By Edmund and Ruth Frow

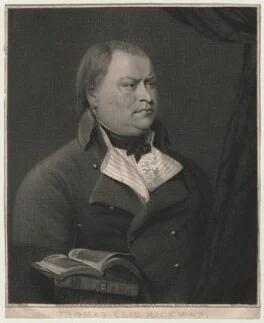

Thomas “Clio” Rickman, who was dubbed an eccentric in one journal, at an early age was accorded the title, “Clio” by his literary friends in Lewes. Many of his youthful effusions were signed “Clio” and he subsequently used it as one of his names.

Rickman was a classical scholar who had travelled widely. He was given the accolade of “Citizen of the World” for “having made truth the object of his discovery, and man that of his affection, sees the vices and errors of every country, and loves virtue in all.” Thomas Rickman was born into a Quaker family at Cliff, near Lewes, on 27th. July, 1761. He was the son of John Rickman (c.1715-1789) and Elizabeth nee Peter. He was educated at the public school at Coggenhall in Essex, where he studied the dead languages but stole away to read the more congenial Telemachus and Homer.

His literary talent blossomed early and at the age of ten he sent his first essay to the Monthly Ledger. At thirteen he was apprenticed to his uncle, a surgeon in Maidenhead, where he remained for five years. During this time he read extensively, Bolingbroke, Hulme, Shaftsbury, Voltaire, Rousseau and Helveticus. He continued to write both prose and poetry for periodic publications.

While in Maidenhead he met and married Miss Maria Emlyn of Windsor, the third daughter of an architect. Sadly she died after only eleven months of marriage in 1784. Grief stricken, Rickman returned to Lewes to join his father and brother in a mercantile business. He left the Quakers although he had only been a nominal member. Unable to settle, he went to London where he led a restless life. He then went to Holland and Catalonia in Spain.

On his return to London in 1785, he set up in business as a printer and bookseller, first at 39, Leadenhall Street, then at 7, Upper Marylebone Street, “where all Periodical Publications are regularly served, and Newspapers franked to any part of England – Copper plates elegantly engraved – Printing and Bookbinding done in the best manner – an extensive Circulating Library.” He wrote and published, A Fallen Cottage, the list of subscribers testifying to the wide support for his work.

In 1792, Rickman met Thomas Paine with whom he had frequently corresponded. They soon became firm friends and Paine benefited from Rickman’s knowledge of languages and classical education. Paine lived with Rickman and his second wife and whilst there he completed the second part of Rights of Man. On the small table on which it was written, Rickman later affixed a plaque with a commemorative inscription. This is now in the National Museum of Labour History.

Rickman and Paine joined The Society for Constitutional Information which, after reaching a low ebb, had been revived. Rickman’s membership of the society was proposed by Paine and seconded by Home Tooke on June 22nd. 1792. He was formally elected on the 29th (Minute Book S.C.1 T.S.11/962, 103r, 115r, 91r, 93r). It met at the Crown and Anchor tavern and members included Lord Dare, Sir James Mackintosh, Home Tooke, Thomas Holcroft, William Sharp, the engraver, Joseph Gerald, John Richter, the publisher and Capt.Perry, publisher of The Argus. Rickman describes friends that he shared with Paine. They moved in radical circles with Joel Barlow, Mary Wollstonecraft and Joseph Priestly, among others (Rickman. Life of Paine. pp.100-1).

The government, anxious to keep an eye on Paine, sent a spy, Charles Ross, to watch the activities in Rickman’s house. Paine, already awaiting trial, was alerted to the danger he was in and fled to France. Two Bills were found against Rickman, for publishing the second part of Rights of Man and The Letter to the Addressers. To avoid imprisonment, Rickman joined Paine in France and did not appear publicly in England for two years. His life in France is described in detail in his Life of Paine (pp.123-169).

In 1794, Rickman returned and resumed his work in London. His wife had kept the business going in extremely difficult circumstances.

