Munich, sent to Vienna a list of illustrious Illuminati containing, among others, the names of the “Duke of Orleans, Becker, La Fayette, Barnave, Brissot, La Rochefoucauld, Mirabeau, Payne, Fauchet, for Prance”. This is indeed an official document, but It is not the record of a specific Masonic Lodge and besides one could actually belong to the Illuminati without necessarily being a Mason. So, again, we are left with no satisfactory evidence.

My investigations in the United States have not been more successful. The name “Thomas Paine’ does figure on several Masonic rosters of the Revolutionary period (in Boston, Albany or Providence), but there is no evidence whatsoever that the man thus listed was the historic figure whose memory we are celebrating today. Similarly local records do mention the creation in 1792 of a Paine’s Lodge E’27” at Amenia, N.Y., but at the time it was not uncommon for lodges to take the name of such or such famous man who had never been initiated. In 180, when Paine died, the Grand Lodges of both Louisiana and Georgia honoured his memory with solemn orations, while the Grand Lodge of South Carolina organized a mourning procession in the streets. but who was actually honoured in these celebrations: the hypothetical Freemason? Or the apostle of Reason? Or the champion of the rights of man? We cannot validly decide.

If we are to understand Paine’s intellectual itinerary, it is quite enough to know that, though he probably never belonged to any specific fraternity, but nevertheless actively sympathized with the Masonic movement and the philosophy it carried. Masonic thought had such in common with his own deistic outlook and his own cult of reason, and it was part of the great intellectual swirl of the age of Enlightenment wherefrom he derived most of his creeds as a rationalist. Therefore it was into ideas rather than into rituals that Franklin initiated his protege, inasmuch as he initiated him into anything. Paine’s psychology is here more convincing than material evidence. A rugged individualist, Paine neither liked collective ceremonies nor secret practices ; he dreamt, instead, of an open form of democracy, of a see-through republic with a public life as transparent as a palace of glass. Both his nature and the lessons of experience made him loathe the idea of regimentation. He never was a declared member of any party or erect or church and It is highly probable that he never joined the Masonic order. “My own mind is my own church”: no words could describe, better than this key sentence of a man who could at best become a “fellow traveler”, as we say today, but whose real vocation was to espouse causes, not structures.

Why then bother, some might rightfully ask, about Paine’s relationship with an organization in which with all probability he never belonged? Well, just as penicillin was invented by a scientist who was in fact looking for something else, so studying Paine in that context – i.e. against the background of Masonic organization and militancy – Inevitably led me to widen the scope of my research – and of my inconclusive findings – to the role of Freemasonry in the American revolution at large. And the paradox is that, although I did not find much about Paine in terms of positive data, I discovered about the larger issue quite a number of interesting things that had hitherto been overly and unjustly neglected. Let me then lift for you at least one tiny corner of the veil.

While non-Masonic historians have, with very few exceptions, tended to overlook the underground role of lodges in the American revolution, the great majority of Masonic scholars have on the contrary been prone to overrate their real impact. One has, therefore, to be even more careful when dealing with so-called secret societies than when studying public data or duly archived history. Consider, for instance, the Declaration of Independence and its 56 signers : how many of them have been identified as Masons? The answer varies considerably from one enumerator to another. William Grimshaw gives a list of 51 Masonic signers, as against 8 only In Henry Coil’s Masonic Encyclopedia. William Boyden suggests 29; Ronald Heaton 9; Philip Roth 20; and the George Washington Masonic National Memorial Library says 30.

The main problem here lies in fact with the unreliability of primary sources. The early lodges and Provincial Grand Lodges were careless about the keeping of records and minutes. In Colonial days, many lodges functioned for a short time only, leaving no trace whatsoever of their transient existence. And during the War of Independence there were many so-called ‘Army Lodges”, which conferred degrees, but kept no records or destroyed them for lack of a safe and steady place to store them in. Over the years a fair amount of Masonic records were destroyed as a result of warfare, or were lost by fire, or discarded by heedless holders through ignorance of their value, or done away with to prevent disclosure. On the whole, what characterizes the surviving vestiges of Masonic life in XVIlIth and early XIXth century America is that they are, more often than not, “gappy”, or fragmentary, or confused, or all three.

