By William Doyle

The Thomas Paine Lecture, University of East Anglia, 1992

The radicalism of Thomas Paine, Englishman, and Thomas Paine, United States Citizen, is well established and recognised. As I look down the list of distinguished previous lecturers in this series and their subjects, I see that both these aspects of his amazing career have been authoritatively discussed and elucidated; and I do not intend, nor am I qualified, to take that discussion further. But it is useful nevertheless at the outset to remind ourselves briefly of Paine’s claim to radicalism in the English-speaking world; because my main purpose today is to establish those claims in the French speaking world, too. Paine established his credentials, you will remember, in 1776 when he advised the American rebels in Common Sense to renounce their allegiance to George III and proclaim themselves an independent republic. By 1778, in the pamphlet series, The Crisis, he was advising the people of Great Britain to get rid of monarchy too. He took this theme up more memorably in Part 2 of Rights of Man, published in the spring of 1792, where monarchy was denounced as “the master-fraud, which shelters all others;” and where he put forward a comprehensive programme, not for reforming the British Constitution, but for giving his native country a constitution for the first time; since he believed that until then all it had was “merely a form of Government without a constitution” – a situation which obtains to this day. His prescriptions were radical indeed: redistributive taxation, an end to primogeniture, old age pensions, subsidised education, and of course a written constitution ensuring fair representation of the sovereign people and strict constraints on the abuse of power. By 1796 he was publicly castigating his old hero, George Washington, for just such abuses of power and monarchical tendencies. And just before that he had thrown down a challenge to Christians of all persuasions with The Age of Reason, that democratic denunciation of theology, revealed religion and those who lived well on the profits of such impostures, – the clergy. Throughout most of these writings the message of Thomas Paine is that there are better ways of conducting human affairs; that they can be achieved if men recognise their own capacities, and their own autonomy; and that, for the first time in human history, a better way has been attempted. It has been attempted in America, the example of which suffuses the Rights of Man as much as if not more than that of France, especially in Part 2; and of course, from 1789 it has been attempted in France, when men seized control of their own destiny, not on the edge of virgin forests, where it was relatively easy to begin afresh, but in the very corrupt heart of old Europe, an “Augean stable of parasites and plunderers too abominably filthy to be cleansed, by anything short of a complete and universal Revolution.” And apart from refuting Burke and his “horrid principles”, the avowed purpose of Rights of Man was to offer an accessibletranslation into English of the founding manifesto of the French Revolution, the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen of August 1798, the destined preamble (as it still was when Part 1 of Paine’s book was published in the spring of 1791) of the new French constitution.

All this is well known. What is perhaps less well known is that when he wrote Part 1 of Rights of Man Paine scarcely knew France. He had spent three months there in 1787. He had spent most of his time there in the company of Americans, or Frenchmen like Lafayette who liked to speak English. And although we have no reason to doubt that the translation of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen is his own, it is well attested that he spoke no French. We all know what a world of difference there is between using and understanding the written, as opposed to the spoken word in a foreign language. Thus it was that when, in January 1793, as a member of the French national Convention, he made his only attempt to address his fellow deputies, he stood mute on the tribune while his speech was read for him. Nor had he, in France in 1787, foreseen the Revolution; much less that it would turn republican. Louis XVI at this time was in fact a king he rather approved of, for had he not come to the aid of the United States in its struggle for independence? Of revolutionary France he knew nothing at first hand until the end of 1789; and the account which he gives in Rights of Man of events there between the fall of the Bastille and the October Days is entirely second-hand, even if the source of his information was no less an observer that Thomas Jefferson. But his first sojourn in regenerated Paris, during the first three months of 1790, was at a time when the Revolution’s initial enthusiasms had not yet turned sour; and when he returned to England to take up cudgels on its behalf, it was this euphoric phase that was his only direct experience of it. By the time he returned once more to Paris, in the spring of 1791, Rights of Man had been published, and he was now the best-known defender in the world of two Revolutions.

By that time, however, the French Revolution had moved on; and the euphoric consensus of twelve months before had not survived. The costs of comprehensive revolution were becoming apparent, and bitter divisions and resentments were beginning to open up and fester, notably over the questions of religion, and of the monarchy. Always suspected but never proven, the king’s hostility to the work of the Revolution was brought to the surface by the religious question in the spring of 1791. As that year opened, all beneficed clergy in France were required to take an oath of loyalty to the Constitution. Those who refused to do so were to lose their benefices. Louis XVI had sanctioned this law, but he knew (as the world was to know some months later) that the Pope disapproved of the oath. Accordingly the king refused to confess to or receive the sacraments from any priest who had taken it. This refusal could not be disguised, so that the spring saw mounting suspicion of the king and his intentions. This atmosphere in turn impelled the king to think of escaping the country; which he finally tried, with disastrous results, on 21 June: the ill-fated flight to Varennes. Paine was in Paris as this storm blew up, and then broke; and as in 1776 his reaction was one of common sense. The king had proved impossible to deal with, so the only solution was a republic.