When the Corresponding Society sent two delegates, Maurice Margarot and Joseph Gerrald to assist the reformers at their convention in Edinburgh, the authorities arrested them, and after a mockery of a trial, sentenced them to fourteen years transportation. Rickman did not forget Margarot and in 1814 wrote a tribute to him called “Elegiac Lines to the Memory of Maurice Margarot”:

Thus, thus have fared the BEST in every clime,

Witness the records of revolving time;

And such, intrepid MARGAROT, they fate,

The victim of a blind misguided state

The friend of JUSTICE and of TRUTH you stood,

Hurling defiance to Oppression’s clan,

And nobly labouring for the RIGHTS OF MAN!

Worse followed. The passing of the Two Acts at the end of 1795 prohibited seditious assemblies and made it a treasonable offence to incite to hatred or contempt of the king or the constitution or government by speech or in writing.

Many reformers fled to America. Others, like Thelwall, left London. But Rickman found ways of using the limited legal scope available, avoiding imprisonment by slipping across to France when things became too hot. He continued to write and publish and in 1800 he hit back at the government in a poem, Mr. Pitt’s Democracy Manifest. In 1801, the authorities tightened security and checked Rickman’s overseas mail.

In 1802, Rickman crossed the Channel and spent a week with Paine at Havre to help his friend prepare for his journey to America. On his return to London, he suffered a major tragedy and lost his desk containing three thousand original manuscripts.

In 1803 he wrote and published An Ode to the Emancipation of the Blacks in San Domingo.

In 1804 he published a few copies of a pamphlet for his friends. It was entitled, Thomas Paine to the People of England on the Invasion of England in 1804. The authorities managed to trap Rickman, sending a policeman in disguise to his shop and he was given a parcel of the pamphlets for delivery to Eastburn in Leeds. Rickman was arrested and his books and papers seized. Although the Attorney General dropped the prosecution after nine months, Rickman and his family suffered considerably. By then Mrs.Rickman had presented her husband with seven children, the boys having been blessed with the names Paine, Washington, Franklin, Rousseau, Pentarch and Volney. The seventh was probably a girl and her name is not recorded.

Rickman did not let the situation pass without retaliation. He published a poem on “Corruption” which had an extensive sale as a broadsheet.

When dire Corruption devastates the land

And Whigs and Tories (each a factious band)

When slaves of pow’r each cursed plan pursue,

The Rights of Man and Nature to subdue;

When gaunt oppression fearless holds her course,

And Vile Hypocrisy is leagued with force,

Each energy and feeling to destroy,

That gives man comfort, every joy;

Banish Corruption from our once blessed shore,

And wield the scourge of tyranny no more.

Be to the People faithful, firm, and true

And such will ever be their conduct toward you.

Rickman was always ready to respond to current events. In 1806 when William Pitt died, he wrote:

Reader! with eye indignant view this bier;

The foe of all the human race lies here.

With talents small, and those directed, too,

Virtue and truth and wisdom to subdue,

He lived to every noble motive blind,

And died, the execration of mankind.

When Thomas Paine died in 1809, he left Rickman a legacy of half the proceeds from the sale of North Farm.

In 1818 Rickman and a few other friends of Paine, induced Richard Carlile to issue a cheap edition of The Age of Reason. This had not been sold legally in Britain since 1797. The following year, Rickman published his Life of Thomas Paine, an impressionist account. This led to controversy with W.T.Sherman, whose own biography of Paine had appeared in July 1819. Sherwin relied largely on correspondence between Paine and his many friends and acquaintances.

By 1820, Rickman was in reduced circumstances and ill. He was forced to sell his house in Carnaby Street. So difficult were his circumstances that Francis Place sent him a gift of £3 in March, 1832. Rickman died on 15th. of February, 1834, aged 74, and was buried at the Friend’s Burial Ground at Bunhill Fields.

Rickman was one of Thomas Paine’s closest friends. He wrote one of the first sympathetic biographies of him. His poetry, usually published under the name of Clio, was ephemeral. He responded to situations as they arose and often composed on journeys or walking or even skating. Well received at first and often set to music and sung in taverns and at radical meetings, they were soon forgotten.

His courage as a publisher and bookseller in the period of the radical reform movement give him a place in history beside Danial Isaac Eaton, Thomas Spence and Richard (Citizen) Lee.