Finding relevant Masonic documents is, then, hardly an easy task. Interpreting the any prove to be a risky venture, as is evidenced by the following anecdote. In his fairly reliable listing of “10,000 Famous Freemasons”, William Denslow surprisingly identifies James Madison as a Mason, on the basis of a letter sent to him on February 11, 1795, by John Francis Mercer, governor of Maryland. The passage quoted by Denslow reads : “I have had no opportunity of congratulating you on becoming a Free Mason – a very ancient and honourable fraternity”. If this was no proof, I thought to myself, what could be? Some time later, however, I was able to read Mercer’s letter in its entirety, and found to my astonishment that his hint at Masonry was a mere Joke, a play on words, a metaphor ; that in fact Mercer was congratulating Madison on his recent marriage ; that the ‘fair prophetess who has converted you to the true faith” was no other than his wife, Dolley Payne Todd ; and that the initiation into Masonry to which Mercer referred was nothing but an Initiation into the bonds and mysteries of married life. Although an obvious source of error, this Masonic metaphor is nevertheless interesting and significant In that it shows how important Freemasonry was in the mental world of XVIIIth century Americans.

Freemasonry settled down in British America as early as 1710, four years before Benjamin Franklin printed Anderson’s “Constitutions” known as ‘the Bible of the Masonic Order’ originally published in London in 1723 -, it was only during the decade preceding the Revolution, and during the Revolution itself, that American Freemasonry thrived and grew in a spectacular way. Was there a relation of cause and effect between the two phenomena? That is precisely the question to which I would like to address myself tonight, without of course going into too much detail.

Here are some figures and a selection of events, some well-known, some less known, but the bulk of which is fairly impressive:

Prior to the Revolution, there were more than 100 stationary lodges in the Colonies and upward of 50 travelling military lodges. During the Revolution about 25 additional military lodges were created (10 in the Continental army and 15 in the British ranks). The city of Boston had 6 lodges prior to the Revolution, and 10 lodges had been warranted in Philadelphia when the first Continental Congress met in 1774. The Masonic population of Philadelphia and the vicinity at the time is estimated to have been upward of 1,000, 14. about 3% of the total population, as against 2.5% in Boston. It has also been calculated that there were some 3,000 Freemasons in the thirteen United States. In 1790 for a total population of 4 million, i.e. almost 1%.

Freemasons were present and active in the very first stages of the rebellion. It was James Otis, a member of St John’s Lodge In Boston, who in 1761 first took the now familiar view that taxation without representation is tyranny. In 1772 the burning of the HMS Gaspee was organized and led by Abraham Whipple of St John’s Lodge in Providence. The leaders of the Committees of Correspondence, created that very same year, were most often Freemasons, as is shown by the records. And there is such reason to believe that the Boston Tea Party was headed and carried out by Bostonian Freemasons, although only nine of them actually took part in the attack on the tea vessels. The fact that the chief ringleader, Samuel Adams, was probably not a Mason did not deter Paul Revere, future Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of Massachusetts, from declaring the very next day : “The Tea Party was as dignified a Masonic event as the laying of a cornerstone, as indeed in very truth it was”.