What was Paine doing in France that spring? He was returning to where the action was; and perhaps keeping prudently out of England until the first storm over his book blew itself out. And the company he kept there was that of his old, English speaking friends. Jefferson had by now returned to America, but Lafayette was very much in the centre of things, as commander of the National Guard. Paine lodged with Condorcet, the last of the philosopher, was on familiar terms with Brissot, a leading journalist and enthusiast for all things American; and was closely associated with one of the leading intellectual centres of early revolutionary Paris, the Cercle Social Now the Cercle Social has long enjoyed a special reputation among historians. Among the men of the left who dominated historiography of the French Revolution for two thirds of this century, the Cercle Social was identified as a centre of progressive thought and radicalism. Karl Marx himself commended it, even if he thought much of its activity utopian. But in its concern for wider democracy and social justice, and the campaign it fought in its famous newspaper, the Bouche de Fer, against the electoral restrictions envisaged by the National Assembly, it was seen as forward-looking and a precursor of the popular values which were to triumph, however briefly, in 1793-4. It proudly proclaimed itself committed to the ideas of the Enlightenment; and particularly those of Rousseau; and it made no secret of the inspiration it derived from Freemasonry. No wonder Paine was drawn into its circle. He was a democrat, he was a fervent disciple of the rational Enlightenment, and indeed a sympathiser with masonic ideals, on which late in life he wrote an essay (as a previous lecture in this series has noted). And when the king fled, members of the Cercle Social were among the first to draw the obvious conclusion that now was the time to get rid of the monarchy entirely and establish a republic. Having Paine among them at this moment seemed providential, and they turned to him, as the world’s best known anti-monarchist, to put their views into words. When some of them formed themselves into a “Society of Republicans” and launched a journal The Republican to propagate their cause, they had Paine write the leading articles and then translated them for him. They asked him, too, to write a republican manifesto which appeared all over Paris on 1 July, a clear attempt to re-enact the triumph of Common Sense in America fifteen years beforehand. But this time it did not work; or at least it did not work in the same way. There is no doubt that French republicanism, which did not exist in 1789, was born in the weeks following the flight to Varennes, and that Paine played a key roll in articulating it. But it was far from a movement that swept the nation overnight, as it had in America. In fact its immediate fate was to be crushed, when republican petitioners were shot down by the Paris National Guard on 17 July in the massacre of the Champ de Mars. It took another year to get rid of Louis XVI, and for a lot of that time republicanism had gone underground. Paine himself returned to England on 13 July, just before the massacre, to write Part II of Rights of Man, and he remained there, in the thick of controversy, for the next 14 months. Thus he played no active and direct part in the final overthrow of the French monarchy on 10 August 1792. But his republican credentials were acknowledged when he was proclaimed a French citizen and, the next month, elected by no less than three departments as a member of the Convention which was to endow France with a republican constitution.

