By R.G. Daniels

Standing at the entrance to Lympstone Harbour on the river Exe in Devon was a pillar of red sandstone. It was known as Darling Rock, or, by older inhabitants, as Tom Paine’s Field. The effects of wind, rain and tides have eroded the pillar so that it is now a mound of sandstone hardly visible at high tide. Sheep once grazed on it when it was connected to the Cliff Field above the village.

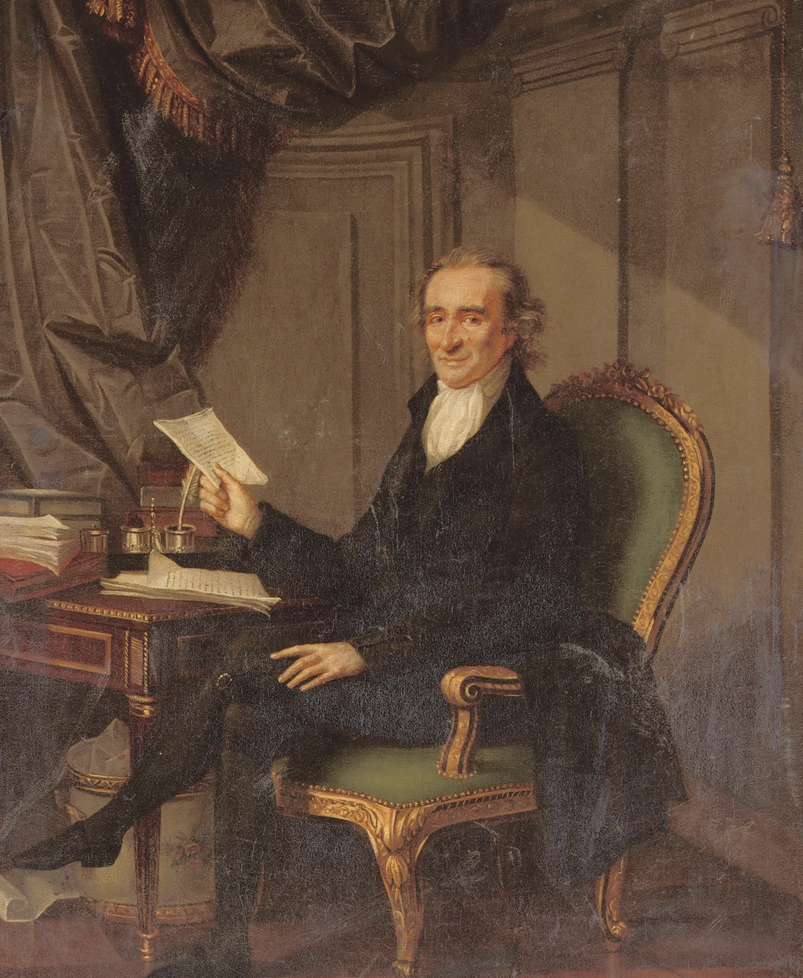

In 1792 the government ordered the public burning of the writings of the ‘notorious pamphleteer Tom Paine’ and, historical tradition has it that this was the site of the local burning.1

On January 3, 1793, Trewman’s Exeter Flying Post2 reported that on the previous Tuesday (January 1), ‘the loyal inhabitants of Exmouth (about two miles south of Lympstone) and its environs assembled for the purpose of hanging and burning Tom Paine. A handsome collection for that purpose having been previously made – about 12 o’clock the procession began, consisting of the trades-people of the town, the farmers of the neighbourhood and sailors, two and two with bands of music, banners flying etc., etc., and lastly an effigy of Tom Paine in a cart, with the Rights of Man in one hand and a pair of stays in the other. They paraded through every part of the town singing God Save the King and receiving from the inhabitants every testimony of loyalty to his Majesty, veneration for the constitution and detestation of the principles of the miscreant they were about to burn. The procession then went to the Point where they hung the effigy on a gibbet 50 feet high, then burnt it amid the acclamations of every individual present.’

Robert Morrell3 has recorded three instances, one near Nottingham, one at Titmarch and another at Thrapstone, both in Northamptonshire, of similar hangings and burnings.

It would appear that then, as now, the public can be easily inflamed and persuaded, against their own good, that their enemies are those whom the government of the day wish them to regard as such.

There must be many other instances of similar happenings throughout England. Readers may like to explore local libraries and historical societies for such reports.

References

- Devonshire Association. Reports and Transactions. 88. 1956. p.110. 8 plates.

- Cann, I.G. & Bush, R.J.E. Extracts from Trewman’s Exeter Flying Post from 1763. Volt. pp.51-52.

- Morrell, R.W. ‘Burning Paine in Effigy. TPS Bulletin.