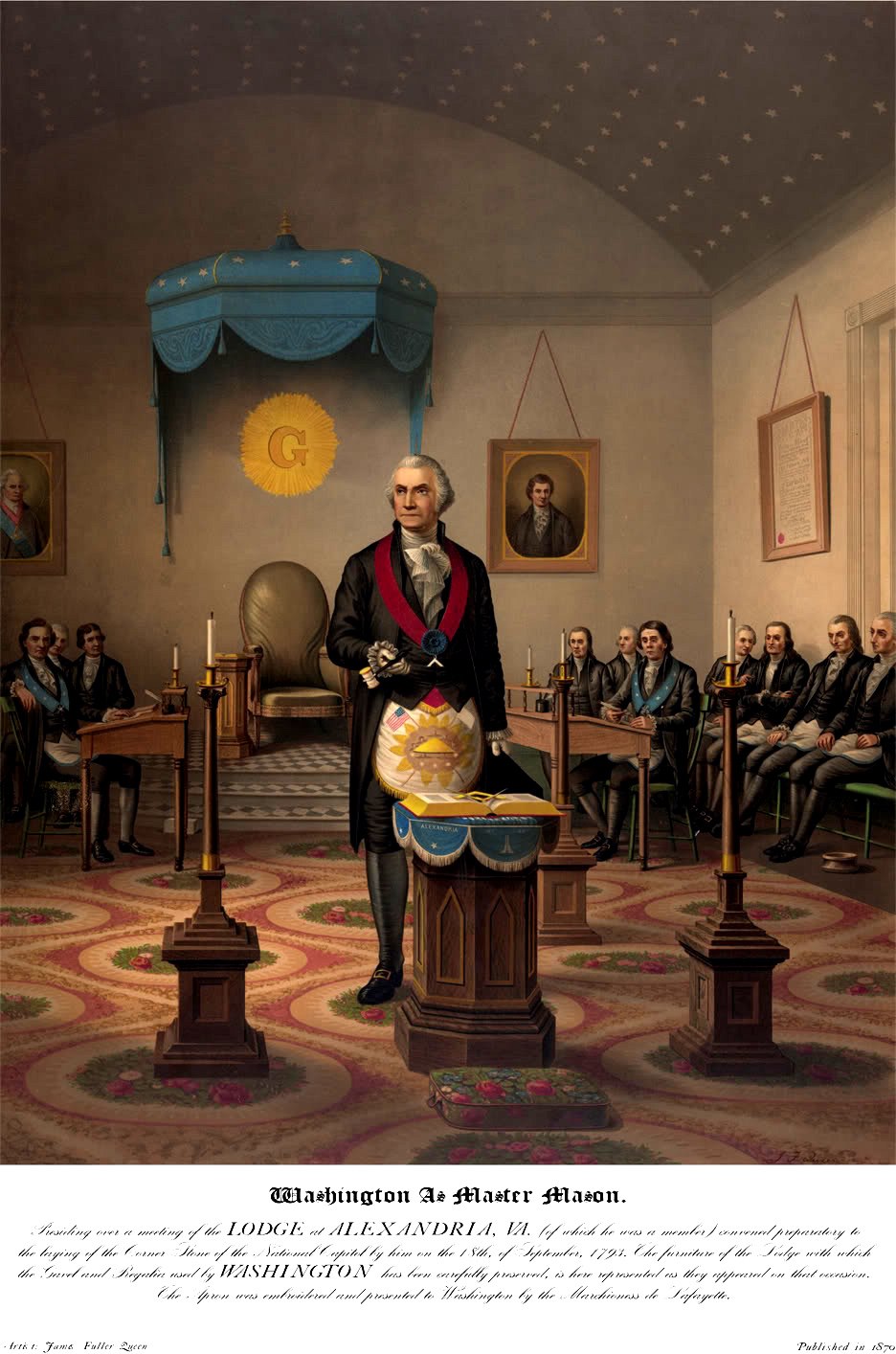

I have already mentioned the high proportion of Masonic signers of the Declaration of Independence. According to the best available sources, between one third and two thirds of the 39 signers of the Constitution were also Masons. In that connection, an original way of looking at the Constitutional Convention would be to view it as a meeting to a large extent organized according to Masonic rule, i.e. behind locked doors, with the proceedings held in camera, and George Washington himself elected to the chair – let alone certain similarities between the historic Federal document and Anderson’s Constitution. Be that as it may, the fact of the matter is that many, if not most, of the leading figures of the Revolution belonged to the Masonic Order – or to the ‘Craft’, as it was then called. Such, in addition to those already cited, was the case of: George Washington, John Hancock, Peyton and Edmund Randolph, Henry Laurens, John Dickinson, Robert R. Livingston, John Paul Jones, Robert Treat Paine, Roger Sherman, William Hooper, John Marshall and, in all likelihood, Patrick Henry, John Jay, Richard Henry Lee, Robert Morris, Benjamin Rush, John Witherspoon, David Rittenhouse, etc.

Of the 75 General Officers of the Continental Army, at least 33, and possibly 40 more, were Masons. According to Lafayette, Vashington was always reluctant to appoint a general that was not a member of the Fraternity ; and when be heard that Benedict Arnold had betrayed the American cause, he turned to Henry Knox and Lafayette, both of them Masons, and said in words that have become famous : ‘Thom can we trust now r Montgomery, Greene, Sullivan, Veyne, Clinton, Persons De Kalb, etc. were all “brethren of the Mystic Tie’, as also were Ethan Allen, the Ticonderoga hero, and George Rogers Clark, the conqueror of the Northwest. Quite unsurprisingly, the main protagonists at Yorktown were all Masons : Washington, de Graeae, Rochambeau, d’Estaing, Lincoln, Knox, Hamilton (?), Lafayette, – and Cornwallis himself !

Not all Masons, or Masonic leaders. were Patriots. There were some Loyalist lodges, and Masonry as a whole was not left untouched by what was then known as ‘Toryism’. It seems nevertheless that in most cases political dissensions within the lodges, or between lodges, did not prevent Masons of all persuasions from remaining on speaking. or even brotherly, terms – presumably because, and in the name of their common principles.

I could go on and on with facts, but it is now time to try and account for this profusion of data and its historical significance. That Freemasonry was real is beyond doubt, but the question is : How real and how specific was its actual impact on the American Revolution?