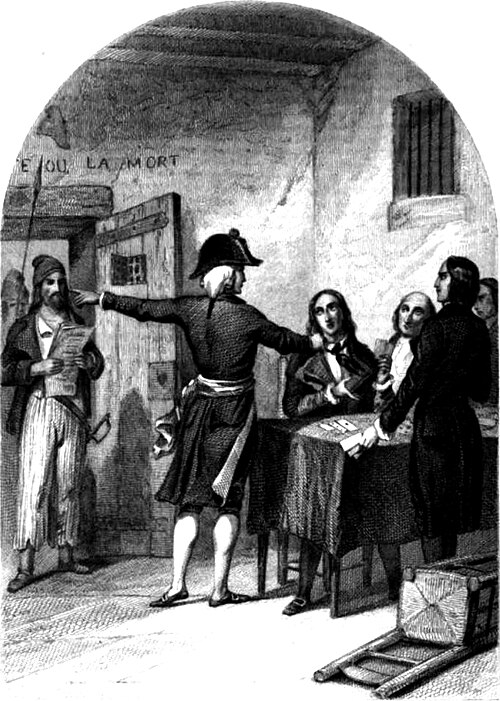

But let me now briefly return to the Cercle Social. It used to be thought that it, and the Bouche de Fer, disappeared forever in the anti-republican repression that followed the Champ de Mars massacre. Historians therefore treated it as a curious but premature forerunner of more serious reform that was to come later; but with no direct connection with the Jacobin Republic of the year II, which was the real, if ill-fated, social and political experiment. Six years ago, however, the American historian Gary Kates devoted the first ever scholarly monograph to the Cercle Social and its history, and what he discovered were a number of remarkable surprises. He was able to show that the group behind the Cercle and the Bouche de Fer did not disperse or cease their activities after July 1791; they simply became less a club than a publishing house. As such, they remained an influential source of radicalism and republicanism. But those they supported and worked with were not, as you might expect, the Jacobins who were to triumph in 1793. The Bouche de Fer was in fact the mouthpiece of those who were to be the Jacobins’ main opponents in 1793, and whom they and the sans-culottes of Paris were to purge from the Convention at the beginning of June that year – the Girondins. People like Brissot, Condorcet, Roland; and of course Paine. Clearly this poses a major problem of interpretation and understanding. How could people who had been so radical in 1791 have become so moderate in 1792 and 3? Historians of the Girondins have always wrestled to some extent with such difficulties, but Kates’ research has made them even more acute. In their early days we now know their leaders were a lot more radical than we thought, so the contrast is even more glaring. And this in turn highlights what has always been something of a problem in the interpretation of Thomas Paine. How was it that the great radical republican, once he was elected to the Convention and became an honorary French citizen, sat and voted with the Girondin moderates and – irony of ironies – even tried to spare Louis XVI’s life? For the famous occasion I mentioned earlier when he had a long speech read to the Convention was in fact during the voting on what penalty to impose on the now convicted king. Paine’s solution was that he should not be executed, but kept in prison until the end of the war, and then banished to the United States, where he should pass the rest of his life learning from the everyday example of a free and republican people what liberty really meant: “There, … far removed from the miseries and crimes of royalty, he may learn, from the constant aspect of public prosperity, that the true system of government consists not in kings, but in fair, equal and honourable representation.”

Paine’s stated grounds for preferring this elaborate form of penalty were twofold. One was, if you like, sentimental: that Louis XVI, though a despot, had been a patron of liberty at the time of the American Revolution, and in helping the Americans to free themselves, had performed “a good, a great action”. The other more principled: Paine was opposed to the death penalty. “This cause”, he declared, “must find its advocates in every corner where enlightened politicians and lovers of humanity exist.” And, in a pointed though in no way rancorous reference to one of the leading advocates of killing the king, he noted that at an earlier stage in the Revolution Robespierre had actually moved, unsuccessfully, the abolition of capital punishment. What Paine is saying here, in effect, is that Robespierre has changed his principles but I have not changed mine. As far as he was concerned, principles were what the Age of Revolution was all about. “I have no personal interest in any of these matters” he said to Danton some months later, just before the downfall of the Girondins, “nor in party disputes. I attend only to general principles.”

But so, it seems to me, did the Girondins. This is surely the key to the difficulties of interpretation thrown up by Kates’ conclusions on the Cercle Social. For too long the Girondins have been depicted as social conservatives whose domination of the Convention had to be broken if the progressive and popular programme of the Jacobins and Sans culottes was to triumph. But in 1972, in what seems to me the most important book ever written about the politics of the Convention, the Australian historian Alison Patrick demonstrated conclusively that those called Girondins were far from the dominant or leading group in the Convention; and she noted, what detached observers ought surely to have remarked on long before, that they were on the losing side in most of the crucial votes. While accepting that none of the groups could be legitimately described, or would have been content to be described, as political parties, she was able to demonstrate clear voting patterns, which could only be made sense of by postulating that it was the Jacobins, not the Girondins, who were running the country in the winter of 1792-3. She also showed that those whose voting patterns could be described as a Jacobin one tended to be older and more politically experienced than their opponents. They were practical men; and they saw that there was a war on, and that it was going badly, and that every effort had to be made to win it, or the Revolution would not survive. That was why the Convention had to co-operate with the sans-culottes, the people of Paris who had overthrown the monarchy. It was true that the sans-culottes had perpetrated the horrifying September massacres a few weeks later, but with the Convention sitting in Paris there was no alternative but to go along with what these people wanted, even if that went against many of the things that the revolution of 1789 had been all about. And so what came about in 1792-4, the period of the so-called Jacobin Republic, was the complete reversal of what the National Assembly had tried to establish in 1789 and 1790. Government was centralised, when the aim of the Revolution of 1789 was decentralisation. Power at the centre was unified, when the aim in 1789 had been a separation of powers. Elections were suspended, when regular accountability had been the initial aspiration. Justice was politicised, when a dream of 89 had been to make it independent. A controlled economy was introduced, when educated opinion had been unanimous that free trade was the natural economic order. I am not saying that the Jacobins necessarily believed in any of this, any more than they believed in some of the more utopian declarations made during their period of power but – significantly – never implemented. What they did believe was that, like it or not, it had to be done. Just as most of them plainly did not believe in the purging of the Convention in June 1793, and agonised for weeks before acquiescing in the forcible removal of elected deputies from the national representation. Their reluctance to see this happen strikes me as perfectly genuine; but in the end they concluded it was necessary in order to remove a major obstacle in the way of saving France and its revolution from destruction.

And what was that obstacle? In a word, Girondin intransigence. The Girondins did not believe that the republic should conduct its affairs according to the desires and dictates of the people of Paris; and they did not believe, either, that the issues could be postponed. That was perhaps the essential difference between them and the Jacobins, a difference between idealists and pragmatists; or if you like, between first principles and forced principles. Because, argued the Girondins (and you can distill this from their innumerable speeches), the Parisian issue goes right to the heart of what the Revolution is all about. If the sans-culottes can dictate to the Convention, they do so by force and intimidation, rather than by law. They have shown in the September massacres what they are prepared to do to their opponents – massacre them in cold blood without trial or any semblance of legality. In 1789, the people of France set out to establish the rule of law and to guarantee the civil rights of all citizens. How can one run the country by taking orders from those who have shown nothing but contempt for those principles? Besides, the Convention is the representative body of the entire Nation, and not just Paris. The deputies of the capital, the core of the Jacobins, number only two dozen, and yet they are trying to force the priorities of their constituents down the throats of the representatives of the rest of the Nation, and not just Paris. The deputies of the capital, the core of the Jacobins, number only two dozen, and yet they are trying to force the priorities of their constituents down the throats of the rest of the Nation, much of which plainly does not want to be dictated to in this way. The power wielded by Paris is an affront to the electoral principle, an attempt to confiscate National sovereignty by a small section of the Nation, and because of that yet another clear contravention of the Revolution’s original principles. It was not even as if the sans-culottes spoke for the whole of Paris. Sensible, educated. enlightened people had gone to ground: the ignorant mob had taken over, the sort of people men of education had always thought should not be entrusted with power, and whom they tried to deprive of the vote in 1790. What would happen if such people got their way was seen in the case of the grain trade, on which the sans-culottes wanted strict controls, just as there had been during most of the old regime. Towards the end the royal ministers had toyed timidly with a freer market, and this was not the least of the reasons why ministers were so unpopular in 1789; but almost unanimously the men elected to the National Assembly in that year believed that the Revolution offered an opportunity to establish an enlightened freedom once and for all – the first unequivocal triumph for free market economics. The sans-culottes wanted to reverse that, and in 1793 they succeeded in doing so by forcing the Convention to decree the law of the Maximum, in the teeth of Girondin opposition initially, and then only finally and fully after they had been purged. In Girondin eyes this was the triumph of sheer ignorance and prejudice over Enlightened principles – again the very antithesis of what the French R.volution was supposed to be. Ever since the days of the Cercle Social the Girondins had made plain their belief that the Revolution was the fruit of the Enlightenment, and an opportunity to put into practice Enlightened principles in a way that would have been impossible under the old order. These opportunities would be lost if the ignorant were allowed to override with their prejudices the benevolent convictions of educated men.

All this, it seems to me, suggests that the conventional label of moderates so often attached to the Girondins is in fact profoundly inappropriate. Moderates make and live by compromises, steer a middle course, avoid extremes. Only the political overlay resulting from generations of left-wing adulation of Jacobin populism as the ancestor of later socialisms, only this has prevented historians from seeing that the moderates, in the sense of the compromisers, the realists, the deal-makers, were the Jacobins. And the real revolutionaries, in the sense of the men who put principles before practicalities, were the Girondins. It was they who were the starry-eyed idealists, who believed that you could not defend the principles of the French Revolution by compromising them; and that if the Rights of Man were a universal code they could only be defended by being observed. Those who had written about them in our own time have all agreed that there was no sense in which they constituted a party, or anything like one, and that, indeed, they often indignantly rejected charges that they were one. But this is entirely what one would expect if they were idealists of the sort I am suggesting. Deputies were not there to pursue prearranged programmes or to make deals. They were there to vote according to their conscience and their principles about the public welfare. The party, if there was one, was the Parisian delegation with its regular block-voting and its outside headquarters at the Jacobin club, its systematic conciliation of the sans-culottes and compromising of the principles of 1789. There mere fact that only something like party organisations makes representative assemblies remotely manageable was of no consequence. What was right would be obvious, and opinion should not need to be dragooned in order that right triumphed.