The reality of revolution is so complex that it would be an error to study Freemasonry as an isolated agent of change. Masonic lodges were part of a larger intellectual, institutional, and international phenomenon. They contributed no, or very few, original ideas to the Age of Enlightenment whose ready-made philosophy catered to all their needs. It would be of little use then, to analyze the Masonic discourse at the time because, as we shall see, the medium was in that instance the message, and it was through rites and social behaviour that Masonic ideology was in fact produced. From an institutional point of view, lodges were one particular form amid a proliferation of clubs, salons, literary circles, reading associations, learned societies, scientific or philosophical academies – what we in French call “socillites de pauses” : Franklin’s “Junto”, or the Philosophical Society, or the first Anti-Slavery Association in Philadelphia are well-known instances of this. In terms of social change, some of these active cells were more significant than others, and R.R. Palmer, author of The Age of the Democratic Revolution, was, I think, mistaken when he suggested that “reading clubs were more important than Freemasonry as nurseries of pro-Revolutionary feeling’. At the time, instilling new attitudes was probably more subversive than propagating theories and doctrines. Palmer makes a good point, though, when he explains that the network of Masonry created across the Atlantic “an international and interclass sense of fellowship among men fired by ideas of liberty, progress, and reform”. The Masonic ties between France and America were particularly strong, and the fact that Washington and most American leaders were Masons should not be neglected. On his arrival In Paris in 1777, one of the first things Franklin did to popularize the Revolution was to Join the Lodge of the Wine Sisters; and, with perhaps the exception of Jefferson and Silas Deane, all of the American negotiators in Paris were Masons, as were most of their French counterparts. In those years common membership of the Craft worked, among these Republicans and Royalists of two different countries, as a kind of political esperanto a higher language also understood and spoken in England by such illustrious Masons as Burke or Chatham or Wilkes.

But the Masonic “International” was, at the very most, an intellectual network, a shared language, a common mold ; by no means the instrument of some wilful conspiracy. Historically, the “plot theory” was formulated alter the event, at the very end of the 1790’s, and was nothing but an unsupported piece of counter-revolutionary polemic. The doctrine of an underground machination against ‘the Throne and the Altar” was originally put forward by Barruel in France and John Robison in Britain. Robison’s ideas were peddled in America by leading figures of the New England Congregationalist establishment like Jedidiah Morse, minister at Charlestown, David Tappan, professor of divinity at Harvard, and Timothy Dwight, president of Tale, not only were Masons accused of subverting social order and religion, but it was also proclaimed that they were manipulated by infiltrated agents, and that their own conspiracy was in fact secretly engineered by the international Order of the Bavarian Illuminati. Thomas Paine, who was then living in Paris, was one of Morse’s favourite targets. His widely-circulated pamphlets being viewed as “part of the general plan to accomplish universal demoralization”. Theodore Dwight, brother to Timothy, aimed even higher : “if I were to make proselytes to illumination in the United States, he wrote on Independence Day 1798, I should in the first place apply to Thomas Jefferson, Albert Gallatin, and their political associates”. Uttered at the end of the century, these political attacks sounded like rearguard actions, but at the same time, with the myth of Masonic conspiracy serving as a pretext, they actually foreshadowed, and paved the way for, the anti-Masonic witch-hunt of the early 1830s.

When one considers Freemasonry during the Revolutionary period, the difficult thing in to weigh the active, conscious, militant part it played, against its more seminal role in favour of independence, human rights, or the republic : a rule and an influence that extended tar beyond the bounds of the Craft Itself and which, in spite of its diffuseness, or perhaps thanks to It, was an important factor of ideological and political transformation. Whether the political commitment of a Patriot should be ascribed to his being a Mason or to some other cause can hardly ever be proved. But what it did to an American to ‘attend lodge” and model his behaviour on its rituals is something whose impact can more easily be grasped and measured.

In all lodges, whatever their affiliation, an extensive though orderly and ritualized liberty of expression and discussion was the rule – much on the model of British Parliament -, together with a common practice of tolerance and open-mindedness. Therefore what American Masonry actually contributed to the Revolutionary movement was first and foremost an Image of its own functioning, with its local cells operating as discreet schools of liberalism, as republics in miniature, as living laboratories of democratic and egalitarian values, as the palpable prefiguration of a new era. Belonging to a lodge was in itself a form of dissent, since the lodge worked, both in vitro and in vivo as a social utopia experimented against a background of universal tyranny.