This faith in the conquering power of true principles is also shown in the Girondins’ attitude to foreign powers. It was they who launched the movement towards war in the Autumn of 1791, not because they wanted the vast generation-long upheaval that resulted, but because they thought the conflict was bound to be short, sharp – and victorious. And that was because the French cause was so self-evidently right that subject peoples groaning to follow the French example would rise up at the approach of French arms and overthrow their despotic rulers; and because the enthusiasm and faith in liberty of the regenerated French Nation would overthrow the paper tiger armies of those same despots.

After initial uncertainties, in the Autumn of 1792 that is exactly what seemed to happen, and it was in these circumstances that Brissot declared that France must set all Europe alight, and that the Girondins induced the Convention to offer French fraternity and help to all nations seeking to recover their liberty. This was certainly no moderate policy; and it so alarmed the supposedly extreme Jacobins that in April 1793 they carried a vote rescinding the fraternity and help decree. They were right, of course. Such an open-ended offer was totally reckless and utopian. But what it is evidence of, once again, is the proposition that I have been arguing, that the true French revolutionaries were not the pragmatic, practical, compromising Jacobins, but the principled, impractical, intransigent Girondins. This conclusion makes their ancestry in the utopian Cercle Social no longer surprising, but on the contrary entirely consistent and to be expected. It also makes them obvious soulmates for Thomas Paine.

At last, then, we come back to the figure who is, as he should be, the real subject of this lecture. But I hope that this lengthy detour about the nature of the Girondins will not seem irrelevant. It ought no longer to seem the least surprising that during his time as a deputy to the Convention he should have been identified as a Girondin. All his previous links with France (with the exception of Lafayette, who had by then defected to the Austrians) were with those who now constituted the Girondin leadership. All his radical, republican instincts were also with men who believed that, even in wartime, the French Nation could be governed in accordance with the rights of man and the rule of law rather than the demands of metropolitan pressure groups and threats of force. The true revolutionaries were those who wanted to make the Revolution and its principles work, rather than postpone their implementation until emergencies were over. If the principles of 1789 were sound, and valid, they should be workable, and proof against transient circumstances. Paine’s writings, too, are steeped in the conviction that rational, radical republicanism works. In Revolutions that aim at positive good, he wrote in Part II of Rights of Man, “Reason and discussion, persuasion and conviction, become the weapons in the contest, and it is only when those are attempted to be suppressed that recourse is had to violence. When men unite in agreeing that a thing is good, could it be obtained … the object is more than half accomplished. What they approve as the end they will promote in the means”.

Now we may say that such an approach to public affairs is impossibly naive and utopian, and doomed to disappointment. In Paine’s case it certainly was. In June 1793 his Girondin friends were expelled from the Convention and arrested; in October, under pressure from their sans-culotte enemies, they were executed; at the end of the year Paine himself was arrested, and remained in prison for nine months, seven of them under real threat of being guillotined. And when he turned to his beloved United States to secure his release, as one of their most eminent citizens, they made no great efforts on his behalf. And although the second-rank Girondins who remained alive were restored, like him, to their seats in the Convention in the Autumn of 1794, and were influential in producing the directorial constitution of the Year III, that attempt to get back to the first principles of 1789 was no more successful than the first revolutionary constitution, and within four years had been overthrown by a military coup, just as Burke had predicted would happen, much to Paine’s scorn, in 1790. Despairing of France, Paine returned in 1802 to America, only to find that his popularity had vanished there too as a result of the anti-Christian polemics of The Age of Reason. At the time of the French Revolution’s bicentenary two years ago, it was fashionable to sneer at the attempt made two hundred years ago to build a new, better, more humane and more rational world. Weighty volumes were written to prove that the whole enterprise was doomed from the start to end in blood, destruction and terror. And as regimes collapsed across Europe the lesson was drawn that the only wise approach is to be practical, and sensible, and to accept things as they are rather than trying to build a better world. Thomas Paine and the Girondins thought otherwise, and though they failed to bring the world of their dreams into being there is a genuine tragic heroism in their naivete, – which the Girondins who were executed carried through to the end, singing the Marseillaise as they went to the guillotine. This was not empty swagger. Between the inertia and absurdities of the old order, and the butchery perpetrated by the practical, reality – facing Jacobins, these true revolutionaries offered not a moderate middle course, but an extreme commitment to the improvement of human affairs by reason, argument and example. We can surely applaud their ambition, and lament their failures, even as we shake our heads at their sad overconfidence that these pure ends could be achieved by means just as pure.