While attending lodge, Colonial Masons normally divested themselves of their social differences so as to appear, if only for a limited time, on an equal footing with their brethren. An artificial form of equality was thus pitted against the social hierarchies of the outside world, with its oppressive pattern of age-old subordinators. To be a Mason was to usher in “a world turned upside down” and, as Francois Furet has pointed out, a Masonic lodge was, a societie pensee, “characterized, for each of its members, by nothing but its relation to Ideas, thereby heralding the functioning of democracy”. If Masonry was important in the American Revolution it was not as the instrument of a mythical plot, but because, Furet goes on to say it embodied more than anything else, “the chemistry of the new power, with the social becoming political, and opinion turned into action”. By and large, Masons tended to belong to social groups that were not miles apart, so that their abstract equality within lodges was not too difficult to achieve ; but what mattered politically and ideologically was the ritual itself as the living sign of a better world for all. And since 1% of all Americans belonged to the Craft, it may be inferred that the Revolutionary impact of Masonry was by no means insignificant. Although they debated new and sometimes subversive ideas, Masonic lodges were not regarded as dangerous institutions and no authority ever thought of banning them, at least during the Revolutionary period. What went then unnoticed was that Masons were, so to say, political mutants, with their lodges working in the dark as unseen vehicles of social change. Thomas Paine was not wrong in emphasizing the role of pre-revolutionary ideas and the force of the mind – ‘by which revolutions are generated’ ; but be missed the central point, which is to know how these ideas worked their way into society and gradually settled there as new dynamic forms of social practice.

American Freemasonry was in many ways similar to its European equivalents, but it had features of its own that should not be overlooked.

Especially when contrasted with French Masonry, the American Craft of the time was original in that it never defined itself, and never was, anti-religious. Henry May has shown that Enlightenment figures in America were much less committed to rationalism and freethinking, much less cut off from religious traditions than their European counterparts. A parallel distinction should be made with regard to Masonry: religious tolerance, not to say ecumenical attitudes, was a striking feature of American lodges, although Deism, with its view of God as the great architect of the universe, fitted more neatly into the spiritual pattern of Masonry. One had to be a believer to become a Mason, and the Bible was used in all Masonic rituals. In America no Mason, however committed to republican ideas, ever dreamt of establishing a Civil Constitution of the Clergy, not to mention the enthronement of a Supreme Being as a substitute for the Christian god! The anti-religious excesses of the French Revolution had, to say the least, a cooling effect and many sympathized with Mason in America – and, to begin with, on George Washington himself.

During the whole Revolutionary period, American lodges also worked as centers of welcome and social integration for immigrants newly-arrived from Europe, for foreign soldiers serving in the Continental Army, and later on for French expatriates who were hounded out of their country by the Terror. Aliens were readily admitted into American lodges, and several foreign lodges came into being during the war. The first French lodge known as ‘la loge de A’mitie’, was created. In Boston as early as 1779. It soon got into trouble, however, as a result of financial misappropriations and, some time after, because its Right Worshipful Master was deservedly accused of bigamy : the ways of social integration are unfathomable! For native Americans, Masonic lodges seem in many cases to have served as places of transit from social life to patriotic or political action. This may well have been the case for George Washington, Initiated as a mere land-surveyor at the early age of 20, and for Franklin as well, who was made a Mason when he was 25.

I don’t have time to tell you about the anti-Masonic hysteria of the late 1820’s, but, to put the whole matter in a nut shell, I will simply say that, as long as the American Masonic Order was part and parcel of Colonial Society, as as long as it surfed, as it were, over the Revolutionary wave, or even guided it. It was not seriously challenged ; problems emerged several decades later when it shrank back into a separate brotherhood, seemingly cut off from the larger fraternity of the new nation.

Nor do I have time to tell you about the birth In 1775, and subsequent development, of a Black Masonic Fraternity called ‘Prince Hall Freemasonry” after the name of its founder. Even today, with its 5,000 lodges and 300,000 members, this American Negro Craft is still looked upon as “spurious, Irregular, and clandestine” by all its caucasian counterparts in the United States. Prince Hall Freemasonry had no direct impact on the American Revolution, but it was ironically during the Revolution, and in its context, that racial discrimination became a bone of contention between men whose raison d’être, as either white or black Masons, was a brotherhood.

I discovered all these things, and many more, thanks to Thomas Paine and the riddle of his relationship with the Masonic Order. Paine was not a Mason, but like all the American, British or French Masons with whom be used to mix, he was a builder; the builder of a democratic system or Ideal based on freedom, equality, social solidarity, and brotherhood. He is usually bailed in the United States as one of the Founding Fathers. Perhaps it would be more appropriate, especially today, especially here, to celebrate him as a “Founding Brother”.